It was a happy time for me when we had the opportunity to take care of the real core of music, to try to delve deeply into the secrets of scores. In the chamber frame, it was really a refining job as if we were polishing a diamond in a goldsmith’s workshop. It was very nice, both in terms of music and of human relationships. For me, it is a kind of island of beautiful eleven years.

The core of the Prague Chamber Philharmonia – that has been known by the name of PKF – Prague Philharmonia since its twentieth season (2013/2014) - was founded in the early 1990s. It began as a group of about twenty young Czech string players studying at universities and conservatoires who met in the Gustav Mahler Jugendorchester (Youth Orchestra).

Gustav Mahler Jugendorchester

It is an international ensemble founded in 1986 by the world-famous conductor Claudio Abbado whose mission was to develop Gustav Mahler’s musical legacy. Before 1989, the orchestra gathered talented young musicians from Austria and other Central European countries. Twice a year, there were strict auditions selecting talented students from music schools, followed by study camps and tours. Thanks to collaboration with famous conductors, the orchestra is still very popular and performs regularly at major festivals in and outside Europe.

After completing their stay with the Youth Orchestra, the young string players wanted to continue in music-making together and so they decided to establish an orchestra which they named Giovani virtuosi da camera. The violinist and a student of conducting at JAMU in Brno Tomáš Hanus was a member and a major organiser and leader of the whole project.

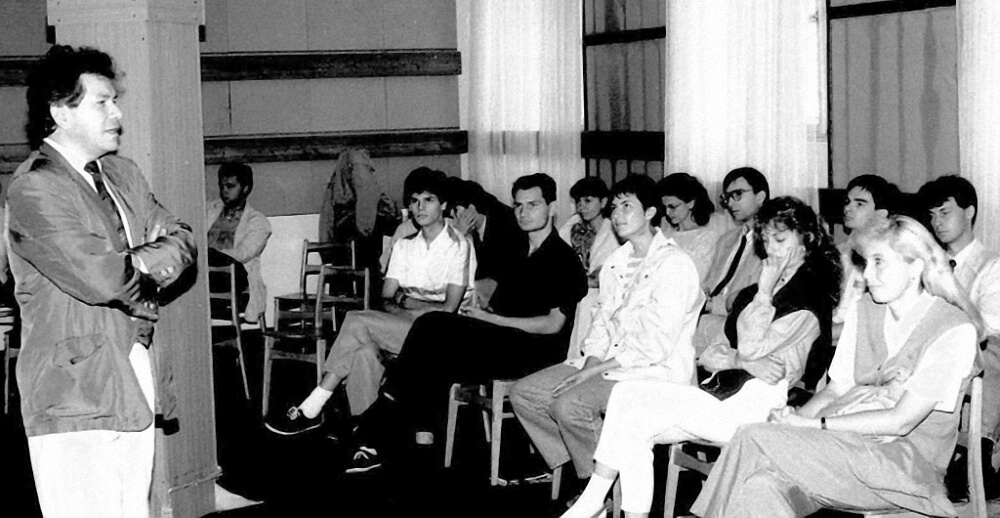

It was from him that Bělohlávek learned about the Giovani virtuosi and subsequently took part in the orchestra’s study camp in Machov in East Bohemia during the summer holiday of 1992. Having recognized the extraordinary quality and enthusiasm of the ensemble, he was happy to respond to Hanus’ request of supporting him in the role of an artistic guarantor.

We met for the first time at a study camp in Machov in East Bohemia. And that was a truly wonderful moment as there a group of young musicians gathered, eighteen or twenty years old, with a burning passion to create an ensemble and play together. (…) We were enjoying our summer holidays and on top of that we had a rehearsal every morning that I was leading and where we were getting to know each other. And they got their first experience with chamber music. A great friendship was being born, and the Prague Chamber Philharmonia was later born from this breeding ground.

He was very friendly, he would prepare breakfast with us, go on trips with us. In the meantime, we rehearsed intensively. One could call it joyful drill. We played from morning till evening – first we played in instrument sections, then all together with Tomáš Hanus and then with Jiří Bělohlávek… I have very fond memories of it. Not only did Jiří Bělohlávek as a former cellist have an exact idea about the sound quality, but he also knew how to make it.

The orchestra soon changed its name to the New Czech Chamber Orchestra and in the course of 1993 started to be noticed in artistic circles and in the media. In August 1993, the orchestra performed to mark the occasion of the re-opening of the Church of Sts. Simon and Jude in Prague, where concerts have been held regularly since.

This concert was recorded briefly by a television camera for the documentary film about Jiří Bělohlávek called Tenerezza. The first part of the performance was conducted by the orchestra’s director Tomáš Hanus, the second half by Jiří Bělohlávek. At a show of young musicians called Young Stage ’94 in Karlovy Vary, the ensemble won an award and started recording a CD for the Supraphon label with the works of Arnold Schönberg and Pavel Haas in April of the same year. The CD entitled Schönberg/Haas was released in January 1995 and because the recording process lasted several months (April to November), the booklet stated that the first two compositions were recorded by the New Czech Chamber Orchestra and the next three by the Prague Chamber Philharmonia.

Parallel to these events, negotiations about a new representative ensemble of the Czech Army were conducted. Bělohlávek remembered how at the beginning of the whole project, an offer was made by the composer Ladislav Simon to found a new artistic platform on the ruins of the former Vít Nejedlý Army Art Ensemble. Bělohlávek did not want to have anything in common with the army; however, when the offer was repeated many times and a possibility of an ensemble provided for economically became real, he realized that his “aversion would prevent a group of young musicians from an amazing professional opportunity.” [ 4 ]

The scales tipped and Bělohlávek decided to enter negotiation about the actual form of the ensemble. The fact that his work with dedicated musicians helped him to feel that he was on the right and feasible path as far as his ideals and foundations were concerned played a significant role in his decision. “The Prague Philharmonia gave me a sense of stability in my artistic endeavours at a time when I was going through a relatively difficult period. Working with them, I regained my confidence and, with their help, built a new ensemble that today is one of the top orchestras.” [ 5 ]

Negotiations were surprisingly smooth. Bělohlávek’s conditions and wishes were accepted and a contract was prepared within a short time. Beginning 1 July 1994, the Army Art Ensemble changed its name to Art Studio of the Ministry of Defense of the Czech Republic and was led by the composer Ladislav Simon. The studio consisted of several ensembles: The Army Big Band, Bohemia Ballet and most importantly the Prague Chamber Philharmonic which replaced the symphony orchestra existing until then. Bělohlávek was the orchestra’s chief conductor with Tomáš Hanus as the second conductor. Ilja Šmíd was appointed the music director.

The contract provided the orchestra an economic guarantee ensuring a full financial support for the period of at least five years. Bělohlávek regarded the outcomes of the negotiations very positively: “The Ministry of Defense has offered me something wonderful in the sense that I will have the opportunity to work in peace and concentration and create a new ensemble systematically in a free-spirited creative space and without any external or internal pressure. Such are the guarantees I have received…” (in Denní Telegraf on 6 July 1994).

On 10 June 1994, the daily newspaper Lidové noviny informed of the foundation of a new orchestra and announced their first official concert: “The orchestra will introduce itself to Prague in the Spanish Hall of the Prague Castle on 17 November. And they say they are not going to play in uniforms.” [ 6 ]

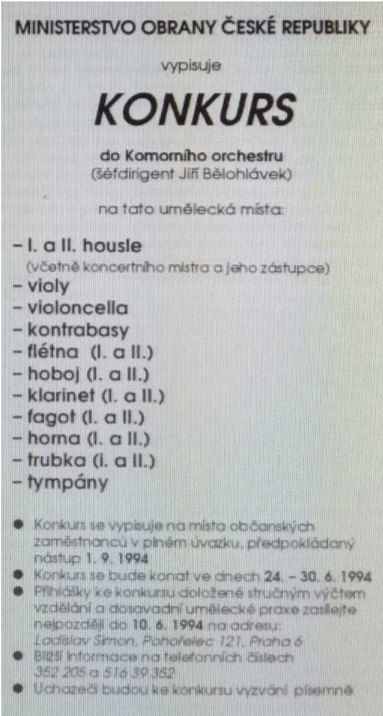

In the same week, auditions were announced for players of all required instruments. The number of applicants was enormous - one hundred and eighty-four, and, eventually, one hundred fourteen of them turned up. The name of Jiří Bělohlávek was magnetic. Although the string core of the orchestra was to be formed by members of the New Chamber Orchestra, Bělohlávek insisted everybody must take part in auditions, everyone was to have the same starting conditions. The orchestra was complete in early-July and on 1 August, the very first rehearsal took place in the rehearsal room of the former Army Art Ensemble at Pohořelec in Prague.

Bělohlávek started to make his ideal of orchestral playing come true. He had always put an emphasis on the quality of ensemble playing and now he had ideal conditions to fulfil his vision. He had the time to work with one ensemble on a long-term basis. It was a chamber orchestra with a lower number of players which made the communication and cooperation easier. And most importantly, he worked with talented, conscientious and enthusiastic musicians who were not encumbered by routine and were happy to meet all his artistic requirements, to practice diligently at home and rehearse as long as was necessary without grumbling.

Bělohlávek established a specific rehearsing scheme, still practiced until today. “There were split rehearsals, either in sections according to instruments and parts - the first violin, the second, wind instruments etc. – or, every now and then, Bělohlávek would choose a specific group of instrumentalists - the fourth violinist, the second oboe, the first bassoon, the third cellist and the forth double bass player - that had to play a specified part of the piece together in front of the whole orchestra.” This drill and pressure were very important in that the players had to know well not only their parts, but also the scores and parts of the other instruments. So they knew “which way to play, with what force, whether piano or forte, how to phrase it, what legato and what agogics to make at every moment. And all this had a huge impact on the compactness of the orchestra’s sound. That is where the characteristic sound that the PKF has today was born.” [ 7 ]

The players worked so hard and had such great skills and the conductor knew how to lead them so efficiently that they decided to give their first concert two months before the originally planned concert of 17 November 1994. Progress in ensemble was audible every day and therefore Bělohlávek accepted the offer to perform at the official re-opening of the Žofín palace in Prague. The PKF played for the first time in public on 24 September 1994 with a programme of Smetana, Fibich, Dvořák, Czech folk songs and the Czech National Anthem. The soprano Eva Urbanová also performed; she knew the orchestra already as they were preparing a CD of Mozart arias together.

Another offer came in October: The Czech Philharmonic was on a tour abroad and thus the head of the office of the president, Chancellor Ivan Medek suggested the PKF play in the Vladislav Hall of the Prague Castle on the occasion of the state ceremony of 28 October. On 17 November the first official concert of the ensemble commemorated the fifth anniversary of the Velvet Revolution in 1989. The orchestra therefore returned to Prague Castle after three weeks, this time to the Spanish Hall to play Suk’s Serenade in E flat major, Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante for Four Winds with Jurij Likin on oboe, Ilona Vánská on flute, Tomáš Františ on bassoon and Radek Baborák on French horn, and Beethoven’s Second Symphony after intermission.

The first concert of Bělohlávek’s PKF became – surely due to the conductor’s enormous experience – not only a promise and pledge, but also a demonstration of high quality already achieved in all fundamental dimensions of performance. (…) The orchestra entered the uneasy competition of all Czech ensembles and the concert has shown us that it may be one of the candidates for the first place.

The PKF introduced itself in the best light everywhere. As a result of the ensemble’s quality and the chief conductor’s renown, a number of concert offers came swiftly and they recorded five CDs within the first year of the orchestra’s existence only. The orchestra started to give concerts – six concerts in the first season - at the Rudolfinum and to tour the country. They played in Litoměřice, Písek, Pardubice, Ostrava, and Kroměříž. They were invited to play at the Prague Spring Festival 1996. On 6 May 1995, their quality was officially acknowledged by the prestigious Classic ’94 Feat of the Year award received in Litoměřice and broadcast live on TV. Two members of the orchestra, the clarinet player Ludmila Peterková and the French horn player Radek Baborák received awards as well. Nothing seemed to be in the way of further development and success. But the reality turned out to be different.

Talks of dissolving the orchestra appeared already in April 1995 and intensified in the following months, regardless of the guarantees given in the contract. Some members of the Parliament pointed out the fact that it was a luxury to finance a top orchestra from the budget of the Ministry of Defense, that it was a blatant example of wasting taxpayers’ money. And musicians and artists criticised the fact that the PKF, a brand-new orchestra, was working in greenhouse conditions and was funded exclusively from the state budget while other, more established, orchestras had to face market conditions and had to also fundraise independently. Even the salaries of the management and players were being discussed publicly.

The matter was not black and white, of course. An article by Jitka Slavíková in the Hudební rozhledy magazine looked at it objectively giving space to both sides and came up with a balanced evaluation of the whole situation: “There is no doubt that the quality of performance of the Prague Chamber Philharmonia has been so extraordinary that its existence is in jeopardy is of interest not only to a handful of experts, but also to the general public as well. However, the fact that the orchestra has worked under advantageous conditions is undoubtfully the truth as well. The “Czech” solution is simple: to eliminate these conditions instead of making an effort to create them for other ensembles alike.” [ 9 ]

Numerous negotiations between representatives of the orchestra and the Ministry of Defence resulted in the following solution: the orchestra would not be dissolved, but the Ministry would no longer finance it. The orchestra's management would try to find another body to support it. After 30 September 1995, any official connection of the orchestra to the Army would cease.

Both the management and the orchestra members were convinced that their work was meaningful and wanted to proceed. The whole summer and autumn were therefore filled with intensive activity with the aim of providing enough financial means and a home space for the orchestra. Milan Uhde, the Speaker of the Parliament, learned about the problems and saw it as his duty to find a way for the orchestra to continue. “The plan presented by the PKF was a convincing proof that it is not about saving something that has been lost anyway. It consists of a request for support of 11 million CZK to ensure activity until the end of the year. Next year, a third of the amount seemed to be necessary, and in the following years the orchestra has promised to do without subsidies from the state budget.” [ 10 ]

Uhde gathered support of MPs and arranged the transfer of the orchestra into a university orchestra under the Academy of Performing Arts, AMU. The money for the orchestra could be transferred to the university account immediately. However, having been pressured by many of the most influential professors, the rector took his support back. The orchestra nevertheless got some support elsewhere. The Smíchovské kulturní centrum (The Smíchov Culture Centre) Foundation took over the orchestra’s patronage temporarily. The foundation was located at the Ženské domovy in Smíchov where it also ran the Akcent Theatre. The premises of the theatre became a temporary shelter, home and rehearsing rooms for the PKF. The subscription concerts for 1995/1996 were funded by a sponsor - the Novell company.

The atmosphere of insecurity could never be felt during the performances of the orchestra whose second season was opened on 30 October at the Rudolfinum with Mahler’s Adagietto and Rückert Lieder with Dagmar Pecková, and Beethoven’s Triple Concerto and Seventh Symphony on the programme. Critics praised Bělohlávek’s interpretation of the Seventh as being untraditional and original “showing the evident qualities of the players and compact ensemble (exquisite winds, soft strings in homogeneous unity, detailed phrasing and thorough understanding of the musical text) and last but not least the expressive urgency (…) and perfectly balanced overall structure.” [ 11 ]

Although the orchestra acquired some stability, its legal status had to be resolved in the following months. In the end a new law establishing a new type of non-profit organisation, the charitable trust, solved the problem. Bělohlávek submitted a proposal for the establishment of a charitable trust, the Prague Chamber Philharmonia, which was one of the first to be registered on 13 March 1996. The financial and therefore existential struggle had not ended, but as Bělohlávek said later: “…the conditions originally promised by the Army were provided in the end by other means, at least in the first years. Later the situation got worse, there was less money and the costs got higher, it was much more complicated…” [ 12 ]

The orchestra continued to give concerts intensively. In 1996 they played at the Prague Spring Festival together with two young soloists, the violinist Pavel Šporcl and the pianist Nikolai Lugansky, and there was no doubt that the PKF ranked among the top chamber ensembles in the Czech Republic. “After two years of its existence, the PKF has become an ensemble of exclusive quality formed in Bělohlávek’s ideal image. The young age of musicians and their fresh approach to interpretation unencumbered by routine play a positive role here.” [ 13 ]

From Bělohlávek’s initiative, the orchestra performed on 1 June 1995 at the first Music of Thousands Festival in Mahler’s birthplace Kaliště u Humpolce. The festival was a part of the initiative to renovate Mahler’s house of birth. The PKF together with Dagmar Pecková gave a benefit concert in the local church. The whole event attracted international acclaim and drew further attention to local activities connected with Mahler.

In October, the PKF with the conductor Tomáš Hanus toured Japan for the first time and gave five concerts there, in Tokyo and Osaka among other places. The programme consisted of Mozart’s opera overtures and arias, in which the orchestra accompanied the young soprano Zdena Kloubová, a soloist of the National Theatre in Prague, and of Dvořák’s Czech Suite and Martinů’s Serenade no. 2.

We admired the acoustically perfect concert halls in each of the cities we played in and the Japanese audiences admired our playing. Where else can one experience applause while leaving the concert building than in Japan?

Immediately after their return, the orchestra had a week of concerts for elementary school pupils, prepared by Lukáš Hurník, under the title Hudební Czech-made (Musical Czech-made). The same programme was performed for children and parents at the Akcent Theatre. Starting in the second season, the orchestra's educational activities were developed and over time they became innovative programmes that are still popular with schools and the public.

On 18 November 1996, subscription concerts of the PKF started at the Rudolfinum, opening with a night dedicated solely to Mozart with a programme of Sinfonia Concertante in E flat major for violin, viola and orchestra with Ivan Ženatý and Josef Suk, and Mass in c minor K. 427 with the Prague Philharmonic Choir led by Pavel Kühn and four soloists of Czech and Austrian origin.

Hundreds of concerts followed in the subsequent years: subscription concerts, festivals. In 1997 they returned to the Prague Spring Festival with Dvořák’s Legends and Biblical Songs, and Beethoven’s Eroica. In 1998, they played Beethoven’s Ninth on the final night of the festival and in the summer, gave two concerts at a festival in Český Krumlov, the first consisting of the works of Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, Brahms and Beethoven and the second accompanying Dagmar Pecková.

Thanks to music, the orchestra visited many far-away lands. They were common guests in the Middle East, in July 1998 in Jordan or in later years at the Royal Opera House Muscat in Oman. In August 2003 they toured Switzerland, performing at festivals in Murten and the Shlomo Mintz Festival and International Violin Competition in Sion. In March and April 2004 they returned to Japan, and in October of the same year they went to North America for the first time, giving concerts in Alaska’s Fairbanks and Anchorage, among others.

The orchestra often accompanied renowned vocal soloists: Eva Urbanová, Dagmar Pecková and Magdalena Kožená from the Czech Republic or the sopranos Diana Damrau and Nino Machaidze and tenors José Cura, Rolando Villazón or Juan Diego Flórez. In April 2005, they accompanied Luciano Pavarotti in a concert given in Sazka Arena in Prague as part of his last tour in Prague. Because of economic reasons, the orchestra sometimes ventured into the genre of popular music and made a Christmas tour with the pop singer Lucie Bílá in 2002.

The orchestra gradually cultivated its sound at rehearsals and concerts, in interaction with renowned musicians, various musical eras and styles, and such variety widened the players’ musical horizon. Bělohlávek deliberately strove for this in his programme planning: “From the very start, I have tried to give my musicians the widest musical outlook possible and to offer them practical experience with different stylistic periods and genres. With this in mind, I have used guest artists specialising in different styles (…). I am convinced that working with different experts brings the necessary variety in repertoire and interpretation, it creates a magnet for the audience as well as benefits the artistic growth of the orchestra.” [ 15 ]

The chief conductor and his team tried to include not only popular and sought-out pieces in the concert programmes, but also lesser known compositions, such as those of the Swiss composer Frank Martin or Richard Strauss’s Symphony for Wind Instruments played at one of the subscription concerts in 1999. The music critic Petar Zapletal appreciated Bělohlávek’s bold dramaturgical direction: “It seems that the five years of Bělohlávek’s hard work have prepared the ground very well – the Dvořák Hall was sold out on 18 April although the programme did not include any of the common attractions. The fantastic interest the concert attracted has shown that the PKF has by now its own trusting audience that follows its programme without prejudice.” [ 16 ]

From the very beginning, Bělohlávek tried to present the orchestra also on the music media market. The PKF recorded quite intensively with leading Czech and foreign performers. By 1999, the orchestra had already recorded over twenty albums for Clarton, Supraphon and Harmonia Mundi. By 2005, Bělohlávek’s last season as chief conductor, they had recorded forty-four albums. To name but a few: a CD with Mozart arias with Eva Urbanová – Vado, ma dove? (Clarton, 1994), a CD with Mahler’s music with Dagmar Pecková – Mahler (Supraphon, 1996), a double CD with Jan Křtitel Krumpholtz’s harp concertos with Jana Boušková on the harp (Clarton, 1996), (Clarton, 1996), Legends and Czech Suiteby Antonín Dvořák (Clarton 1996), Mozart’s compositions for violin and viola with Ivan Ženatý and Josef Suk – Mozart (Clarton 1998), an album Antonín Dvořák – Slavonic Dances (Clarton 1998), Chopin’s piano concertos with Jan Simon – Chopin (Clarton 1998), Martinů (Supraphon 1999) presenting Tears of the Knife and The Voice of the Forest, recordings with Ivan Moravec (Beethoven – Franck – Ravel, Supraphon 2004) and many more CDs presenting compositions by Vítězslav Novák, Beethoven, Jan Václav Hugo Voříšek, Jan Václav Stamitz and others.

The recordings were mostly very well received both at home and abroad and the mastery of the orchestra and soloists was praised in reviews. While reviewing a CD of Mozart’s Prague Symphony and Voříšek’s Symphony in D major, Christoph Schlüren in the German magazine Fonoforum stated that “the PKF is one of the greatest orchestras internationally, surpassing the Czech Philharmonic in its recordings. (…) Mozart’s Prague Symphony is one of the most anchored, complete and transparent recordings of the piece in the whole recording history. (…) In Bělohlávek’s interpretation with all its phenomenal composure, energetic spontaneity is not lost. (…) For me, it is the best recording of Mozart’s work in many years, by far surpassing the flatness of historically informed performances.” [ 17 ]

In the middle of 1999, Bělohlávek addressed all his collaborators in a letter assessing the five years of the orchestra and asked them to put their heads together about further developments of the ensemble in all aspects, including the question of who was going to be in charge. He was convinced that the fact that the PKF was generally perceived as closely linked to his person was no longer in place. It was justifiable in the orchestra’s early years but since then the PKF had grown into a top-class orchestra capable of meeting the most demanding requirements, regardless of which conductor stood in front of it. After discussion, however, Bělohlávek decided to keep the position.

Bělohlávek therefore went on giving many memorable concerts with the orchestra, for instance concerts with the Israeli-American pianist Yefim Bronfman. He was invited to Prague by the orchestra in January 2000 and played all five of Beethoven’s piano concertos in three evenings at the Rudolfinum. “Everybody knew that Bronfman’s playing would be fantastic, but no one could expect that he would make a fantastic Steinway out of the terrible piano in the rehearsing room which had made many a pianist suffer – that left us speechless,” remembers Martin Bialas of the PKF. [ 18 ]

Bělohlávek welcomed the new millennium with the PKF in style. On 1 January, the orchestra performed compositions that had been commissioned through the international Third Millenium Composition Competition. They played Elixirsby the Canadian composer Paul Frehner, the winner of the competition, and Triumph of Time by Zdeněk Lukáš, which had won the second place. After intermission, Beethoven’s Ninth concluded the concert that bore the name “To the Prometheuses and Icaruses”. Bělohlávek explained the title in the media: “We hope to assume that even in the third millennium there will be people who will strive to broaden the limits of human possibilities. Our concert is dedicated to those living and tireless spirits.” [ 19 ]

In October of the first year of the new millennium, Bělohlávek was officially distinguished by President Václav Havel and received the Medal of Merit of the First Grade.

The orchestra's skill deepened over the years, so that in her review of the 18 May 2002 concert, which featured pieces by Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy and Igor Stravinsky, Eva Vítová could write that the Philharmonia's qualities were improving constantly and that "the technical finesse and the sound balance, both of a high standard, light up each piece with the now-documented specific elements characteristic of this ensemble. (…) The audience can enjoy not only the self-evident quality but especially the constant and ever fresh joy of music anchored in great musicality of individual players and in a fusion with Bělohlávek’s interpretative intention. The fact that all pieces are meticulously prepared in advance enables the conductor to animate the orchestra only slightly during a concert and the players’s reactions are sensitive and immediate. Years of hard work on the part of the conductor and the players chosen by him result in an enormous joy of music making on all parts. And that’s why all concerts of the PKF give their audiences a chance to hear technical quality and musicality in symbiosis with pure joy.”[ 20 ]

Although the Prague Philharmonia was thriving artistically, from the economic point of view it struggled to maintain a positive economic balance and balanced cash flow. This can be seen from the 2003 annual report: “The budget deficit could not be fully eliminated and, particularly in the second half of the year, the solvency situation was very tight. For example, the payment of fees to external instrumentalists for the autumn trip to Paris was delayed until the beginning of 2004. Special grants of 650, 000 CZK provided by the Ministry of Culture intended for concerts for children and the Paris tour and also the chief conductor’s gift of 600,000 CZK helped to alleviate the deficit. Nevertheless, the December expenditures (salaries) paid in January were already at the expense of the balance of payments for 2004.” [ 21 ]

The year 2004 was one of the prominent years in the ensemble’s history and not only due to the high number of concerts given abroad (thirty-five), but also due to their significance. An example is a concert given at the BBC Proms on 21 July in London’s Royal Albert Hall presenting a selection of Czech music (Vejvanovský, Mysliveček, Martinů, Novák), and two arias by Mozart sung by Magdalena Kožená.

It was a fantastic debut of the PKF at the Proms, showing a standard not many chamber orchestras in London could match. The ensemble feeling and the technical maturity of the young orchestra that managed to overcome the unfavourable acoustics of the Royal Albert Hall were remarkable and even the slightest details were played with utmost precision and clarity and overwhelmed even English reviewers famous for their scepticism.

The tenth anniversary of the ensemble became an incentive for Bělohlávek to think again about the orchestra’s future development. This time he came to a definite conclusion: the time for a change had come. The change on the conductor’s post was scheduled for autumn of 2005 and Bělohlávek started to look for his successor intensively. After six months of negotiations and searching for options, including a survey among the orchestra members, he presented two proposals at the board meeting on 28 January 2005:

- Jakub Hrůša

- Kaspar Zehnder, jako druhý dirigent Jakub Hrůša

After some discussion, the board and a representative of the orchestra members chose the second option. Therefore, from the 2005/2006 season, the young Swiss conductor Kaspar Zehnder became the chief conductor. He had collaborated with the orchestra previously and was popular with the orchestra members. Bělohlávek remained with the PKF as the conductor laureate and the founder. Jakub Hrůša was appointed a conductor beginning in the 2005/06 season (later, between 2008 and 2014, he was its chief conductor), and Michel Swierczewski from France had his third season as the principal guest conductor.

Bělohlávek conducted his last subscription concert with the PKF in the role of the chief conductor on 25 April 2005, performing Martinů’s oratorio Gilgamesh. “There seemed to be no end to the audience’s enthusiasm, with musicians being called out time and time again. And so the concert ended with a beautiful gesture - a deep bow from the entire orchestra.” [ 23 ]

On 4 July 2005 Bělohlávek and the PKF played at the Smetanova Litomyšl Opera Festival. Together with the mezzosoprano Dagmar Pecková and an Austrian tenor Herbert Lippert they performed Dvořák’s Nocturne in B major, Petr Eben’s Prague Nocturne and Mahler’s Song of the Earth, one of Bělohlávek’s favourite compositions.

After eleven years, Bělohlávek left the position of the chief conductor, a position that he had planned to hold for five years only. In February 2006, he celebrated his sixtieth birthday and became the chief conductor of the BBC Symphonic Orchestra in London in the autumn, succeeding Leonard Slatkin. He was appointed for the period of three years.

Bělohlávek continued to have an excellent relationship with the PKF over the following years and conducted it at least once or twice a year, be it at subscription concerts, tours or on special occasions such as the “Už je to tady!” (It’s Here!) concert organized by Václav Havel in November 2009 to commemorate the twentieth anniversary of the Velvet Revolution and the fall of the Iron Curtain. At this concert the orchestra accompanied Renée Fleming, Joan Baez, Lou Reed and others.

The close relationship Bělohlávek had with the orchestra was symbolically sanctified at the end of the conductor’s life. His last concert ever was the opening concert of the Martinů Fest in Polička on 7 May 2017 where he conducted the PKF – Prague Philharmonia.

With other Czech orchestras

Despite the break-up in 1992, Jiří Bělohlávek continued his regular collaboration with the Czech Philharmonic. In 1992 and 1993 he fulfilled - as he had promised - all the contracted commitments, while new projects and opportunities also appeared.

Some of them were a result of sad events, such as a concert in September 1995. This concert was supposed to be conducted by Václav Neumann, who had led the orchestra for many years, and was supposed to be a celebration of the one hundredth season of the Philharmonic and at the same time of the conductor’s seventy-fifth birthday. Sadly, Václav Neumann died on 2 September and the concert of 28 September became a homage to him. Bělohlávek solved the uneasy situation and took over the programme consisting of Neumann’s favourite pieces, Mahler’s Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen with the baryton Ivan Kusnjer and Martinů’s Sixth Symphony without any change.

The forthcoming centenary had gained enormous publicity in Prague and other places, there were many jubilee projects and events in the second half of the year. New compositions had been commissioned with Czech and foreign authors such as Petr Eben, Milan Slavický, Marek Kopelent, Svatopluk Havelka, Krzysztof Penderecki and more. These compositions were performed during the jubilee and the following season. Supraphon prepared a special “Best Of” the Philharmonic edition of 101 CDs, where the orchestra is conducted by Václav Talich, Rafael Kubelík, Václav Neumann, Václav Smetáček, Zdeněk Košler and Jiří Bělohlávek.

And of course, there were many concerts. The most significant one was the official concert of 4 January 1996 where all four living chief conductors were supposed to conduct a programme identical to the programme of the very first concert of 4 January 1896 when the orchestra – named the Czech Philharmonic for the first time – was conducted by Antonín Dvořák himself. However, Rafael Kubelík was ill, and Václav Neumann had died, and so only Jiří Bělohlávek and Gerd Albrecht took turns.

The first part of the concert conducted by Bělohlávek included Dvořák’s Biblical Songs featuring Dagmar Pecková and the Slavonic Rhapsody, this was followed by the Othello overture and the New World Symphony conducted by Albrecht. The concert was broadcast live from the Rudolfinum on TV and radio in the Czech Republic and other five European countries.

Bělohlávek returned to the Czech Philharmonic already in February to conduct Viktor Kalabis’s Third Symphony. Back in 1972, he had premiered the piece with the Czechoslovak Radio Symphony Orchestra and recorded it with the Czech Philharmonic. Bělohlávek here “not only emphasised the profundity of the composer’s message but intensified it also by virtuosic interpretation." [ 24 ]

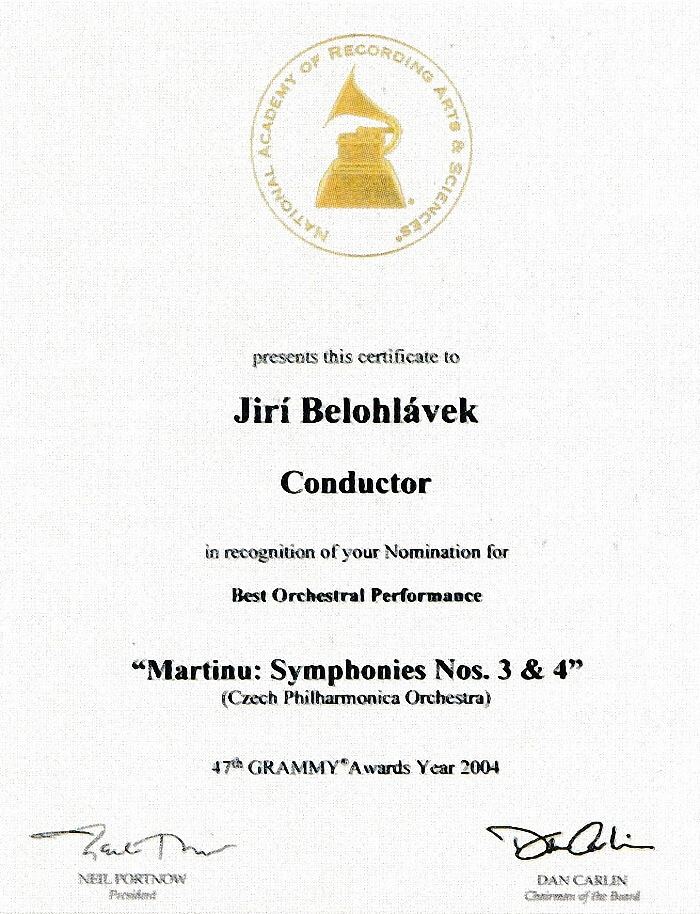

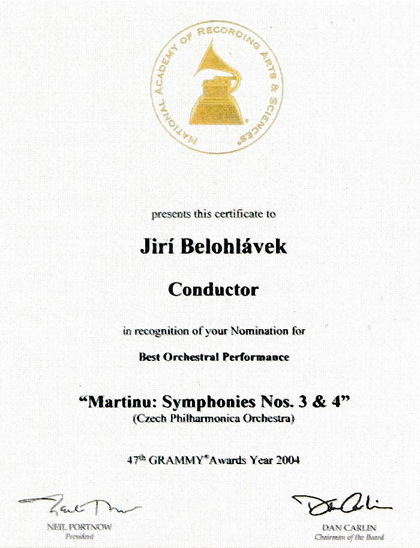

In 1996, Bělohlávek and the Czech Philharmonic made shorter tours to Switzerland and Italy. In 2002 they went on a tour of seven Japanese cities. In September 2003, they started recording a complete set of Martinů’s six symphonies, initiated by Supraphon and the Bohuslav Martinů Foundation. In addition to the quality of the performers, it benefited from technological advances in recording and from the detailed preparation of the scores which the players worked with. The first disc of the Third and Fourth Symphonies were released at the end of 2003 and were praised both at home and abroad. The recording was later nominated for the Grammy Awards in 2004.

Time and time again, I experience the beneficial influence Jiří Bělohlávek has on the Czech Philharmonic. The orchestra is concentrated, perfectly prepared and does what every ensemble should – fulfils the conductor’s vision perfectly. The orchestra’s performance is in both compositions fabulous (perhaps in the Third Symphony a tiny bit more still) and Bělohlávek again raised the interpretation level of difficult scores higher.

On 2 May 2004, Bělohlávek conducted the Czech Philharmonic at the Rudolfinum in a concert called “Homage to Antonín Dvořák” commemorating the centenary of the composer’s death. On that day, five different concerts took place in Prague, in which Dvořák’s chamber and symphonic music could be heard. This festival was crowned by a concert featuring the Cello Concerto in b minor with Jiří Bárta as the soloist and the New World Symphony: “The conductor, visibly focused, infected the whole orchestra with the Dvořák virus perfectly. Although not everything was one hundred percent, the overall impression was of a vivid, singing whole interesting in every single detail. On that evening, the Philharmonic played truly world-class.” [ 26 ]

And soon after on 15 and 16 May 2004, Bělohlávek and the Czech Philharmonic prepared a grandiose performance of Dvořák’s two-hour oratorio Saint Ludmila at the Prague Spring Festival. In the crowded Smetana Hall, they performed together with five top-class soloists – Eva Urbanová, Bernarda Fink, Stanislav Matis, Aleš Briscein and Peter Mikuláš and the Prague Philharmonic Choir and Bambini di Praga. A live recording of the concert was released by the Arco Diva label in 2005.

With an immense feeling for the musical detail of the individual parts and with awareness of the overall structure, Bělohlávek, who had already had multiple experiences with Saint Ludmila, filled the oratorio with clear content. Under his exact leadership, the soloists, choirs, and orchestra created a culminating monolith. Under his baton, the orchestra of the Czech Philharmonic glittered in breath-taking technical and onomatopoeic music…

The absolute heights belong to the Czech Philharmonic which under Bělohlávek’s clear and uncompromising gestures showed its best. The highly musical expression connected with all thinkable technical precision was equally the work of the inspired and very motivated conductor who has Saint Ludmila close to his heart... (…) To cut a long story short, Saint Ludmila was performed with warmth, nobility, and perfection.

Bělohlávek also appeared with the Czech Philharmonic regularly at subscription concerts. In January 2005, he premiered Milan Slavický’s Requiem. “Bělohlávek’s input was not only his accuracy and ability to illuminate the main message of the work, but also in his fluidity, his drive and guarantee of the highest quality.” [ 29 ]

Bělohlávek returned regularly to the Prague Symphonic Orchestra as well. On 13 October 1994, he celebrated the orchestra’s sixtieth anniversary by a concert at the Rudolfinum featuring works by Beethoven, Shostakovich, Mozart and Dvořák. The soloists were the cellist Jiří Bárta and the soprano Eva Urbanová. Bělohlávek received the Gold Record from Suprahon for having sold 30 000 CDs of Má vlast recorded in 1991 with the Czech Philharmonic.

On 10 September 1997, Bělohlávek opened the FOK’s subscription cycle C. The main magnet of the concert was the Latvian cellist Mischa Maisky playing Dvořák’s Cello Concerto. He overthrew the traditional way of interpretation of this masterpiece in a positive sense. “Jiří Bělohlávek proved to master his difficult task: he conducted everything by heart and showed excellent understanding of Maisky’s specific interpretative approach. He obliged the soloist in all details and adjusted tempos and expression to his requirements without at the same time being satisfied with mere accompanying. On the contrary: drawing from a common understanding of the work he asked for adequate urgency and let the orchestral part sound with full expression.” [ 30 ]

In September 2004, Bělohlávek conducted another birthday concert of the FOK. They opened the seventieth jubilee season together at the Old Town Square in Prague with Suk’s Fairy Tale and Janáček’s Sinfonietta.

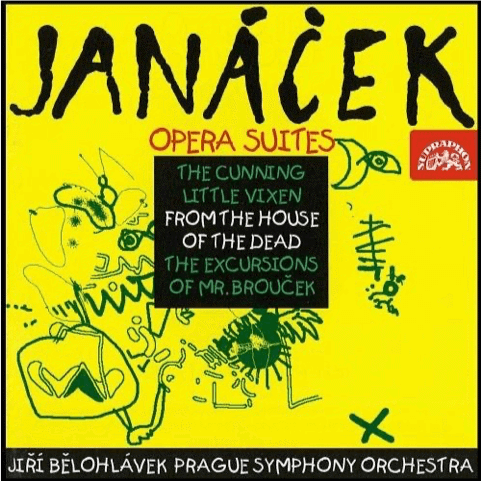

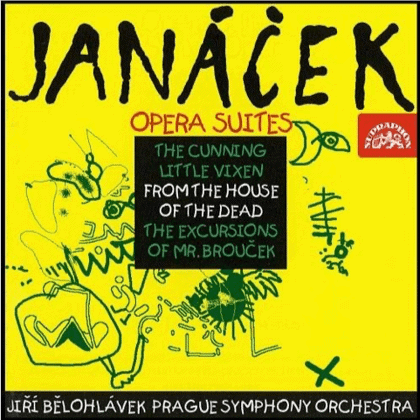

After 1989, Bělohlávek made a number of recordings with the FOK: a 1996 live recording for the Supraphon label of Dvořák’s Spectre's Bride with soloists Eva Urbanová, Ľudovít Ludha, Ivan Kusnjer and the Prague Philharmonic Choir led by Pavel Kühn; and a 1999 recording also for Suprahon of all three then existing suites from Janáček’s operas – The Cunning Little Vixen arranged by Václav Talich and Václav Smetáček, From the House of the Dead arranged by František Jílek, and a premiere of The Excursions of Mr. Brouček arranged by Jaroslav Smolka.

On the opera stage of the National Theatre in Prague

The second half of the 1990s brought Bělohlávek into intensive contact with opera. In March 1995, the Minister of Culture Pavel Tigrid appointed Bělohlávek as head of the opera of the National Theatre in Prague starting on 1 January 1998 until July 2002. Tigrid made his decision following recommendations from the Council of the National Theatre and after consultations with the conductor.

More on Jiří Bělohlávek and opera here →

Josef Průdek, an opera singer, a successful director and at that time also the director of the Opera House in České Budějovice, was to bridge the period between the departure of the previous head of the opera Eva Herrmannová and Bělohlávek's arrival: “At the moment when we agreed with Jiří Bělohlávek that my two-year position would be regarded not as transitional but as preparatory, the offer to work at the National Theatre began to make sense to me. Moreover, Jiří Bělohlávek invited me to collaborate with him also when he later was the head of the opera department.” [ 31 ]

Already since the autumn of 1995, Průdek and Bělohlávek planned together the following seven years in which they wanted to create conditions for the opera to reach the top European level. Their thinking went along the lines of restructuring the organisation, engaging top soloists from abroad and combining home and stagione ensembles.

In order to make their plans happen, Bělohlávek had made a condition of increasing the opera’s budget by thirty-five million CZK which was granted to him by the Minister of Culture Pavel Tigrid. However, after the general elections of 1996 and a change in the government, austerity measures were introduced that affected cultural institutions as well. For this reason, Bělohlávek resigned from the post, as he could continue with his conception only under the previously accepted conditions. Following the recommendation from the Council of the National Theatre, Jiří Průdek was appointed the head of the opera department for the following period. However, Bělohlávek continued to collaborate intensively. “In order ‘to make up for his sin’, Jiří Bělohlávek promised to be the principal guest conductor at the opera and to make and conduct one or two opera productions every season. He did as promised, as was his habit,” said Jiří Srstka, the then director of the National Theatre. [ 32 ]

Between 1997 and 2009, Bělohlávek participated in eight opera productions at the National Theatre. His most prolific period was from 1997 to 2002, when he staged six opera productions and conducted an average of thirty performances per season.

Bělohlávek’s Opera Productions at the National Theatre in Prague

|

Opera |

Director |

Premiere |

|

The Greek Passion (Bohuslav Martinů) |

Václav Kašlík |

Smetana Theatre, 26 January 1984 |

|

Jenůfa (Leoš Janáček) |

Josef Průdek |

National Theatre, 13 April 1997 |

|

Così fan tutte (Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart) |

Michael Sturm |

Estates Theatre, 18 June 1998 |

|

Rusalka (Antonín Dvořák) |

Alena Vaňáková |

National Theatre, 2 October 1998 |

|

Carmen (Georges Bizet) |

Jozef Bednárik |

National Theatre, 15 March 1999 |

|

The Devil's Wall (Bedřich Smetana) |

David Pountney |

National Theatre, 20 December 2001 |

|

Destiny (Leoš Janáček) |

Robert Wilson |

National Theatre, 19 December 2002 |

|

The Greek Passion (Bohuslav Martinů) |

Jiří Nekvasil |

National Theatre, 13 April 2006 |

|

The Miracles of Mary (Bohuslav Martinů) |

Jiří Heřman |

National Theatre, 29 October 2009 |

Main sources

- 1.

Mozaika 2007 (24. 10.) Rozhovor k zahajovacímu koncert 14. sezóny Pražské komorní filharmonie. Český rozhlas 2007

- 2.

Unikátní dvacetiletý příběh jednoho orchestru. 2014. TV dokument. Scénář a režie: Blažena Hončivárová, Martin Kubala. Available online

- 3.

SOJKOVÁ, Alena: Hana Kubisová. Orchestrální hráčka s komorními sklony. Harmonie 2019, č. 6, s. 24–36. Available online

- 4.

VEBER, Petr, STEHLÍK, Luboš: Jiří Bělohlávek. Fluidum, nebo práce? Harmonie 2016, č. 2, s. 6–15. Available online

- 5.

PKF – Prague Philharmonia. Unikátní dvacetiletý příběh jednoho orchestru. 2014. TV dokument. Scénář a režie: Blažena Hončivárová, Martin Kubala. Available online

- 6.

(vej): Vážná hudba bez uniforem. Lidové noviny 1994, č. 136 (10. 6.), s. 11.

- 7.

Radim Otépka z PKF: Za Jiřího Bělohlávka tu hudebníci dýchali. V jeho stopách jdeme pořád. Moderuje Vojtěch Babka. Český rozhlas Vltava. 14. 11. 2019. Available online

- 8.

ZAPLETAL, Petar: Hudební rozhledy 1995, č. 1, s. 5–6.

- 9.

SLAVÍKOVÁ, Jitka: Otazníky nad Pražskou komorní filharmonií. Hudební rozhledy 1995, č. 6, s. 2–4.

- 10.

UHDE, Milan: Rozpomínky. Co na sebe vím. Torst a Host, Praha a Brno 2013, s. 521.

- 11.

ZAPLETAL, Petar: Dvakrát Pražská komorní filharmonie. Hudební rozhledy 1996, č. 1, s. 9.

- 12.

VEBER, Petr, STEHLÍK, Luboš: Jiří Bělohlávek. Fluidum, nebo práce? Harmonie 2016, no. 2, p. 6–15. Available online

- 13.

Komorní orchestry na Pražském jaru. Hudební rozhledy 1996, no. 7–8, p. 12.

- 14.

BIALAS, Martin. PKF – Prague Philharmonia ve vzpomínkách. In: Dotkni se zvuku. Praha: PKF – Prague Philharmonia 2018, s. 22.

- 15.

JAROLÍMKOVÁ, Hana: S Jiřím Bělohlávkem o výsledcích i dalších projektech. Hudební rozhledy1996, č. 6, s. 2–6.

- 16.

ZAPLETAL, Petar: D. Geringas a F. Novotný s Bělohlávkovou PKF. Hudební rozhledy 1999, č. 6, s. 9.

- 17.

Převzato z Harmonie 2003, č. 10, s. 6.

- 18.

BIALAS, Martin. PKF – Prague Philharmonia ve vzpomínkách. In: Dotkni se zvuku. Praha: PKF – Prague Philharmonia 2018, s. 20.

- 19.

(čtk, kne): Filharmonici přivítají nový rok v Rudolfinu. iDnes 2000. 28. 12. Available online

- 20.

VÍTOVÁ, Eva: Bělohlávkova cizelérská práce. Harmonie 2002, č. 7, s. 6.

- 21.

Výroční zpráva za rok 2003. Pražská komorní filharmonie. Available online

- 22.

Vanda: Proms. Harmonie 2004, č. 9, s. 33.

- 23.

POKORNÝ, Petr: Bělohlávkův Gilgameš. Hudební rozhledy 2005, č. 6, s. 12.

- 24.

MLEJNEK, Karel: Dvě soudobá díla s Českou filharmonií. Hudební rozhledy 1996, č. 3, s. 4.

- 25.

STEHLÍK, Luboš: Bohuslav Martinů: Symfonie č. 3 a 4. Harmonie 2004, č. 1, s. 40.

- 26.

STEHLÍK, Luboš: Pocta Dvořákovi. Harmonie 2004, č. 4, s. 4.

- 27.

VÍTOVÁ, Eva: Pražské jaro 2004. Nádherná Svatá Ludmila. Harmonie 2004, č. 7, s. 4–5. Citace ze s. 5.

- 28.

TLUČHOŘ, Jiří: Pražské jaro: skvělá Dvořákova Svatá Ludmila. Novinky.cz 17. 5. 2004. Available online

- 29.

VEBER, Petr: Skromný triumf Milana Slavického. Harmonie 2005, č. 3, s. 4.

- 30.

ZAPLETAL, Petar: Mischa Maisky, Jiří Bělohlávek a FOK. Hudební rozhledy 1997, č. 11, s. 18.

- 31.

Nikdy neříkej nikdy! (Josef Průdek) In: Zindelová, Michaela: Sňatky s operou. 28 zastavení s umělci Národního divadla. Praha: Petrklíč 1997, s. 92.

- 32.

SRSTKA, Jiří: Opera a Jiří Bělohlávek. OperaPlus.cz 2017. 6. 6. Available online

Mozaika 2007 (24. 10.) Rozhovor k zahajovacímu koncert 14. sezóny Pražské komorní filharmonie. Český rozhlas 2007

Unikátní dvacetiletý příběh jednoho orchestru. 2014. TV dokument. Scénář a režie: Blažena Hončivárová, Martin Kubala. Available online

SOJKOVÁ, Alena: Hana Kubisová. Orchestrální hráčka s komorními sklony. Harmonie 2019, č. 6, s. 24–36. Available online

VEBER, Petr, STEHLÍK, Luboš: Jiří Bělohlávek. Fluidum, nebo práce? Harmonie 2016, č. 2, s. 6–15. Available online

PKF – Prague Philharmonia. Unikátní dvacetiletý příběh jednoho orchestru. 2014. TV dokument. Scénář a režie: Blažena Hončivárová, Martin Kubala. Available online

(vej): Vážná hudba bez uniforem. Lidové noviny 1994, č. 136 (10. 6.), s. 11.

Radim Otépka z PKF: Za Jiřího Bělohlávka tu hudebníci dýchali. V jeho stopách jdeme pořád. Moderuje Vojtěch Babka. Český rozhlas Vltava. 14. 11. 2019. Available online

ZAPLETAL, Petar: Hudební rozhledy 1995, č. 1, s. 5–6.

SLAVÍKOVÁ, Jitka: Otazníky nad Pražskou komorní filharmonií. Hudební rozhledy 1995, č. 6, s. 2–4.

UHDE, Milan: Rozpomínky. Co na sebe vím. Torst a Host, Praha a Brno 2013, s. 521.

ZAPLETAL, Petar: Dvakrát Pražská komorní filharmonie. Hudební rozhledy 1996, č. 1, s. 9.

VEBER, Petr, STEHLÍK, Luboš: Jiří Bělohlávek. Fluidum, nebo práce? Harmonie 2016, no. 2, p. 6–15. Available online

Komorní orchestry na Pražském jaru. Hudební rozhledy 1996, no. 7–8, p. 12.

BIALAS, Martin. PKF – Prague Philharmonia ve vzpomínkách. In: Dotkni se zvuku. Praha: PKF – Prague Philharmonia 2018, s. 22.

JAROLÍMKOVÁ, Hana: S Jiřím Bělohlávkem o výsledcích i dalších projektech. Hudební rozhledy1996, č. 6, s. 2–6.

ZAPLETAL, Petar: D. Geringas a F. Novotný s Bělohlávkovou PKF. Hudební rozhledy 1999, č. 6, s. 9.

Převzato z Harmonie 2003, č. 10, s. 6.

BIALAS, Martin. PKF – Prague Philharmonia ve vzpomínkách. In: Dotkni se zvuku. Praha: PKF – Prague Philharmonia 2018, s. 20.

(čtk, kne): Filharmonici přivítají nový rok v Rudolfinu. iDnes 2000. 28. 12. Available online

VÍTOVÁ, Eva: Bělohlávkova cizelérská práce. Harmonie 2002, č. 7, s. 6.

Výroční zpráva za rok 2003. Pražská komorní filharmonie. Available online

Vanda: Proms. Harmonie 2004, č. 9, s. 33.

POKORNÝ, Petr: Bělohlávkův Gilgameš. Hudební rozhledy 2005, č. 6, s. 12.

MLEJNEK, Karel: Dvě soudobá díla s Českou filharmonií. Hudební rozhledy 1996, č. 3, s. 4.

STEHLÍK, Luboš: Bohuslav Martinů: Symfonie č. 3 a 4. Harmonie 2004, č. 1, s. 40.

STEHLÍK, Luboš: Pocta Dvořákovi. Harmonie 2004, č. 4, s. 4.

VÍTOVÁ, Eva: Pražské jaro 2004. Nádherná Svatá Ludmila. Harmonie 2004, č. 7, s. 4–5. Citace ze s. 5.

TLUČHOŘ, Jiří: Pražské jaro: skvělá Dvořákova Svatá Ludmila. Novinky.cz 17. 5. 2004. Available online

VEBER, Petr: Skromný triumf Milana Slavického. Harmonie 2005, č. 3, s. 4.

ZAPLETAL, Petar: Mischa Maisky, Jiří Bělohlávek a FOK. Hudební rozhledy 1997, č. 11, s. 18.

Nikdy neříkej nikdy! (Josef Průdek) In: Zindelová, Michaela: Sňatky s operou. 28 zastavení s umělci Národního divadla. Praha: Petrklíč 1997, s. 92.

SRSTKA, Jiří: Opera a Jiří Bělohlávek. OperaPlus.cz 2017. 6. 6. Available online