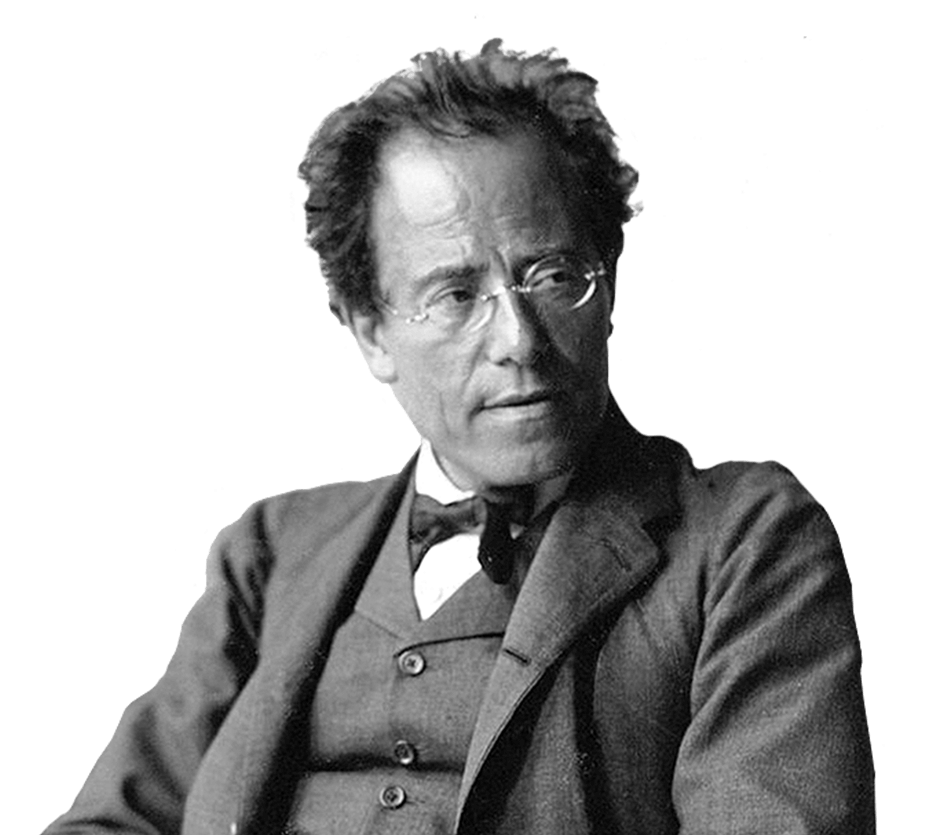

Mahler’s work carries a vision of the modern world, an amazing palette of moods – from tempers passionate and picturesque to bizarre scenes, meditations and confessions of ultimate tenderness.

The total number of performances of compositions by

Gustav Mahler: 217

The three most performed works

| 30 times | Adagio from Symphony No. 10 |

| 27 times | Symphony No. 1 |

| 23 times | Rückert Lieder |

The statistical data compiled, published and shared by Alexander Goldscheider © Citing from his book Jiří Bělohlávek: A Life in Pictures. [ 2 ]

Gustav Mahler’s work followed Jiří Bělohlávek throughout his career. Bělohlávek expressed his interest in the music right from the start, when he chose his Symphony No.4 in G major for his graduation concert in 1972. Although one cannot compare the number of Bělohlávek’s performances of Mahler with those of Dvořák, Janáček or Martinů, he can be rightly counted among “Mahlerian” conductors as his interpretations were highly acclaimed.

Bělohlávek performed Mahler regularly with every orchestra where he was the chief or permanent conductor. Already his 1975 interpretation of Symphony No.1 in D major with the State Philharmonic Orchestra in Brno convinced everyone that Bělohlávek and Mahler got on very well. The music critic Petr Vít appreciated his original interpretation and the fact that “the conductor aimed at contrasting and precisely elaborated sections in which every resounding detail was subordinated to a consciously built up and cohesive whole of magnificent and musically voiced Mahlerian fresco of strong dynamic and dramatic effect.” [ 3 ]

Bělohlávek conducted the Brno Philharmonic in Mahler’s Symphony No.4 in G major in January 1977, and Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen in December. When guest conducting the Brno orchestra in the 1990s, he brought Mahler again. In September 1994, they together performed Symphony No.2 in C minor, with Eva Urbanová and Eleonora Wen as the vocal soloists and the Czech Philharmonic Choir of Brno. When reviewing the concert, professor Rudolf Pečman wrote: “The audience were following the artists and orchestra as if in trance. The choir, the soloists and the orchestra led by Jiří Bělohlávek literally seized Mahler’s music. The conductor, who is a true Mahlerian expert, prepared moments of absolute artistic ecstasy. The audience thanked in the form of intensive, and here unprecedented, ovation. Mahler’s music sounded like a massive flow springing directly from the composer’s heart, and it overwhelmed the hearts of those present.” [ 4 ]

During the long period when Bělohlávek was the chief conductor of the Prague Symphony Orchestra, Mahler was featured regularly in the repertoire, too. They performed almost all of Mahler’s symphonies, justly receiving praise from both Czech and international critics. Next to Dvořák and Smetana, Mahler became therefore a first-class export item requested of the orchestra and the conductor by agencies abroad. They triumphed with Mahler in 1980 at the Montreux Festival in Switzerland and in 1989 in Leipzig.

Jiří Bělohlávek created a lively and therefore a semantically infinitely rich musical entity full of admirable architectonic order. He interpreted the Second Symphony with respect for detail and the precision of their preparation was tangible, at the same time an immense musical monument was spread in front of us, with a number of partial climaxes and periods of tranquillity, all building up to the final ideological outcome of the whole work. (…) The reaction of the Leipzig audience was the nicest reward for the Prague Symphony Orchestra, both choirs, soloists and the conductor. And it became clear that in Jiří Bělohlávek we have a conductor who is going to carry on our tradition of Mahlerian interpretation. He brought the Second Symphony to our northern neighbours in a perfect export quality.

… the concert of the Prague Symphony Orchestra was a major musical experience. From the very first bars of Mahler’s First Symphony “Titan”, the conductor Jiří Bělohlávek led us into the centre of “beauty”. This work by the master of exulting musical connections and the genius of bright colours was conducted by the ensemble’s chief conductor in an engrossing and astonishing manner – from the first to the last bar. I could go on adding more and more superlatives. This concert will stay in the memories of the audience as one of the most beautiful moments of the 1980 festival.

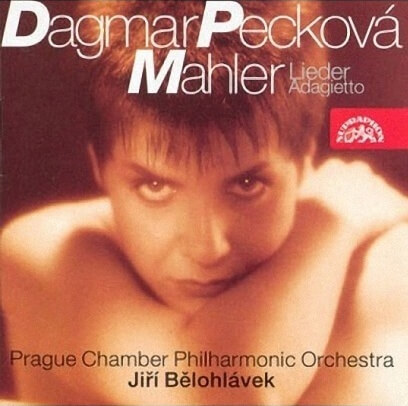

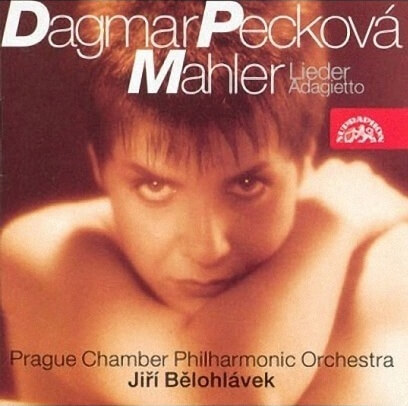

Bělohlávek performed not only Mahler’s symphonies but also his song cycles. When working with the PKF – Prague Philharmonia, he recorded some of them together with Dagmar Pecková. A Supraphon album entitled “Dagmar Pecková. Lieder. Adagietto” was made in 1996, containing Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, Kindertotenlieder and the Rückert Lieder. The songs were complemented by Adagietto from Symphony No.5. A second recording of Mahler was released on the same label in the same year entitled “Mahler, Berio – Dagmar Pecková” which, next to Berio’s music, presented Mahler’s Five Early Songs, Des Knaben Wunderhorn and the fourth movement from Symphony No.2 in C minor - Urlicht. Sehr feierlich, aber schlicht.

These recording were the result of several years of cooperation between Bělohlávek and Dagmar Pecková. Mahler became a major element in the repertoire of this Czech mezzosoprano and Bělohlávek was instrumental in it from the start: “I was lucky that in 1988 Jiří Bělohlávek, the then chief conductor of the Prague Symphony Orchestra, asked me to substitute for the alto Eva Randová, who was ill, in Mahler’s Second Symphony. That’s how I got “caught” and I began to fall for Mahler.” [ 5 ]

Dagmar Pecková had her Mahler debut also with the Czech Philharmonic in 1989, again with Bělohlávek. Not only the orchestra, but also the work that she sung – Song of the Earth, were new to her: “…this was my debut with the Czech Philharmonic and Jiří Bělohlávek. My mother was dying and I was five months pregnant at the time, and even so, I began to love the composition dearly. This was also due to the fact that, right from the start, I had the opportunity to work on it with Jiří Bělohlávek, who was – as everybody knows – a conductor who knew how to accompany singers and knew about vocal phrasing. He was able to oblige in everything and to build everything in an amazing way.” [ 6 ]

The two collaborated on the Song of the Earth more than once also with the PKF – Prague Philharmonia. In 2005, they performed the work at the Smetanova Litomyšl Opera Festival, where the Austrian tenor Herbert Lippert was Pecková’s singing partner.

As far as the Czech Philharmonic is concerned, Bělohlávek started performing Mahler’s work in the late 1970s. Coincidentally, the orchestra was recording all Mahler’s symphonies under Václav Neumann between 1976 and 1982. The players therefore could get to know a different kind of interpretation with Bělohlávek than to which they were used to with their chief conductor.

In 1978, Bělohlávek and the Czech Philharmonic played Symphony No.1 in D major in a concert. “In Bělohlávek’s approach, everything was subordinated to the overall impression. The conductor did not show off as a virtuoso, but rather worked as a perfect architect. The level of monumentality that he achieved with his modest gesture and the sonorous fullness in the ländlers is almost hard to believe. The orchestra was excellent …” Miloš Pokora wrote in a review. [ 7 ]

At the turn of the 1970s and 1980s, Prague audiences could enjoy Mahler to the full. Orchestras had his work in their concert plans for 1980 to commemorate the composer’s 120th anniversary and 70 years from his death.

Music-lovers could compare Neumann’s Mahler with the Czech Philharmonic with Bělohlávek’s Mahler with the Czech Philharmonic or with the Prague Symphony Orchestra, as did a review published in Lidová demokracie assessing the performance of the First Symphony given by the latter orchestra and Bělohlávek.

Mahler was in the centre of the concert and Bělohlávek prepared for it diligently – he conducted by heart – and put in it all his musicality and intellect. He stood the test of the tough competition with Neumann’s striking creations: his Mahler was perhaps softer, more dreamy and less shiny, but also with a more compact build-up, gradually moving to the final core of this beautiful confession of love, nature, and of the enchanted, wounded, wrestling and again rising soul of man.

In 2008, Bělohlávek and the Czech Philharmonic took part in an important event. On 19 September, they performed Mahler’s Seventh Symphony, a hundred years to date after its world premiere, conducted in 1908 in Prague by the composer himself.

“Jiří Bělohlávek managed to study, perform and elucidate the colossus of the Seventh Symphony in such a way that there was no need to add anything, that it was not necessary to justify the work and its inclusion on the programme and remembering it. (…) While listening, one could experience mystical moments, moments of outbursts and clashes and feelings of a certain mirroring. The symphony did not emphasise conflicts and contrasts, it was moderate, but in a positive way. With immense sound imagination and full of ceaselessly evolving richness of metamorphoses. And with a substantial portion of romanticism and solemn ceremoniousness in the final part (reminiscent partly of Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg), accumulating overpowering sound and expression. Jiří Bělohlávek knows, knows how and feels, he is at his best.” [ 9 ]

Bělohlávek performed Mahler also with orchestras abroad. The opening concert of the BBC Proms in 2010, closely followed by the media, featured Mahler’s monumental Symphony of a Thousand (Symphony No.8). He had conducted the work only once before in the mid-1980s with the Prague Symphony Orchestra. The summer was traditionally dedicated to the Proms. Here he conducted the BBC Symphony Orchestra and five hundred singers of several choirs on the occasion of the celebration of Gustav Mahler’s 150th anniversary.

Following Bělohlávek’s return to the Czech Philharmonic in 2012, Mahler could not be missed either. He was included already in the programme of Bělohlávek’s inauguration concert by five songs composed on the words of the collection Des Knaben Wunderhorn performed by the Canadian baritone Gerald Finley.

At subscription concerts in April 2015, Bělohlávek conducted Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 in C minor, Resurrection, with Bernarda Fink, and two months later, his Symphony No. 3 in D minor at the 70th Prague Spring Festival.

Mahler was performed in 2015 also in a slightly different format. The second movement of his Seventh Symphony was the topic of an educational programme “Zkouška orchestru: Rozšťourávání Mahlera (An Orchestra Rehearsal: Poking into Mahler)” where Bělohlávek and the presenter Marek Eben examined what happens at an orchestra rehearsal in a fun way. The conductor even shared the fantasies various motifs evoked in him.

Mahler was also on the programme of Bělohlávek’s very last concert with the Czech Philharmonic. Friday 5 May 2017, the Dvořák Hall of the Rudolfinum, the last night of the three subscription concerts of the B Cycle. The audience first heard Mozart’s Violin Concerto in A major performed by Nikolaj Znaider and, after the intermission, Mahler’s Symphony No. 5 in C sharp minor, which Mahler edited for print in 1911 as the last work he did.

Great conductors first listen to what Mahler tells them and then they help us listen and perceive. Mahler creates a planned-out logical structure to be understood without the need for verbal explanation. In other words, the symphony draws from a chorale and comes back to it in its final part. That was Bělohlávek’s interpretation we heard yesterday; it helped the listeners understand the content of the work. And of course, it merited standing ovations.

This performance of Mahler’s symphony was awarded in the orchestral category of the Classic Prague Awards 2017.

Unfortunately, Bělohlávek was no longer able to complete the planned recording of all of Mahler’s symphonies with the Czech Philharmonic. This task was taken over by Semyon Bychkov, his successor on the post of the chief conductor of the Czech Philharmonic.

Main sources

- 1.

(bez autora): Pecková s Bělohlávkem natočila Mahlerovy písně na CD. Práce 1996 (17. 1.), č. 14, s. 13

- 2.

GOLDSCHEIDER, Alexander: Jiří Bělohlávek: A Life in Pictures. 2017. Kniha na více než 600 fotografiích a 160 stránkách dokumentuje celoživotní dráhu Jiřího Bělohlávka s použitím tisíců unikátních statistických údajů. Available online

- 3.

VÍT, Petr: Bělohlávkův Tomášek a Mahler. Hudební rozhledy 1975, č. 6, s. 256

- 4.

PEČMAN, Rudolf: Mahlerovský konec století v Brně. Lidové noviny 1994 (17. 9.).

- 5.

KOVAŘÍKOVÁ, Gabriela: Dagmar Pecková: Mahler a Wagner? Překvapují mě svou dokonalostí. Denik.cz 2014 (20. 5.) Available online

- 6.

JÄGER, Daniel: Dagmar Pecková si splnila životní sen. Vydává Mahlerovu Píseň o zemi. Český rozhlas Vltava 2018. (16. 3.) Available online

- 7.

POKORA, Miloš: Hudební rozhledy 31, 1978, č. 7, s. 304.

- 8.

Pražským koncertním životem. Lidová demokracie 1980 (2. 10.), č. 233, s. 5

- 9.

VEBER, Peter: Mahler sto let poté. Harmonie 2008. (17. 12.) Available online

- 10.

NOVÁČEK, Libor: Fascinující kontrasty Bělohlávkova Mahlera a průzračný Mozart Nikolaje Znaidera. Opera Plus 2017 (.4. 5.). Available online

(bez autora): Pecková s Bělohlávkem natočila Mahlerovy písně na CD. Práce 1996 (17. 1.), č. 14, s. 13

GOLDSCHEIDER, Alexander: Jiří Bělohlávek: A Life in Pictures. 2017. Kniha na více než 600 fotografiích a 160 stránkách dokumentuje celoživotní dráhu Jiřího Bělohlávka s použitím tisíců unikátních statistických údajů. Available online

VÍT, Petr: Bělohlávkův Tomášek a Mahler. Hudební rozhledy 1975, č. 6, s. 256

PEČMAN, Rudolf: Mahlerovský konec století v Brně. Lidové noviny 1994 (17. 9.).

KOVAŘÍKOVÁ, Gabriela: Dagmar Pecková: Mahler a Wagner? Překvapují mě svou dokonalostí. Denik.cz 2014 (20. 5.) Available online

JÄGER, Daniel: Dagmar Pecková si splnila životní sen. Vydává Mahlerovu Píseň o zemi. Český rozhlas Vltava 2018. (16. 3.) Available online

POKORA, Miloš: Hudební rozhledy 31, 1978, č. 7, s. 304.

Pražským koncertním životem. Lidová demokracie 1980 (2. 10.), č. 233, s. 5

VEBER, Peter: Mahler sto let poté. Harmonie 2008. (17. 12.) Available online

NOVÁČEK, Libor: Fascinující kontrasty Bělohlávkova Mahlera a průzračný Mozart Nikolaje Znaidera. Opera Plus 2017 (.4. 5.). Available online