„I found joy in music already as a little boy. My father was a judge, but he was also an excellent pianist and a passionate musician. He would play and practise at home every night, and I was therefore falling asleep hearing his piano playing. I should think that already back then I felt that music made me feel good; tucked in my little bed and listening to music, I felt exhilarated.“

Childhood and student times

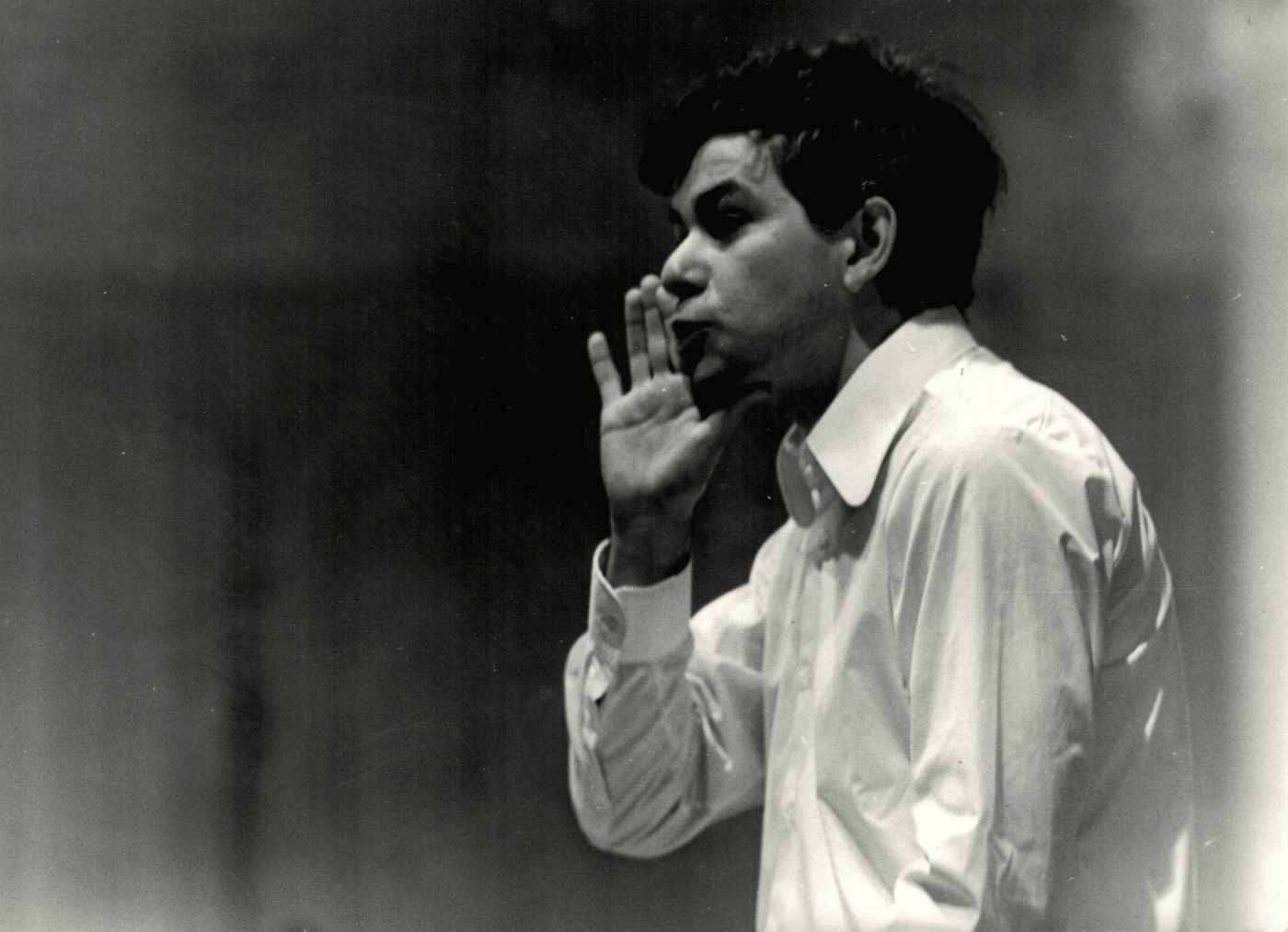

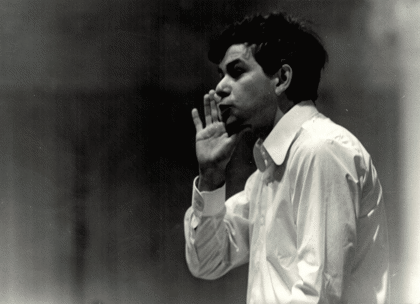

Jiří Bělohlávek was born on 24 February 1946 in Prague. His love of music started developing at a very young age, unknowingly at first when he was exposed to music naturally in his family, later by way of his own active music-making. His father Jiří was a lawyer and judge by profession and also a wonderful pianist. He would often make music alone or with friends at home, as well as in public. He was the accompanist for an amateur opera company, he performed with The Pardubice Symphony Orchestra and in the Czechoslovak Radio. When little Jiří was four years old, his father started to teach him the piano and the basics of music.

His interest in music brought Jiří Bělohlávek into the Prague Philharmonic Children’s Choir early on in his life. There he learned to sing a number of vocal compositions and took part in opera performances at the National Theatre.

Already then, he got to know the work of people who would be playing an important role in his later professional career. A quintessential example was Bohuslav Martinů, whose work Jiří Bělohlávek masterfully interpreted and promoted throughout his life. With the children’s choir and the Women’s Choir of the Czech Vocal Ensemble they performed Martinů’s The Opening of the Springs (Otvírání studánek) in preview on the 7th of December 1955 in the late-baroque Sylva-Taroucca Palace, known as Savarin, in Prague at an evening celebrating the composer’s 65th birthday. Miloslav Bureš, Martinů’s close friend and the author of the poems, shared his impressions of the evening in a letter to Martinů a couple of days following the event:

“The Opening of the Springs” was the concluding number of the evening and was such a success that people came up to me with tears in their eyes. And what if the Master Creator of the work had been present! Václav Talich was one of them, he was touched and enthusiastic at the same time. (…) Professor Kühn staged the work with true understanding and involved both women’s and children’s choir. The voices of the children were most touching.

Along with other performers, the Prague Philharmonic Children’s Choir also recorded this cantata. The recording took place on 14 and 15 December in the Domovina studio. It was, however, released only much later in 1959 together with some of František Škvor’s songs for children. You can listen to a short excerpt below.

The choir, with Jiří Bělohlávek in it, took part in the first World Choir Olympics in 1956 in Paris and won the first prize. According to the memoirs of Jan Farmer Obermayer [ 2 ]he, Bělohlávek and Josef Průdek (who later became an opera singer and director) were often soloists of the choir which helped them, or their voices, appear also on the silver screen. The three, together with Pavel Kühn and accompanied by the Film Symphony Orchestra, recorded the title song of the appraised and to these days popular film Death in the Saddle(Smrt v sedle, 1958). The music and text of the song entitled “Seno a stáj” (Hay and stable) fits in beautifully with the romantic pulp fiction atmosphere of the film.

The choir, or rather its choirmaster, stepped into the young musician’s life yet in another significant way. Walking together from a rehearsal, professor Kühn once told young Bělohlávek: “You are going to play the cello.“ At the next rehearsal, there was a cello ready for Bělohlávek and private lessons with professor Karel Pravoslav Sádlo had been arranged. Bělohlávek was just going to turn twelve. When soon after, in 1958, Jan Kühn died, Bělohlávek was one of those forming the guard of honour at his coffin at the Rudolfinum.

For more than ten years, singing in the Prague Philharmonic Children’s Choir was for me my main hobby and a wonderful school of music and of life, the latter I understood only in retrospect. Among the most cherished memories are our choir’s performances in operas staged at the National Theatre. “The Jacobin,” “Cunning Little Vixen,” “Jack’s Kingdom,” “The Grim Reaper” and, last but not least, the evergreen “Carmen” – those were the worlds that opened to us, lured us, beguiled us before they would become the love of our life and our destiny for many of us.

In spite of the unfavourable political situation of the 1950s, which affected Bělohlávek’s family directly (during political purges, his father was dismissed from the court where he’d worked), Bělohlávek remembered his childhood and family background as the fundamental value he drew from all his life: “Despite all the blows and mishaps that my father went through, together with my mum they managed to create for my sister and myself a haven full of harmony. Nothing from what went on around us did touch us children, I did not even notice it for a long time. (…) No one spoke of the horrors of communism. Our parents did not want to put the burden on us. Only much later, when I began to ask, did I learn of the difficulties our father went through. Until then I was interested solely in my studies: in music, choir, cello, and later orchestral scores.” [ 4 ]

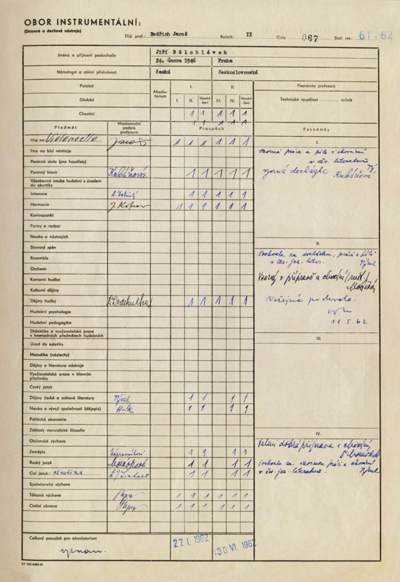

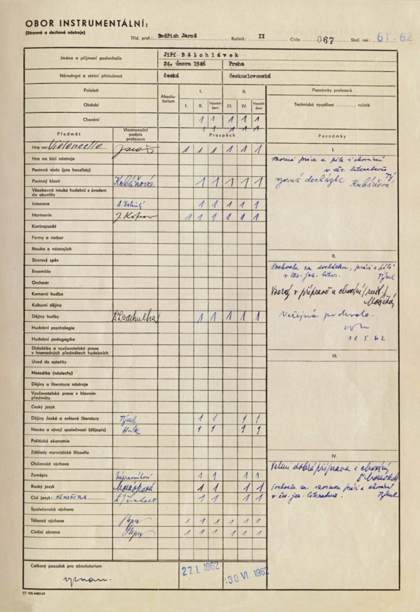

After primary school, Bělohlávek intended to apply for the conservatoire. In order to improve his knowledge of music theory, he started classes in The Music School of Prague in Voršilská street in the spring of 1960 and he joined its orchestra immediately. He passed the auditions to the Prague Conservatoire successfully and in September he started attending cello lessons with Professor Bedřich Jaroš. He was a diligent and successful student as testified by his school records, and together with his classmates formed his first chamber orchestra. He performed outside of school as well, every Saturday he would join in regular music gatherings organized by his father and his friends in their home.

In February 1961 his name appeared in the press for the first time ever. However, not in connection with his cello playing. Adventurous Beginners: A Youth Orchestra is the title of an article published in Mladá Fronta about an orchestra of thirty students conducted by a young Jiří Bělohlávek. [ 5 ]

Those were fantastic years for me, I bloomed both as a person and an artist. The school had, and still has I suppose, an amazing atmosphere. Students there feel as if they have stepped out of the ordinary everyday life and have entered a world in which music and art open the gate of a wonderful adventure. As I remember, not only that we as students felt very bohemian but the teachers and the whole school atmosphere encouraged us in feeling that way. Of course, the school required of us hard work but also provided us great self-confidence at the same time.

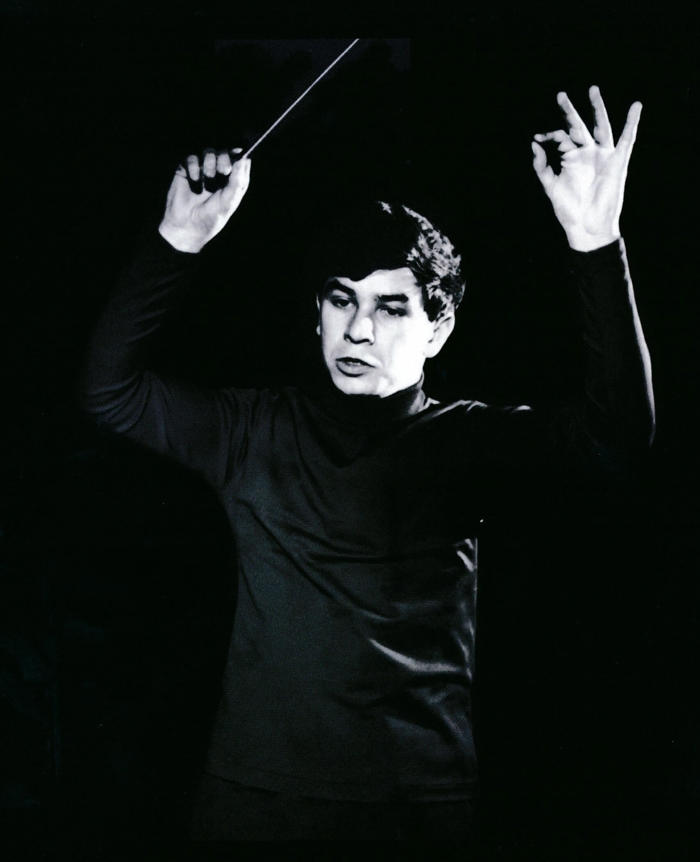

In the third year of the conservatoire Bělohlávek took up conducting as his second major subject. He was introduced to its secrets by Professor Bohumír Liška and František Hertl. Bělohlávek soon began to give preference to conducting over cello and he understood his cello playing as a good training for his future career as a conductor: “I am convinced to this day that a conductor must know a string instrument closely as phrasing and bowing are the core of symphonic play. I try to study the score also through the eye of the instrumentalist and, whenever possible, I play through the string parts on my cello.“ [ 7 ]

There was a legend known among musicians that the reason Bělohlávek became a conductor was that he‘d broken his hand playing ice-hockey on the frozen Vltava river as a boy. Later in an interview given shortly before his 60th birthday, he put this “legend“ to rest: „That was definitely not the main reason, but it is true that while studying the cello […] I would hit physical limits as a result of an accident from a boys’ game of ice-hockey. I couldn’t practice as long as I would have needed to, my hand would not obey me…" PLAVCOVÁ, Alena. Jiří Bělohlávek. Maestro. Pátek. Magazín Lidových novin 2005, č. 16, s. 4–10. Available online

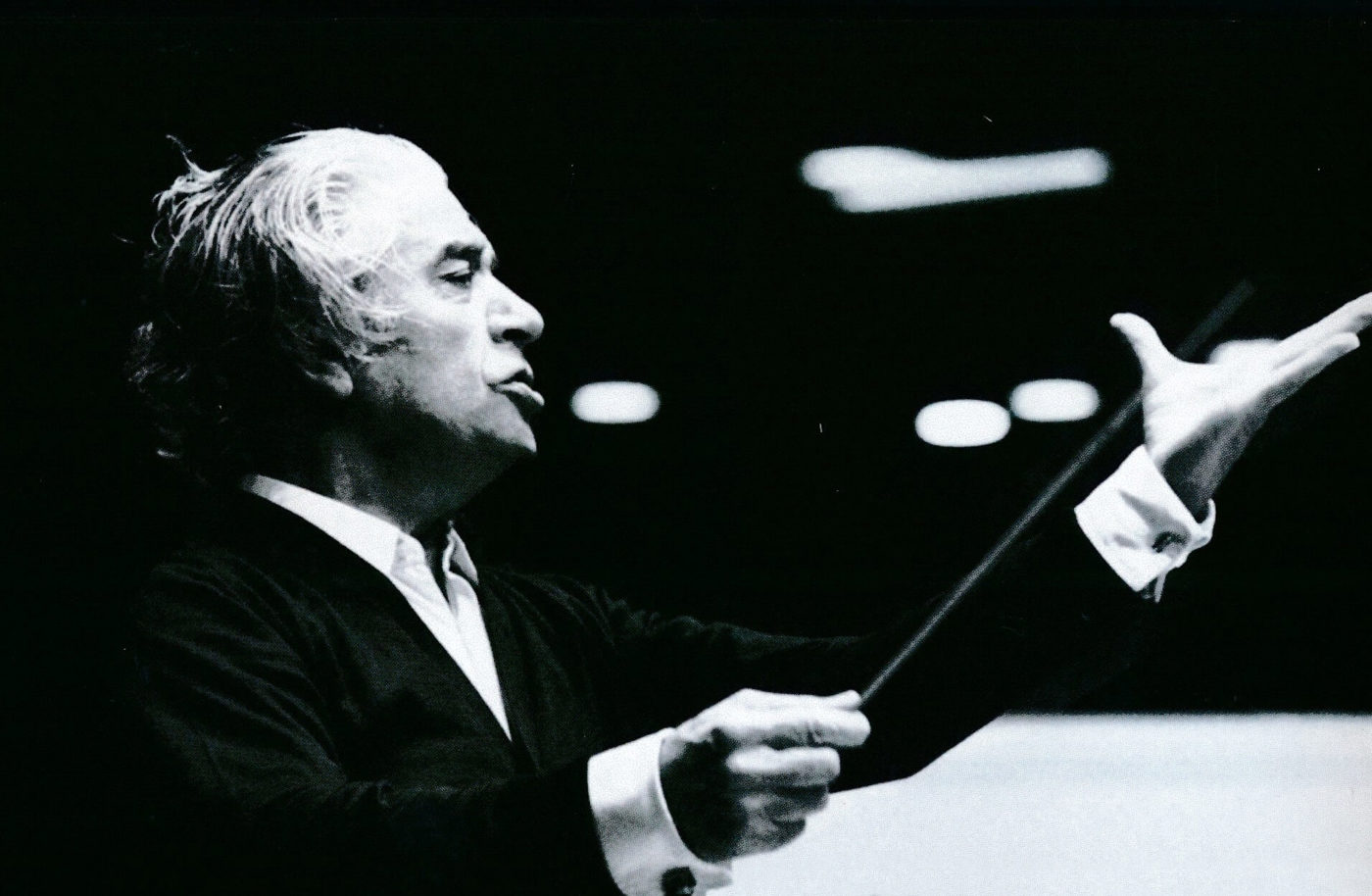

He graduated from the conservatoire in 1966 with excellent grades and conducted his graduation concert on 6 March at the Rudolfinum. It was the first time he stood with a baton in his hand on this famous stage of the Dvořák Hall, a hall in which he would later conduct almost four hundred concerts with the Czech Philharmonic, the Prague Philharmonia, and other ensembles.

Bělohlávek’s soloist career as a cellist had its peak in his final year of the conservatoire in a chamber duo with pianist Jan Novotný. Together they performed Bělohlávek’s cello graduation concert on 21 December 1966 and made tours in the German Democratic Republic and in India.

His studies at the conservatoire had not only a great influence on the development of Bělohlávek’s musical personality but also on his personal life. Through his cello playing he got acquainted with Anna Fejérová, a young pianist, whom he would later marry.

I got an offer to organize my own concert. I was asked to play the first half solo piano and the second half with a violinist or a cellist. I chose the cello and that is how I met Jiří Bělohlávek. We practised together for hours and I learned a great deal from him. From a young age he took music extremely seriously and responsibly and at the age of twenty-one he already was the conductor of a girls’ orchestra Puellarum Pragensis. I played a piano concerto with them a number of times, but Jiří wanted to keep his professional and personal engagements separate. He told me: “It could harm you if people think that you are given unfair preference.” It wasn’t a love at first sight, it grew out of friendship, affection, and experience from concerts we played together.”

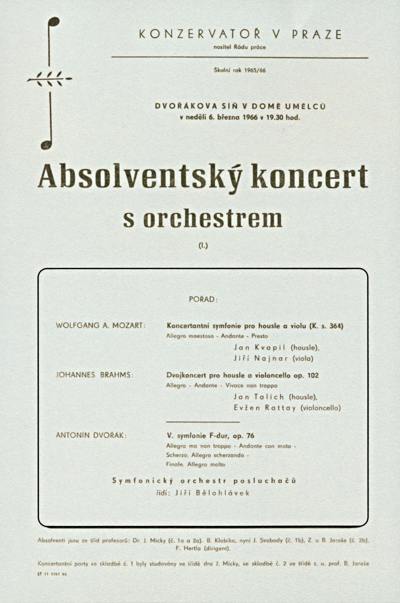

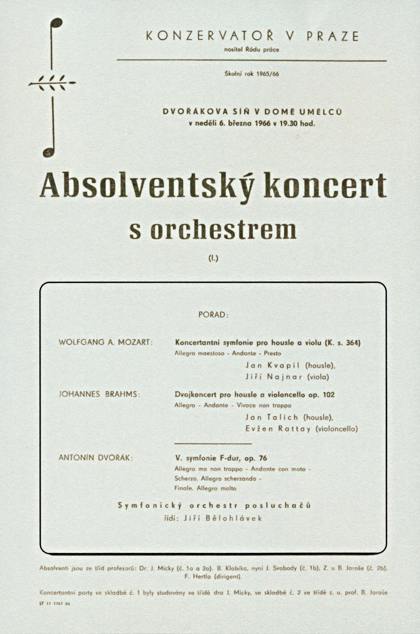

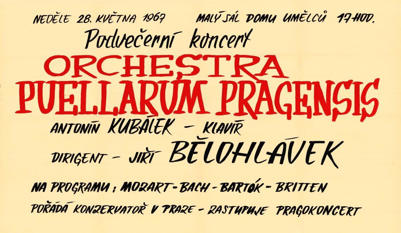

Having graduated from the conservatoire, he began studying at the conducting department of AMU, The Academy of Performing Arts in Prague. His teachers were Alois Klíma, Robert Brock, Josef Veselka and Václav Neumann. Besides his studies, Bělohlávek had also the opportunity to enhance his conducting skills practically. In February 1967 he became the artistic director of girls‘ string ensemble Orchestra Puellarum Pragensis that had been established in 1964. Under Bělohlávek’s leadership, the ensemble became a stable body of fourteen string players and rehearsed systematically. They performed works of contemporary composers in addition to classical repertoire. This was Bělohlávek’s first official orchestra; he led it for five years until 1972 and went on several tours abroad, the first of which was on 31 March 1969 in Kassel in the German Democratic Republic.

These young musicians do not want to play only old compositions, but also want to come closer to contemporary music. Recently they’ve found an excellent conductor, a twenty-one year old Jiří Bělohlávek, with whom the orchestra has studied and performed several contemporary Czech compositions, for example Lubomír Železný’s “Concerto for flute, strings and piano” which was a big success at the Festival of Young Artists in Jeseník. Some pieces were composed specifically for the ensemble: “Amorous Variations for barytone and strings” or the “Sonata for soprano and strings” by Oldřich Flosman, or “Serenata Giocosa” by Ivan Jirko.

In January 1968, Sergiu Celibidache came to Prague to conduct the Czech Philharmonic. On the occasion he led a master class for students of conducting from AMU. Bělohlávek also took part and at the end of the class, Celibidache invited him personally to attend similar courses in Stockholm that took place fortnightly in March and June of the same year. Bělohlávek accepted the invitation and added another course in Prague in February 1969. He studied Dvořák’s New World Symphony, Brahms’ First Symphony, Schumann’s Second and Ravel’s Ma mère l'Oye.

What I appreciate about Sergiu Celibidache's work is the exact idea of what he wants to achieve and the fascinating way in which he achieves it. I would like to follow his example as far as orchestra colour is concerned, but I allow myself to look for my own way concerning the approach to structure and expression.

In the second year of his studies at AMU, Jiří was obliged to suspend his studies due to compulsory military service. However, he could continue with his musical activities as he took up a position in the Vít Nejedlý Army Art Ensemble (AUS) in which young actors, directors and musicians could continue with their profession even during their military service. They could perform for soldiers from other army units as well as for the general public. Before Bělohlávek could participate fully in these activities, he had to take part in a month-long military training in Bor u Tachova. It was in the summer of 1968, the summer of the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia which started on 21 August.

At one point, the situation in Bor grew dramatic, as the unit’s commander was one of the brave who proclaimed that no support to Russian soldiers would be provided. Suddenly, we saw tanks encircling the whole camp, and that was a strange feeling. Our commander subsequently surrendered and provided them water and the troops left. No blood was shed but the terrible atmosphere of humiliation and the loss of trust in the friendship that had been proclaimed through those noble phrases and slogans over and over again – that stayed with us forever.

After the situation calmed down, Bělohlávek began to work as the assistant conductor of the army ensemble Czechoslovak Orchestra of Young Philharmonic Players at AUS. Later he remembered that, as a result of the loosening political atmosphere of the so-called Prague Spring, the orchestra was much more civil than military. Its players did not wear the military uniform and made tours to western countries as well. For Bělohlávek, the two-year long work for the orchestra constituted a very good school of musical repertoire.

Editor:

“And how do soldiers actually respond to classical music?“

Corporal Jiří Bělohlávek:

“I am convinced that the success of popular music is largely due to commercial reasons and good marketing. That’s why listeners are prepared to listen to such kind of music, unlike to classical music. This applies to concerts for military units as well that often fail as a result of trivial reasons – there is no functional lighting, or the soldiers had been crawling in mud shortly before the concert was due. Nevertheless, one concert for soldiers was very nice, it was for Žižka’s school in Hradec near Opava. It was the best audience I have ever experienced. The officers there are interested, they had prepared a lecture about the music before the concert and the boys came, and not because they were commanded to. I do not consider concerts for soldiers in any way less meaningful than for any other audience. Music affects the thoughts and feelings of all people alike.”

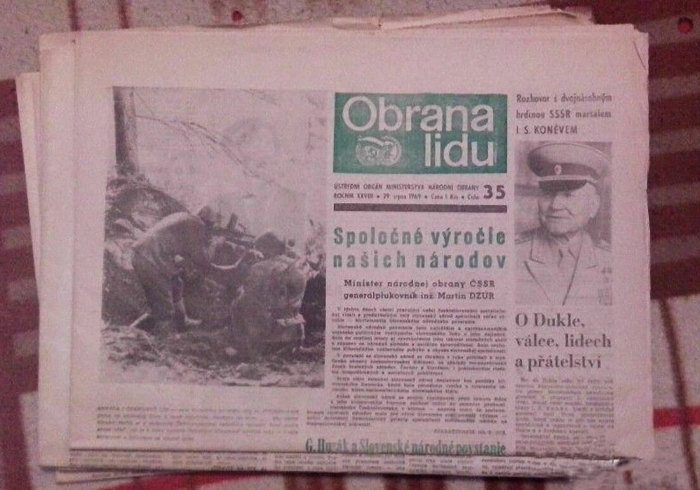

— Jiří Bělohlávek / Obrana lidu: list československé armády (People’s Defence: journal of the Czechoslovak Army) 1969

At the end of the 1960s, Jiří Bělohlávek also gained his first experience with musical theatre when the composer and conductor Ladislav Simon invited him to work with him at the Vinohradské divadlo (Vinohrady Theatre) in Prague. For five years, Bělohlávek provided musical advice, conducted the theatre orchestra and even composed music for some of the plays.

In September 1969, he was supposed to take part in the Herbert von Karajan conducting competition in West Berlin. On the eve of his departure, the police confiscated his passport. The communist regime once again tightened the reins and, for fear of their emigration, it banned its own citizens from travelling outside of the Eastern Bloc.

International Tribune of Young Artists

The Tribune (Tribuna) was both a platform of Pragokoncert focused on organizing cultural events as well as a subscription concert series designed to support young musical talents and to bring young audiences closer to classical music. Young laureates of international competitions from both Czechoslovakia and abroad performed to mostly young audiences at concerts and festivals organized by The Tribune.

In 1969, the Pragokoncert Agency and the International tribune of young artists committee selected Jiří Bělohlávek and the violinist Václav Hudeček as the most promising talents for a common concert of the International tribune. As a result, Bělohlávek conducted a concert on 1 December 1969 with the Brasilian pianist Arthur Moreira Lima who played one of Chopin’s piano concertos and with Václav Hudeček who played Mendelssohn’s e minor concerto. Both solo performances were complemented by Viktor Kalabis’ Concerto for Orchestra. And it was a success.

This concert was a double success for the International tribune of young artists. First, it drew a record high audience to the crowded House of Artists (Rudolfinum). Second it was filmed by the Czechoslovak TV which plans to broadcast it probably in May 1970 as two separate TV programmes.

In the following years, Jiří Bělohlávek and Václav Hudeček continued to appear at Tribuna concerts frequently, and they also collaborated extensively at concert of those ensembles. Bělohlávek then worked for FOK - the Brno Philharmonic, later the Prague Symphony Orchestra -. Together with eleven other promising talents, the Pragokoncert Agency chose to be their exclusive agent in 1971. Such a success was not without a downside, however. The participation of musicians in projects abroad was decided by one monopoly agency, which by the very nature of its function - to promote Czechoslovakia's cultural ties with other countries and thus help create a favourable image of the level of development in the socialist state - was closely monitored and controlled by the authorities: the Ministry of Culture, of Foreign Affairs, of the Interior and the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia.

In June 1970, Bělohlávek’s forty-year long collaboration with the Czech Philharmonic began. His debut with the orchestra took place on 9 June in the Smetana Hall of the Municipal House with a concert performed for participants of the 6thcongress of the International Federation of Concrete Workers. The all-Dvořák programme consisted of the b minor Cello Concerto with the soloist Josef Chuchro and the Eighth Symphony. A similar programme was performed several days later in Chrudim with the same cast.

Not two weeks had passed and Bělohlávek won a nation-wide competition for young conductors. In the finale that took place in Olomouc, he conducted Dvořák’s Noon Witch with the Moravian Philharmonic. The first prize included a one-year internship with the Czech Philharmonic as an assistant conductor. In the end, he held the position for two whole years.

The position constituted a major milestone in Bělohlávek’s career as it enabled him to conduct a leading symphonic orchestra and to develop his talents more quickly and intensively while working with prominent musicians of the time. On top of his conducting during rehearsals and regular consultations with Václav Neumann, who was then the chief conductor, he also got the opportunity to conduct concerts for the public, as was the case at the Fifth International Tribune of Young Artists in 1971 where the Czech Philharmonic performed at the opening night. They played Brahms’ Double Concerto and Béla Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra. Jiří Bělohlávek managed “to combine all three sections perfectly” in Brahms and he also excelled in the latter piece which “poses a serious challenge even for a more experienced conductor”. He “not only gave individual sections of the orchestra the space to excel in spectacular colours, but also succeeded in building a musical whole of expressive richness.” [ 13 ]

As an “apprentice” he was obliged to conduct also the unpopular “politically engagé” concerts and some less significant tours within the country. One concert of the former kind took place on 8 April 1971 and celebrated the 50th anniversary of the founding of the Czechoslovak Communist Party. At this concert, Jiří Bělohlávek “led the orchestra and the Prague Philharmonic Choir – wonderful as always - with impressive certainty and interpreted the Shostakovich especially with intense focus and remarkable sense of proportion.” [ 14 ]

One of the tours within the country included a tour of northern Bohemia. The Czech Philharmonic “started the tour in the town of Most, where they performed Dvořák’s Slavonic Dances as requested by the organisers. Interpreted by our first orchestra, these dances sparkled in full beauty of melody, rhythm and, above all, instrumentation, which is one of the strengths of this oeuvre, the most popular one of Czech orchestral work second only to Smetana’s Má Vlast. Our most talented young conductor, Jiří Bělohlávek, who was entrusted with the performance, showed us that he had his own understanding of the work and, without any showy effects, he carried out his task successfully.” [ 15 ]

In 1971, Bělohlávek got another opportunity to take part in the Herbert von Karajan Conducting Competition. This time he even received the exit permit, took part in the competition together with eighty-two candidates and beat his way through into the final where he won fifth place. He managed to put his intense preparation of previous years to good use: “I still recall that I worked one full year preparing for the Young Conductors Competition in Olomouc in 1970 and soon after for the Herbert von Karajan Competition in Berlin. For one year I’d been lying in the scores and whenever I needed any of the compositions later in my life, I did not have the slightest problem as I knew these works perfectly.” [ 16 ]

Bělohlávek’s success in Berlin generated attractive offers: an assistant conductor’s position with Herbert von Karajan or work for the Israel Philharmonic. Alas, politics intervened yet again. The Pragokoncert Agency declined these offers “with thanks” and Bělohlávek had to continue to concentrate on orchestras and concert halls at home. He took it as it was. He did not become drunk on success and emigration was never an option for him. Purposefully and step by step, he aimed at his goal of becoming a true and genuine artist, regardless of competitions, external acclaim or political limits.

…one must distinguish between two things – becoming a winner in a competition on the one hand and becoming a genuine artist on the other – there is no equivalence nor causality between the two. This is especially true about conductors – success in a competition does not directly determine the birth of a true personality of a great conductor, it is solely a key to the opportunity to conduct a world-famous orchestra and grow further with the task.

Our generation went through a time when everybody had to think about where to find their place, a bearable place. I never found a satisfying answer, I had the feeling that I was a Czech who was wounded incurably by the Vltava River and the Prague Castle. Jan Werich once said somewhere: You cannot ever feel at home there where you did not play marbles or kissed for the first time.

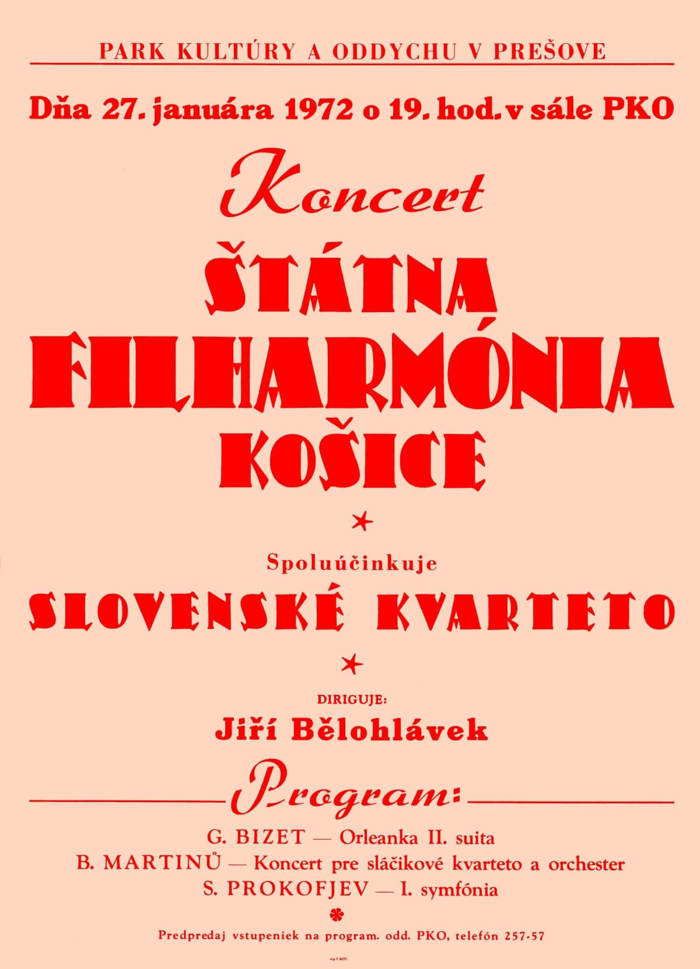

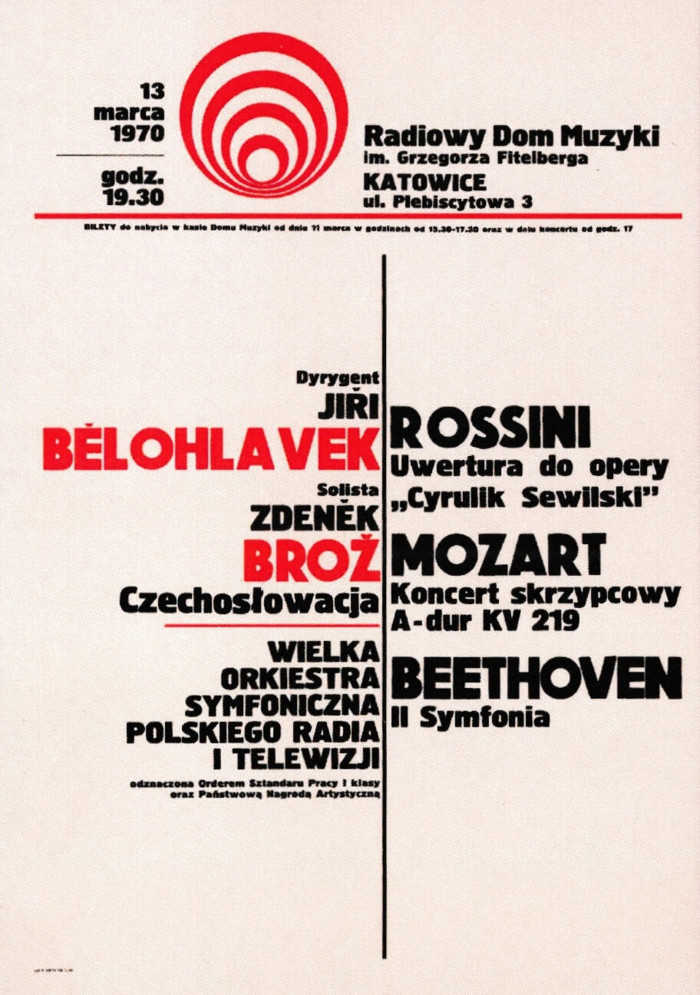

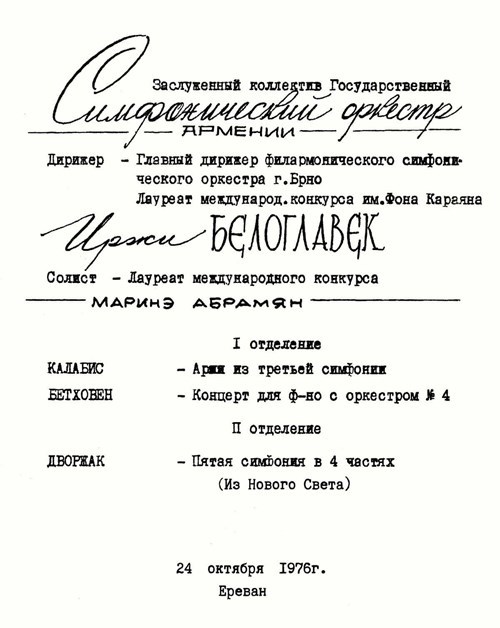

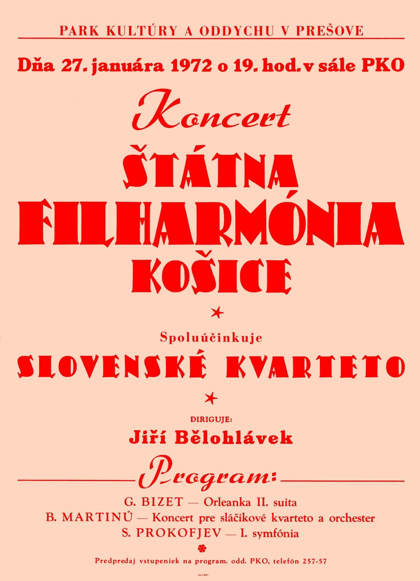

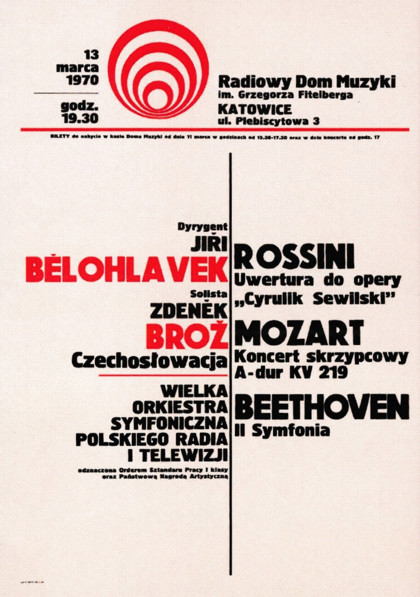

In 1970, 1971 and 1972 Bělohlávek had his debut with other orchestras, some within Czechoslovakia: the Prague Symphony Orchestra FOK, State Philharmonic Orchestra in Brno or State Philharmonic Orchestra Košice; some abroad - The Moscow State Philharmonic Orchestra, the Symphonic Orchestra of the Polish Radio and Television in Katowice, Hallesche Philharmonie in GDR or the Hungarian MÁV Symphony Orchestra Budapest.

The Academy of Performing Arts, AMU, in Prague started the new academic year in September 1972 by a number of graduation concerts. On 25 September, Jiří Bělohlávek conducted a programme of Dvořák, Mozart and Mahler at the Rudolfinum, with the soprano Jana Jonášová and pianist Helena Cinybulková as soloists. The Hudební rozhledy magazine reviewed the concert and informed that the fresh graduate Jiří Bělohlávek “became the second conductor of the State Philharmonic Orchestra Brno on 15 October”. [ 19 ]

The concert confirmed clearly what had been obvious to those following the student’s career in the previous months – Jiří Bělohlávek graduated from AMU as a true creative artist. Not only the audience were left with a deep impression, but even Bělohlávek retained a lasting memory of this concert: “I will never forget my graduation concert, one of my first touches with a really great professional orchestra. I conducted Mahler’s Fourth Symphony with the Prague Symphony Orchestra. And I felt truly happy then.” [ 20 ]

The early 1970s brought another significant debut. After a 7-year-long relationship, Anna Fejérová and Jiří Bělohlávek got married. The wedding took place on 6 February 1971 in Košice.

We got married in 1971 and it was a surprise for everybody including the two of us, as nothing had been said about our wedding before. I had been somehow next to him all the time, I’d lived in a student dormitory and he lived at his parents’. At that time, he was a guest conductor with the State Philharmonic Orchestra in Košice and I took a week’s leave from school to go there with him. We went to the cinema together to see Zeffirelli’s “Romeo and Juliet” and we liked the film wedding very much and then over a glass of Chianti Jiří said: “What if we got married? Arrange the nearest date at the municipal office and I will bring you the white dress from your dormitory.” And that was it.

Main sources

- 1.

Odesilatel: Bureš, Miloslav. Příjemce: Martinů, Bohuslav, rodina v Poličce. Datum odeslání: 11. 12. 1955. Centrum Bohuslava Martinů v Poličce. Available online

- 2.

CÍSAŘ, Jaroslav: Zlatý důl vzpomínek. Život Jana Farmera Obermayera plný hudby. Ústí nad Orlicí: Oftis 2010, s. 26.

- 3.

POKORA, Miloš: Jan Kühn a trvalý otisk jeho sborů v hudebním dění. Praha: Nakladatelství AMU 2017, s. 159.

- 4.

KOLÁČKOVÁ, Yvetta: Jiří Bělohlávek o sobě, rodině a hudbě. Rudolfinum revue 2005/2006, č. 3, s. 24–28.

- 5.

WEISSOVÁ, Lenka: Odvážní začátečníci: Orchestr mladých. Mladá fronta 1961, č. 33 (2. 2., pražské vydání)

- 6.

VÁŇA, Ladislav (scénář a režie): Tenerezza. Filmový dokument. Česká televize 1993.

- 7.

BUDIŠ, Ratibor: Tribuna mladých: Slibný talent. (Rozhovor s Jiřím Bělohlávkem). Hudební rozhledy 1969, č. 11, s. 333.

- 8.

NENUDOVÁ, Hana: My dva spolu nedirigujeme. (Rozhovor s Annou Fejérovou, manželkou Jiřího Bělohlávka). Vlasta 1996, č. 24, s. 11.

- 9.

HRUŠKOVÁ, Milena: Orchestra Puellarum Pragensis. Květy 1968, č. 2, s. 52.

- 10.

BUDIŠ, Ratibor: Tribuna mladých: Slibný talent. (Rozhovor s Jiřím Bělohlávkem). Hudební rozhledy 1969, č. 11, s. 333.

- 11.

VEBER, Petr: Jiří Bělohlávek uvádí v Londýně hodně české hudby. Český rozhlas D-dur. 21. 8. 2008. Available online

- 12.

Hudební mládež a Kruhy přátel hudby. Hudební rozhledy 1969, č. 23–24, s. 769.

- 13.

PANSDORFOVÁ, Eva.: Česká filharmonie s mladými umělci. Hudební rozhledy 1971, č. 12, s. 534.

- 14.

JIRKO, Ivan: Česká filharmonie s Bělohlávkem a Danonem. Hudební rozhledy 1971, č. 6, s. 241.

- 15.

(jj): Zájezd České filharmonie po severních Čechách. Průboj: krajský týdeník KSČ Ústeckého kraje 23, 1971, č. 148 , s. 5.

- 16.

KOLÁČKOVÁ, Yvetta: Jiří Bělohlávek o sobě, rodině a hudbě. Rudolfinum revue 2005/2006, č. 3, s. 24–28.

- 17.

VÍTOVÁ, Eva: Tribuna mladých interpretů. Rozhovor s Jiřím Bělohlávkem. Hudební rozhledy1979, č. 5, s. 234.

- 18.

ŘÍHOVÁ, Klára: Magické ruce. Květy 1998, č. 23, s. 23.

- 19.

Různé zprávy. Hudební rozhledy 25, 1972, č. 11, s. 522.

- 20.

PLAVCOVÁ, Alena: Maestro. Jiří Bělohlávek. Pátek. Magazín Lidových novin 2005, č. 16, s. 4–10.

- 21.

NEKUDOVÁ, Hana: My dva spolu nedirigujeme. (Rozhovor s Annou Fejérovou, manželkou Jiřího Bělohlávka). Vlasta 1996, č. 24, s. 11.

Odesilatel: Bureš, Miloslav. Příjemce: Martinů, Bohuslav, rodina v Poličce. Datum odeslání: 11. 12. 1955. Centrum Bohuslava Martinů v Poličce. Available online

CÍSAŘ, Jaroslav: Zlatý důl vzpomínek. Život Jana Farmera Obermayera plný hudby. Ústí nad Orlicí: Oftis 2010, s. 26.

POKORA, Miloš: Jan Kühn a trvalý otisk jeho sborů v hudebním dění. Praha: Nakladatelství AMU 2017, s. 159.

KOLÁČKOVÁ, Yvetta: Jiří Bělohlávek o sobě, rodině a hudbě. Rudolfinum revue 2005/2006, č. 3, s. 24–28.

WEISSOVÁ, Lenka: Odvážní začátečníci: Orchestr mladých. Mladá fronta 1961, č. 33 (2. 2., pražské vydání)

VÁŇA, Ladislav (scénář a režie): Tenerezza. Filmový dokument. Česká televize 1993.

BUDIŠ, Ratibor: Tribuna mladých: Slibný talent. (Rozhovor s Jiřím Bělohlávkem). Hudební rozhledy 1969, č. 11, s. 333.

NENUDOVÁ, Hana: My dva spolu nedirigujeme. (Rozhovor s Annou Fejérovou, manželkou Jiřího Bělohlávka). Vlasta 1996, č. 24, s. 11.

HRUŠKOVÁ, Milena: Orchestra Puellarum Pragensis. Květy 1968, č. 2, s. 52.

BUDIŠ, Ratibor: Tribuna mladých: Slibný talent. (Rozhovor s Jiřím Bělohlávkem). Hudební rozhledy 1969, č. 11, s. 333.

VEBER, Petr: Jiří Bělohlávek uvádí v Londýně hodně české hudby. Český rozhlas D-dur. 21. 8. 2008. Available online

Hudební mládež a Kruhy přátel hudby. Hudební rozhledy 1969, č. 23–24, s. 769.

PANSDORFOVÁ, Eva.: Česká filharmonie s mladými umělci. Hudební rozhledy 1971, č. 12, s. 534.

JIRKO, Ivan: Česká filharmonie s Bělohlávkem a Danonem. Hudební rozhledy 1971, č. 6, s. 241.

(jj): Zájezd České filharmonie po severních Čechách. Průboj: krajský týdeník KSČ Ústeckého kraje 23, 1971, č. 148 , s. 5.

KOLÁČKOVÁ, Yvetta: Jiří Bělohlávek o sobě, rodině a hudbě. Rudolfinum revue 2005/2006, č. 3, s. 24–28.

VÍTOVÁ, Eva: Tribuna mladých interpretů. Rozhovor s Jiřím Bělohlávkem. Hudební rozhledy1979, č. 5, s. 234.

ŘÍHOVÁ, Klára: Magické ruce. Květy 1998, č. 23, s. 23.

Různé zprávy. Hudební rozhledy 25, 1972, č. 11, s. 522.

PLAVCOVÁ, Alena: Maestro. Jiří Bělohlávek. Pátek. Magazín Lidových novin 2005, č. 16, s. 4–10.

NEKUDOVÁ, Hana: My dva spolu nedirigujeme. (Rozhovor s Annou Fejérovou, manželkou Jiřího Bělohlávka). Vlasta 1996, č. 24, s. 11.