The twelve years that I was Music Director and Chief Conductor with the Prague Symphony Orchestra were a very happy time of my life. It was a time of constant falling in and out of favour of external circumstances and of momentous events, but it was also a time that made me very happy as I found a wonderful group of people with whom we worked on our common cause.

There was a change on the post of the chief conductor of The Prague Symphony Orchestra FOK already in 1972 when after three decades on the post, Václav Smetáček retired. Already back then, Bělohlávek was a real option [ 2 ],but in the end the managers gave preference to Ladislav Slovák, who was older and more experienced and the chief conductor of the Slovak Philharmonic at the time. Slovák, however, returned to Slovakia after four seasons and the new director, Ladislav Šíp, had to face his first challenge – to find a new and stable music director.

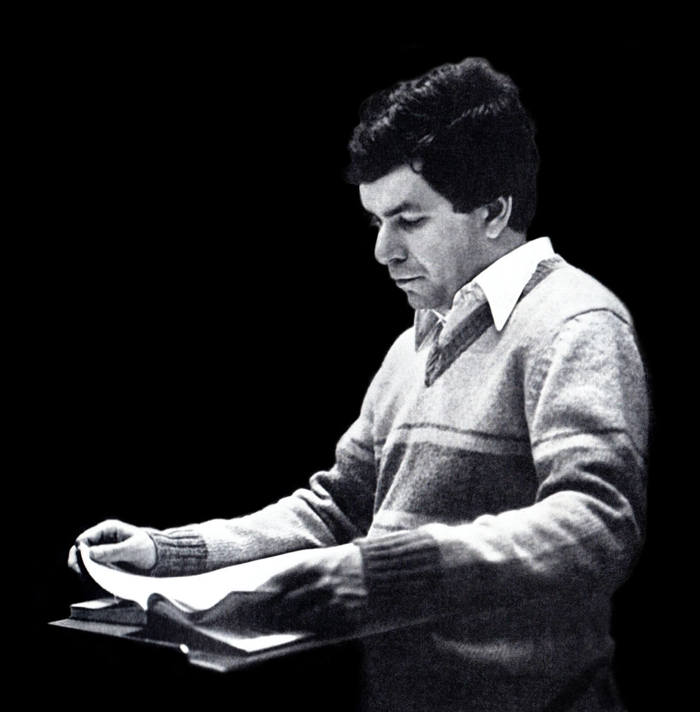

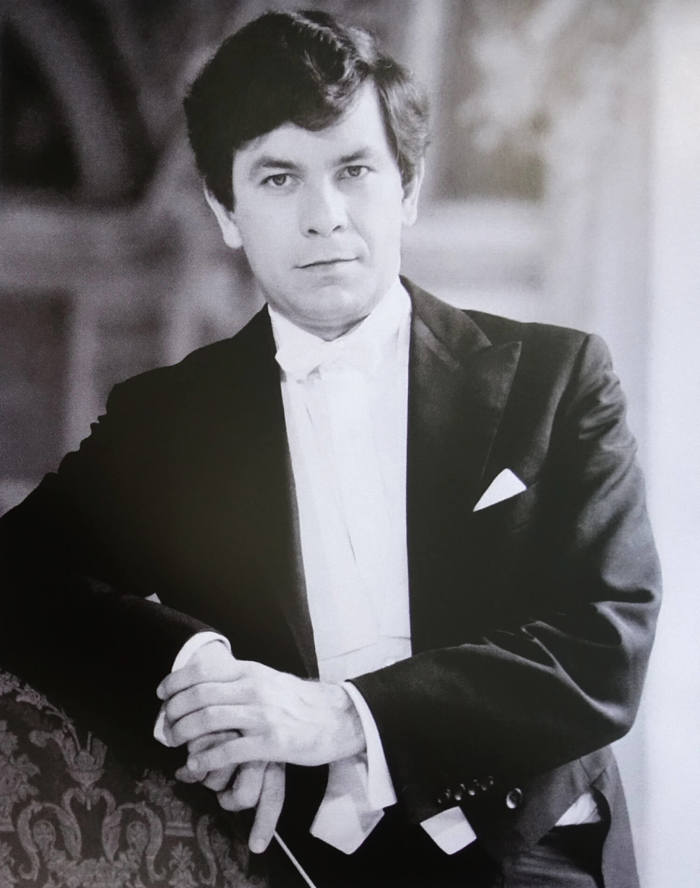

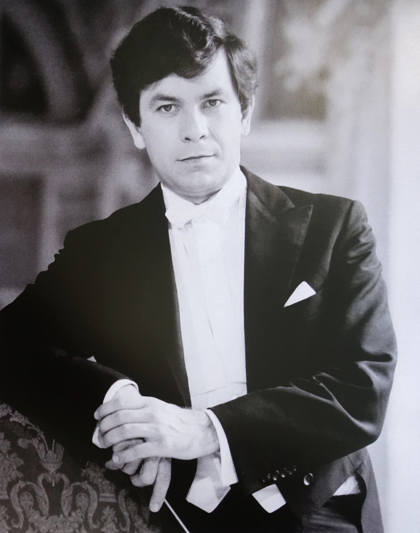

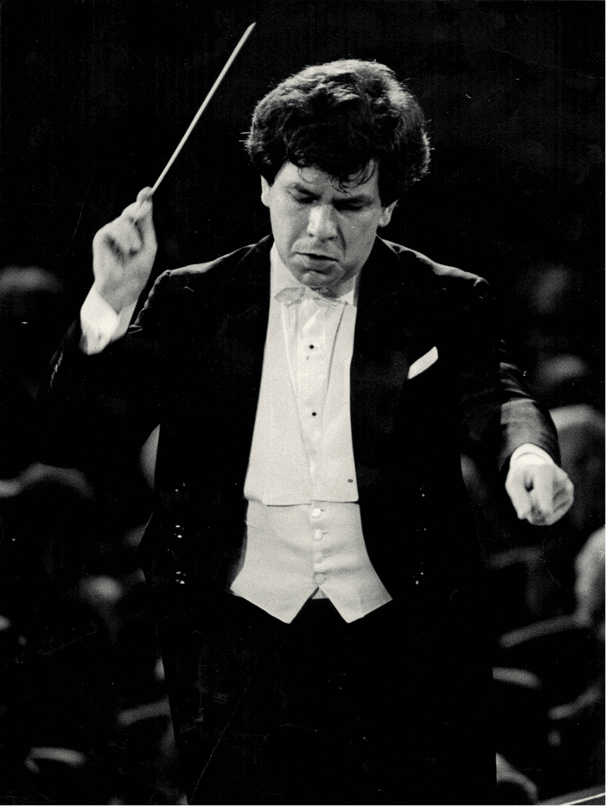

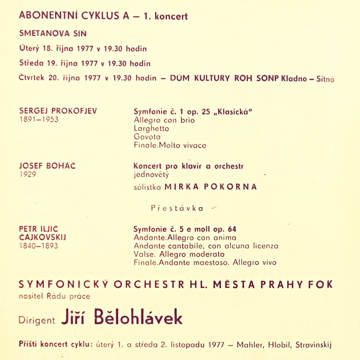

And thus in 1976 Jiří Bělohlávek got the offer to become the music director of the Prague Symphony Orchestra. The offer soon changed – maybe as a result of lingering fears over the conductor’s youth – to only a conducting position with a long-term prospect of becoming the chief conductor. However, Bělohlávek was sure of his abilities and plans. Later he remembered that he’d sent “a polite but decisive letter” describing his ambitious vision of the orchestra’s development that can be realized only from the music director’s position. [ 3 ]His determination and self-confidence must have made an impression on Šíp and his colleagues and Bělohlávek was appointed the music director of the Prague Symphony Orchestra effective from 1 September 1977.

Before he began, he chose a second conductor. Vladimír Válek, whose spontaneous musicality complemented Bělohlávek’s intellectual approach to conducting, was chosen from the potential candidates. After Válek left to take up a position with the Czechoslovak Radio Symphony Orchestra in 1987, Petr Altrichter, who would later become the chief conductor of the Prague Symphony, took over his position. A third conductor sometimes complemented the permanent conducting pair. In the 1980s it was the young Hynek Farkač – making it the youngest group of conductors any professional Czechoslovak ensemble had at the time.

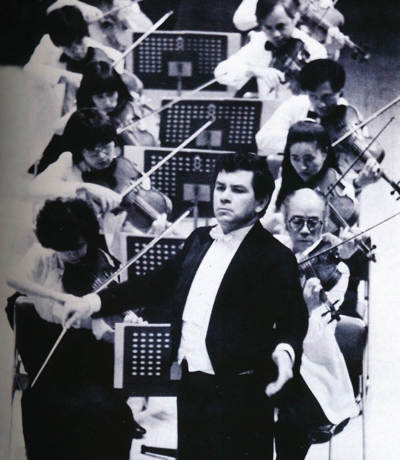

The first night was a major event for the ensemble, too, as it brought its previous successful development onto a higher level of demanding artistic collaboration. . (…) Under Bělohlávek’s baton, the evening’s highlight in terms of interpretation was Tchaikovsky’s “Fifth Symphony in e minor.” Bělohlávek conducted this monumental autobiographical fresco by heart and with extraordinary certainty and command. Widely arched wholes of the symphony’s movements together with minutely crafted details created a compelling dramatic musical flow. The conductor’s and the orchestra’s performance were penetrated by a distinctly creative atmosphere in which extraordinary interpretation could flourish. (…) First impressions and outcomes of this artistic collaboration already show a promising, mutually beneficial and successful journey ahead.

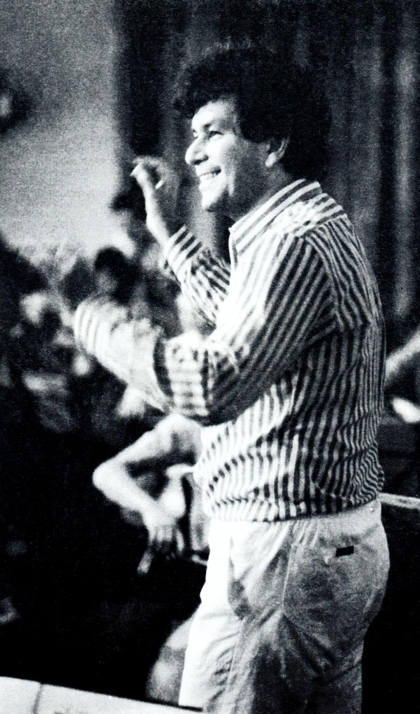

Diligent work with the orchestra began on an almost daily basis: “Jiří Bělohlávek assumed his duties with imposing energy and enthusiasm. Soon after he started, he made some changes in the seating of orchestra players and started to take care of technical details of the orchestra’s life intensively and consistently. He contributed actively to dramaturgic plans and dealt with social, economic and legal issues – in short, he fulfilled his role fully in all of its aspects.” [ 5 ]

Bělohlávek’s consistent approach to rehearsing is remembered by FOK’s first clarinetist Vlastimil Mareš.

…the chief conductor could put every second to good use. And he still can. He does not waste time. Each minute has its unrepeatable value and must be used accordingly. He used time in the same way as the grandmother from Němcová’s novel used breadcrumbs – not a single crumb could be wasted. When the players impatiently looked towards the door and were restless on their chairs at the end of a rehearsal, he would say: “We still have two more minutes left in this wonderful hall, it would be a disgrace to leave such unique acoustics too early.” And he did not lose the two minutes.

The first fruit of hard work soon came in the form of various successes and awards and the orchestra was soon perceived as an ensemble of equal in its quality to the Czech Philharmonic. The reputation spread not only at home, but also internationally. Bělohlávek and the FOK went on many successful tours abroad together: the Netherlands and Belgium in 1978; Spain, GDR, Austria and Germany in 1979; the UK in February and March 1980 and the Montreux festival in Switzerland in September of the same year.

… the concert of the Prague Symphony Orchestra was a major musical experience. From the very first bars of Mahler’s First Symphony “Titan”, the conductor Jiří Bělohlávek led us into the centre of “beauty”. This work by the master of exulting musical connections and the genius of bright colours was conducted by the ensemble’s chief conductor in an engrossing and astonishing manner – from the first to the last bar.

The autumn of 1982 was a very busy time for the Prague Symphonic Orchestra. Under the management of its director Ladislav Šíp and together with both its conductors, Jiří Bělohlávek and Vladimír Válek, they made an extensive tour of Germany, including concerts in Munich, Nürnberg and Frankfurt. A tour of the USA with twenty-nine concerts in thirty-eight days followed immediately and included performances at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., at Carnegie Hall in New York or the Grand Opera in Macon. Some orchestra members also took up the role of soloists – the first cellist Miroslav Petráš and also Vladislav Kozderka (trumpet). The American violinist Eugene Fodor was the soloist at three of the concerts.

One of the striking aspects of Dvorak's ''New World'' Symphony (Op. 95) played Wednesday by the Prague Symphony Orchestra in Carnegie Hall was that the music mattered. It was not played as a sonic showpiece or as a collection of melodies. Dvorak, after all, died in the orchestra's native city; the orchestra's music director, Jiri Belohlavek, was bearing the symphony from the Old World to the New. (…) …the symphony was played with a personal warmth and graciousness. Instrumental balances were carefully controlled, yet climaxes were expansive; melodies were sweetly sung without sounding sentimental. The work's innocent, folksy freedom was integrated with the European classical tradition; the orchestra did not have to pretend to either.

The afternoon was one of unalloyed pleasure leaving me breathless with admiration. The orchestra, as befits one of the great musical capitals of Europe, was revealed as an ensemble that is as near perfection as one can hear today.

The tour’s success was testified by many positive reviews and reactions of the American agency which, straight after the tour concluded, commissioned another tour of the orchestra for autumn 1985, offering overall much better financial conditions. The 1985 US tour was regarded as the most successful to date. Moreover, it reaped a personal reward for the chief conductor who was offered to conduct five concerts with the New York Philharmonic. Only two Czech conductors had led this orchestra before: Zdeněk Košler and Václav Neumann.

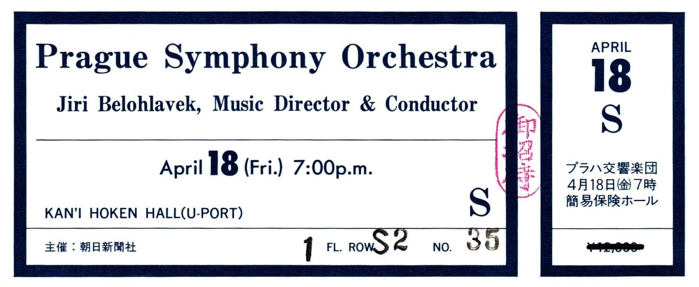

The first tour to Japan took place in April 1986. The orchestra played seven concerts there – three in Tokyo and four in Osaka. At the organisers’ request, the orchestra performed Gustav Mahler, whose music had grown very close to the players’ hearts, thanks to Jiří Bělohlávek, and also compositions by Bohuslav Martinů, Bedřich Smetana, Antonín Dvořák and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. The tour was crowned by a concert at the Osaka International Festival. The orchestra’s performances were received enthusiastically and reviewed with superlatives.

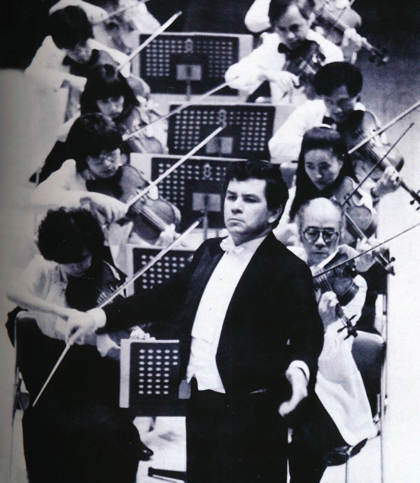

During the 1970s and 1980s, Bělohlávek also went on international expeditions independently. Japan was a popular stop on his conducting journeys around the world. He would return regularly to orchestras residing in Tokyo, especially to the Japan Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra. He introduced Czech music to Japanese orchestras and audiences - Janáček’s Sinfonietta or Bohuslav Martinů’s symphonies – and together with other Czech conductors he helped to extend the Czech repertoire spectrum in the country. With orchestras prepared perfectly in technical terms, Bělohlávek worked especially on the emotional dimension of the performed pieces.

Japanese orchestras are on an excellent technical level, incredibly disciplined and eager. However, I cannot count on their own emotional input in the interpretation. One needs to build up the expressive world with them step by step, to recast the content of the work somehow and bring it closer to them.

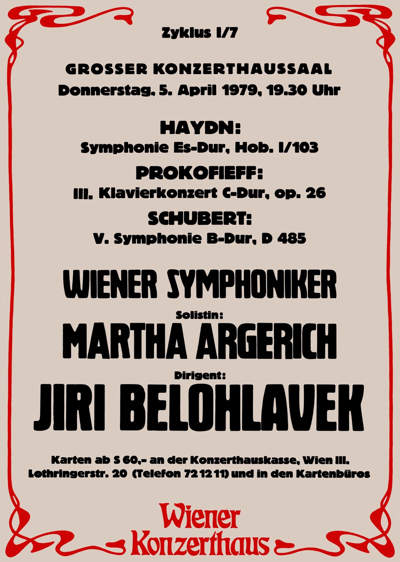

Bělohlávek’s other musical destinations at the time included Vienna in 1979, where, together with the pianist Martha Argerich and the Vienna Symphony Orchestra, he performed the works of Joseph Haydn, Sergey Prokofiev, and Franz Schubert. In 1982 he went to Canada to conduct the Toronto Symphony Orchestra with which he performed Dvořák. His collaboration with the orchestra continued in the following years and focused especially on various works of Czech composers. Still in 1982, he conducted the Presidential Symphony Orchestra in Ankara in a programme of Bedřich Smetana and Antonín Dvořák. He often collaborated with the Dresden Philharmonic Orchestra, with which the Prague Symphony Orchestra had a partnership, a partnership so profound that Bělohlávek even made a tour of Spain with the German orchestra in August 1982. In the 1984/1985 season, Bělohlávek was a guest conductor with the New York Philharmonic and conducted compositions by Bartók, Beethoven and Dvořák.

The year 1984 was celebrated as The Year of Czech Music, both on stages in Czechoslovakia and at festivals abroad. A Czech trace was prominent at the international music festival in Luzern that presented a large range of Czech music from pre-Hussite chants, Rychnovský, Vejvanovský, Michna, Zelenka to the great four - Smetana, Dvořák, Janáček and Martinů. Contemporary music was also included, e.g. works by Petr Eben. The opening and final nights consisting solely of Czech symphonic programmes highlighted the Czech focus.

Bělohlávek drew attention to himself at the opening night, which was dedicated solely to works of Bohuslav Martinů (the Double Concerto for String Orchestra, Piano and Timpani with Rudolf Firkušný on the piano, Field Mass and the Fourth Symphony) not only due to his art of interpretation, but also due to his ability to conduct the concert at short notice, standing in for Rafael Kubelík, who was ill (his identity, however, was not disclosed by the Czechoslovak press), and thus saving the evening successfully. Bělohlávek was invited to the festival the following year as well, most likely because of this successful concert. The final night was performed by Rafael Kubelík, recovered by that time, and the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. Smetana’s Má vlast was on the programme.

Bělohlávek had his debut with the Berliner Philharmoniker in February 1986, the programme included Janáček’s Sinfonietta. In July of the same year, he returned to the USA to conduct the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra and the Detroit Symphony Orchestra at summer festivals. Later in 1988 he conducted Smetana’s Má vlast with the Boston Symphony Orchestra at the Tanglewood Music Festival. And this list could go on and on, every year debuts with new ensembles and reappearances with the old ones.

Bělohlávek naturally devoted his time to Czechoslovak orchestras, too. He collaborated intensively with the Czech Philharmonic, in 1981 became its permanent conductor and often conducted the subscription concerts at the Rudolfinum. Every now and then, he would even conduct the Czech Philharmonic and the Prague Symphony Orchestra within the same week. Bělohlávek took an active role in the popular Czech Philharmonic for the Young cycle, appearing also on TV. The ten episodes filmed between 1986 and 1988 followed up from the popular programme broadcast between 1974 and 1980 called The Czech Philharmonic Plays and Talks with the conductor Václav Neumann. The aim of the programme was to talk about “connections between music, love, jazz, visual arts, war and peace. It focused also on orchestral and soloistic virtuosity, Mozart’s Prague, Ludwig van Beethoven or Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring.” [ 13 ]Bělohlávek took the Czech Philharmonic on tours abroad, to the USA in 1984 and 1987 to name but two, and made many recordings. His complete recording of orchestral works by Brahms from the late 1980s and early 1990s won him great acclaim. And one of important premieres – conducting the opening concert of the Prague Spring Festival – was also with the Czech Philharmonic.

Bělohlávek appeared several times at the festival also with the Prague Symphony Orchestra. On 2 June 1984 he conducted Mahler and Dvořák in a concert which was also a celebration of the ensemble’s fiftieth anniversary. Further, he performed with the orchestra at Smetana’s Litomyšl and Stříbro Music Summer festivals. Concerts at the latter event took place in the majestic Church of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary in Kladruby.

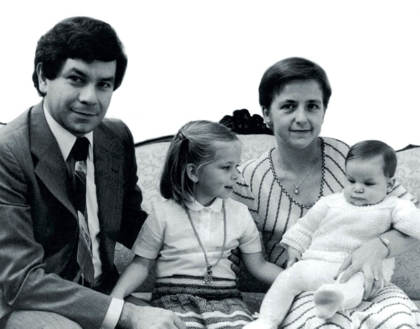

In Bělohlávek’s personal life, important events also happened at this time - the birth of his second daughter, Marie, in 1981 was probably at the top. The well-known saying that behind every successful man there was a strong woman was true in the Bělohlávek family, too. Not only that Bělohlávek’s wife Anna took care of the whole family and took over most of the responsibilities each and every day, but she also had an understanding for complexities and time-consuming nature of a conductor’s work, being a trained and experienced concert musician herself. Throughout their life together, she was his knowledgeable advisor, sincere critic and loving and supporting partner.

I have no ambition of a conductor’s wife to be telling everybody how it was when we conducted in New York last year … I don’t conduct with him, my place in his life is elsewhere. Whenever I can, I try to be there at his concerts, performances and sometimes even rehearsals, as I find it extremely important to follow his work. I love to talk about my impressions of theatre, films, books, but most of all I love to experience something beautiful together with him.

The fact that he was a married man with two children helped in respect of his collaboration abroad, as the probability of emigration in such cases was minimal. On the other hand, Bělohlávek’s mastery and success were highly visible and opened paths for him to positions at the top, and there political engagement and loyalty to the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia were expected and required. Bělohlávek tried and managed to avoid becoming a member of the party, and when, for the benefit of the whole family, he was sometimes in doubt, his wife intervened.

When I was the music director of the FOK orchestra, my bosses kept attacking me with offers of party membership. It was a strict condition for people in higher positions, such as music directors. I was an exception that director Šíp had to strive to justify every year. It was a paradox that only when the pressures weakened, I started to feel that without the party’s support I cannot act strongly enough in the orchestra’s interest and that through insisting on my freedom I do the ensemble harm. I began to flirt with the idea of accepting the Communist party membership card… My wife looked at me then and said: “Have you gone mad? You would lose yourself!” She opened my eyes and I realized I would sell out my soul in this way – and that is how I resisted. Until this day I have been enormously grateful to her for this, it is one of the strong bonds between the two of us.

Political issues, however, were not the only complications the chief conductor had to face. The orchestra had problems with regard to the music hall where it was at home – the Art Nouveau building of the Municipal House in Prague. The building had not been renovated and repaired since the time it was built. In the 1970s, the Smetana Hall with the backstage area and offices could no longer support the intensive concert life of the building where, besides the home orchestra, many other ensembles, small and large, performed. Frequent interventions of the director and the chief conductor with the Prague City Hall and the Ministry of Culture resulted only in minor “patches”. The Municipal House had to wait until 1994 before the general reconstruction, which lasted until 1997, began.

When I was the music director of the FOK, I lived three minutes away from the Smetana Hall. At that time, I used to do a crazy thing that I would leave home exactly three minutes before a rehearsal or a concert was due to start. And I delighted in the fact that everyone was in suspense whether I’d turn up or not. Today, it would make me terribly nervous, and I am glad to arrive at the venue ahead of time.

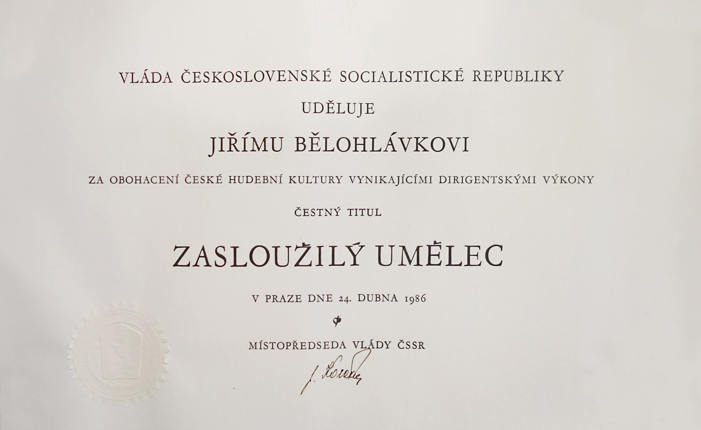

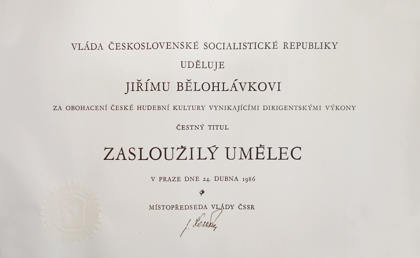

In 1986 Bělohlávek celebrated his fortieth birthday and was appreciated both professionally and personally. In February he got beautiful birthday cards from his daughters Zuzana and Marie and in May he received the Distinguished Master of Arts title from the government. Bělohlávek was awarded this title especially for his long-term and diligent work with the FOK Orchestra which had reached a high artistic level under his leadership.

In 1987, Bělohlávek took part in a project entitled The International Youth Philharmonic Orchestra initiated by the Czechoslovak Ministry of Culture. Together with his assistant Bohumil Kulínský he prepared and conducted a concert tour of an orchestra composed of one hundred and twenty young musicians from six socialist states. Sixty Czechoslovak, twenty Soviet, ten Bulgarian, ten Hungarian, ten East German and ten Polish students of conservatoires and music academies first had a fortnight of intensive rehearsing in July in Mariánské Lázně and a week in Prague later in October. The first concert of the tour was on 30 October 1987 in the Smetana Hall in the Municipal House in Prague, with a programme of Beethoven, Dvořák and Shostakovich. Later they performed in Berlin, Warsaw, Moscow, Sofia and Budapest. The closing night of the tour was held in Reduta in Bratislava. Bělohlávek thus gained his first major experience with conducting very young musicians. Although slightly sceptical at the start, he was pleased after the first rehearsals, and he learned how working with enthusiastic and motivated young people can be creative and evolve rapidly. Such an experience surely boosted his interest in projects and activities with young musicians: his founding of The PKF - Prague Philharmonia in 1994, performing Má vlast at the opening concert of the Prague Spring Festival 2011 with the orchestra of the Prague Conservatoire and other projects.

Maybe it is the step into the unknown that has attracted me so much. Nothing is certain here, something is being born and it is great to be part of it. (…) What I witnessed was a small miracle, I would have never believed that it is possible to create such a uniting bond within a group of musicians, moreover musicians who have so little experience…

Bělohlávek held the position of chief conductor of the FOK for twelve years, which was the longest lasting chief conductor post he ever had. For him, it was a period in which he built up, thanks to his focused and systematic work, his impressively large repertoire, and in which he deepened his approaches to interpretation of already studied compositions. He deliberately chose challenging tasks which enabled him and the orchestra to grow artistically and to refine their mastery. One such mission consisted of the works of Gustav Mahler which Bělohlávek included in the orchestra’s concert programmes since the early 1980s. Following initial uncertainties, the conductor and the players fathomed the specific nature of Mahler’s musical language and with the works of this master born in Kaliště created many great musical experiences for the audiences at home and abroad. Another such example was the work of Bohuslav Martinů which was performed in entirety including early compositions such as Czech Rhapsody (1918).

The First Symphony has matured with the Prague Symphony Orchestra and it was obvious at this concert that the longer process reaped success. After mastering Janáček, Jiří Bělohlávek has succeeded in getting to the core of the composer’s message in the case of Bohuslav Martinů and, most importantly, in inspiring the orchestra to follow and implement his interpretation ideas. (…) Idioms of Czech musicality radiated from Bělohlávek’s interpretation. The orchestra literally breathed with the conductor and performed the piece with extraordinary vividness.

When drawing up the concert plans for each season, it was, on the one hand, necessary to make concessions to the regime’s requirements of including a committed composition by an average Soviet composer or to premiere a contemporary Czechoslovak piece dictated by the Composers’ Union; on the other hand, however, it was possible to include also spiritual and Christian compositions (e.g. Martinů’s Miracles of Mary). Because it was politically unproblematic, Bělohlávek and the FOK orchestra played the works of many Russian composers such as Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninov, Prokofiev and Shostakovich, or Czech composers such as Dvořák, Smetana, Janáček, Josef Suk and, very intensively, Bohuslav Martinů. In addition to famous works of Czech musical literature, he also studied and performed lesser-known and neglected compositions, including those of Czech contemporary authors. In 1986, for instance, he performed Vladimír Sommer’s Vocal Symphony with the FOK. For this, Bělohlávek invited a young alto Dagmar Pecková, for whom it was a debut at the Smetana Hall.

After Zdeněk Košler’s condemnation, Jiří Bělohlávek was the first one who invited me to work with him. It was for Sommer’s “Vocal Symphony” with the FOK orchestra. Back in 1986! Since then, we have worked together regularly. He introduced me to interpreting Mahler, we recorded beautiful CDs together and collaborated on the production of “Carmen” at the National Theatre. I had my debut at many international festivals only thanks to his initiative.

Many of the performances are preserved on media. Bělohlávek’s recordings with the Prague Symphony Orchestra give us an original look into Czech classical music of the late nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century, including works only rarely performed on stage – for example Ostrčil’s Symphony in A major and Symfonieta (1980 and 1983 recording) or Martinů’s monumental vocal work Epos of Gilgamesh (recorded in 1976, reissued in 2007).

When reviewing FOK’s performance at the 25th Bratislava Music Festival, which took place in September and October 1989, the music critic Terézie Ursínová understood precisely the fundamental change that the orchestra had gone through under Jiří Bělohlávek.

Bělohlávek as chief conductor managed to create an orchestra of refined sound culture, typical for “the Czech violin”, of perfectly coordinated playing (Ravel’s “Ma mère l'Oye” was unforgettable) and exploratory projects…

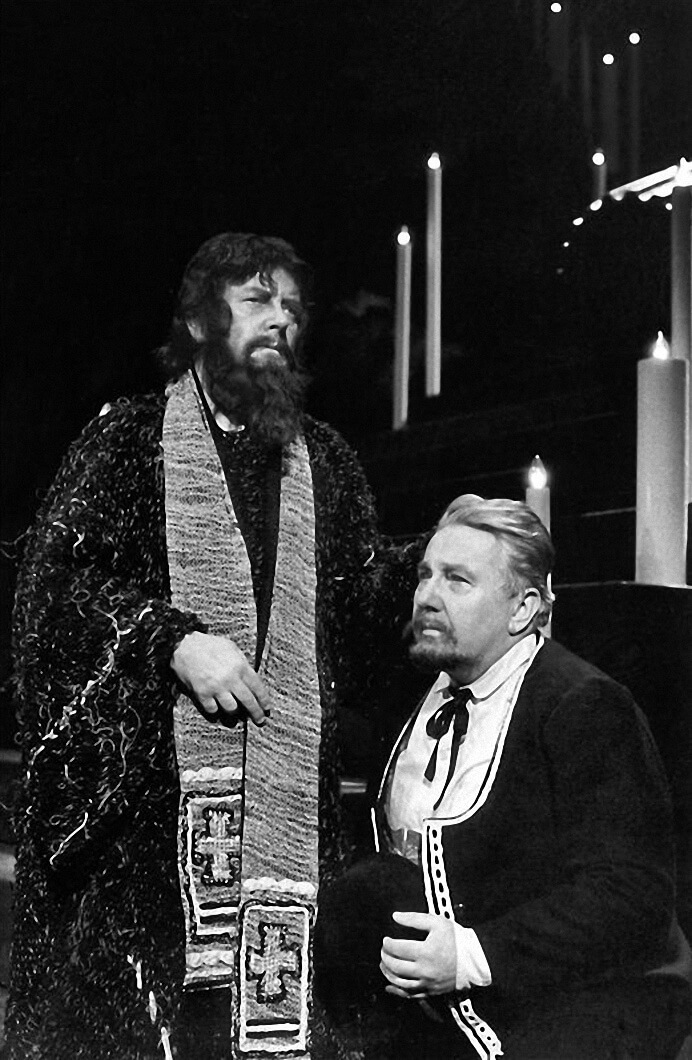

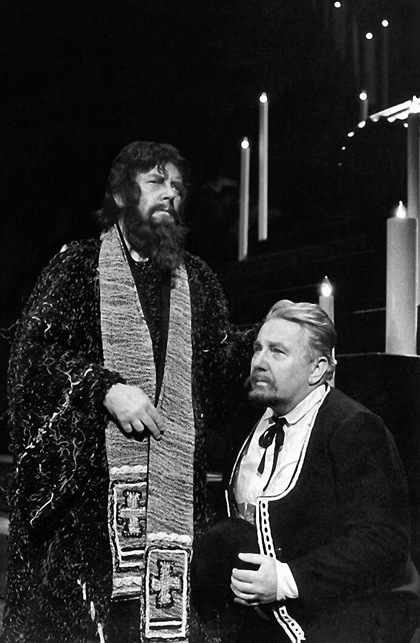

Bělohlávek’s career as an opera conductor developed gradually while he held the position at FOK. Bělohlávek drew from his experience at the Vinohrady Theatre and from his student years at the Academy of Performing Arts where hehad studied Mozart’s Così fan tutte, Don Giovanni, and also The Marriage of Figaro, which he even performed with student singers and the orchestra of the Smetana Theatre (nowadays The State Opera Praha) in 1972. In 1977 he assisted Václav Neumann at the Berlin Comic Opera for the performance of Bedřich Smetana’s Secret.

Bělohlávek worked with the orchestra in the preparatory period, Neumann took over a week prior to the premiere and conducted the first performance. Afterwards Bělohlávek rehearsed with the alternate cast and conducted the second premiere, which I heard. Bělohlávek’s opera debut was very successful. The symphonic dimensions of the score probably motivated him to detailed collaboration with the orchestra which played our music satisfactorily without ever ceasing to accompany, which is crucial in the Comic opera (and elsewhere). (…) Bělohlávek feels Smetana’s lyricism, and he showed absolute technical confidence as one could notice in the second act where he did not let a soloist’s incorrect entrance to upset the whole large ensemble.

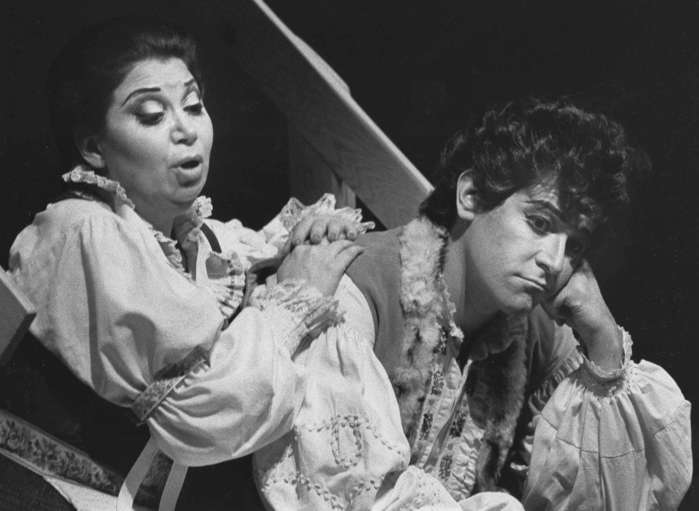

As a result of his success in Berlin, Bělohlávek was invited once again to study and perform The Rake’s Progress by Igor Stravinsky two years later (1979). In Czechoslovakia, his opera debut waited until the 1984 production of Bohuslav Martinů’s Greek Passion at the State Opera in Prague. The crucial year in Bělohlávek’s international opera career was 1985 when he, together with Stephen Wadsworth, made a very well received production of Janáček’s Jenůfa in Seattle in the US.

Bělohlávek immediately hit the bull's-eye, understanding the work and the singers. Under his direction, Bohuslav Martinů’s operatic epilogue was performed with amazing tenderness and emotional depth, he achieved almost chamber-like atmosphere without ever giving up on the dramatic suspense…

To protect Janacek’s interests in the pit, Jenkins engaged Jiri Belohlavek, a young conductor from Prague. It turned out to be a wise choice. Belohlavek made his excellent orchestra, composed of members of the Seattle Symphony, brood and soar and shimmer with dramatic sensitivity. He also gave his singers ardent support, even mouthing the strange English text in sympathy.

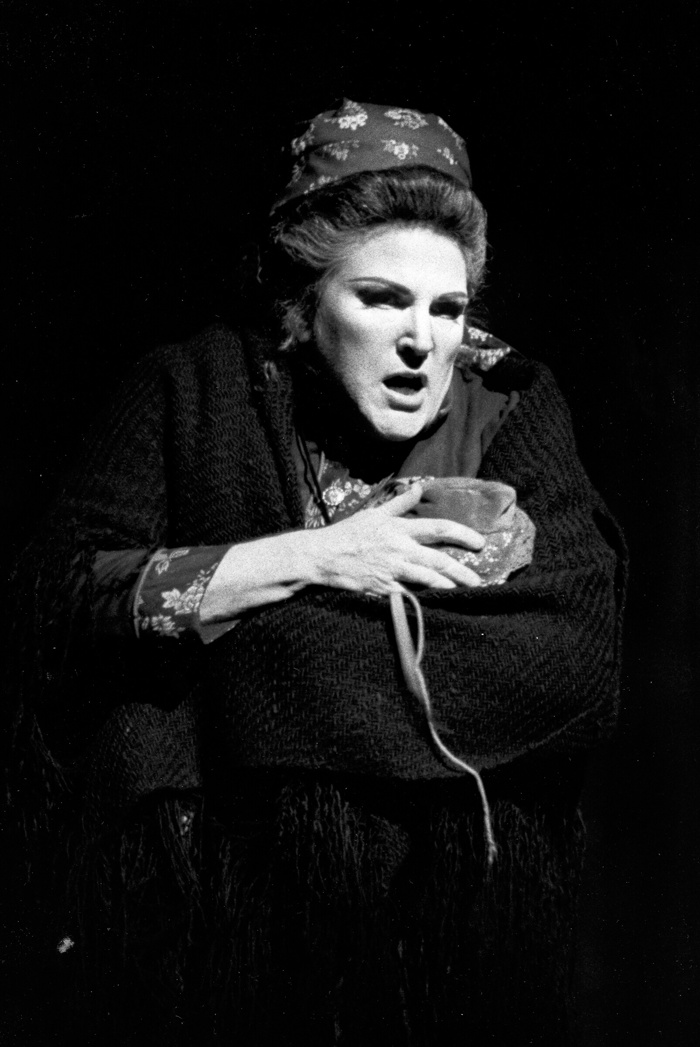

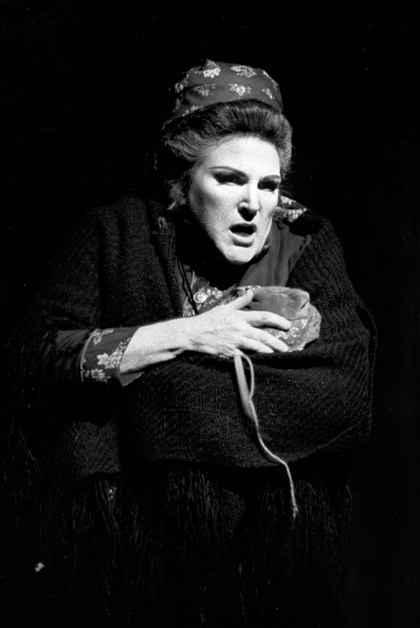

Since the early-1980s, Bělohlávek participated not only in classical opera productions that put together music, drama and stage design, but also in concert performances of operas that omit the dramatic dimension. Bělohlávek began with such projects by a concert performance of B. Martinů’s Miracles of Mary. Together with the Prague Symphony Orchestra, the Czechoslovak Radio Choir, the children’s choir Bambini di Praga and soloists Eva Děpoltová, Anna Bárová, Václav Zítek, Ivan Kusnjer and others, Bělohlávek performed it in the Smetana Hall at the Municipal House and justified thus very successfully this kind of production. Bělohlávek recorded the opera for Supraphon with the same cast (released in 1985).

Bělohlávek built up the whole work using adequate proportions of musical and dynamic climaxes: His extraordinary musicality put the two miracles “Mary of Nijmegen” and “Sister Pasqualina” to full dramatic intensity and powerfully contrasting dynamic gradation, while in the “Nativity of Our Lord” it created a magically poetic pastoral.

Since the 1990s, concert performances became a regular and sought-after presentation form for Bělohlávek. Firstly, the form enabled him to introduce audiences to less common Czech operas, and secondly, operas were thus presented in a pure form, without the risk of being misinterpreted and deformed by unsuitable stage direction and design, as has recently often been the case in opera houses around the world.

Bělohlávek and the Prague Symphony Orchestra participated in another extraordinary opera event. In 1981, they recorded the music for Otmar Mácha’s TV opera The Metamorphoses of Prometheus, based on the libretto of Jiří Kolařík. The music drama had been commissioned by the Czechoslovak Television and was broadcast on 4 October 1982 for the first time. The production was awarded the second prize at the prestigious international competition of music programmes for TV in Salzburg in 1983 and was also awarded the main prize at the Golden Prague International Television Festival in the same year.

The last three months of 1989. In October, Bělohlávek went on a large tour of Western Europe, including Austria, Switzerland, Germany and France, with the Czech Philharmonic. During the tour, while in Switzerland, they learned about the political protest of the orchestra’s chief conductor Václav Neumann who decided to support the signatories of the “Několik vět” (Several Sentences) petition and who declared publicly that he suspended any further collaboration with the Czechoslovak Television until actors and artists who had signed the petition were allowed to work again. The orchestra and the conductors joined Václav Neumann in the proclamation and, moreover, boycotted the Czechoslovak Radio which also suspended Several Sentences signatories from the broadcast.

Having returned from the tour, members of the Czech Philharmonic decided to make their stance known to their audiences. They inserted a leaflet in the programme notes for the concerts of 16 and 17 November 1989 in which they proclaimed their boycott of the radio and television. These concerts were conducted by Jiří Bělohlávek. Those present at the concert on 17 November had no idea that on the very evening, only a couple of hundred metres away from the Municipal House, the venue of the concert, the old regime was just beginning to collapse.

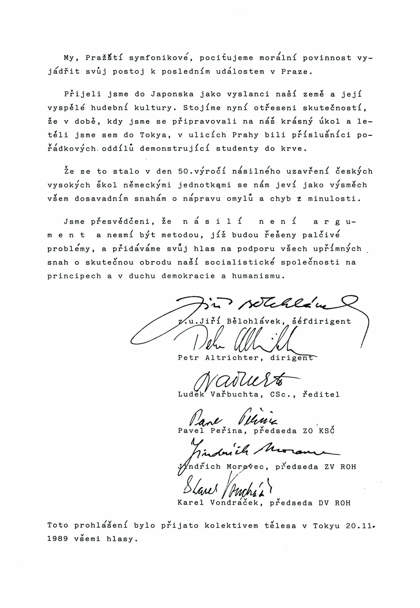

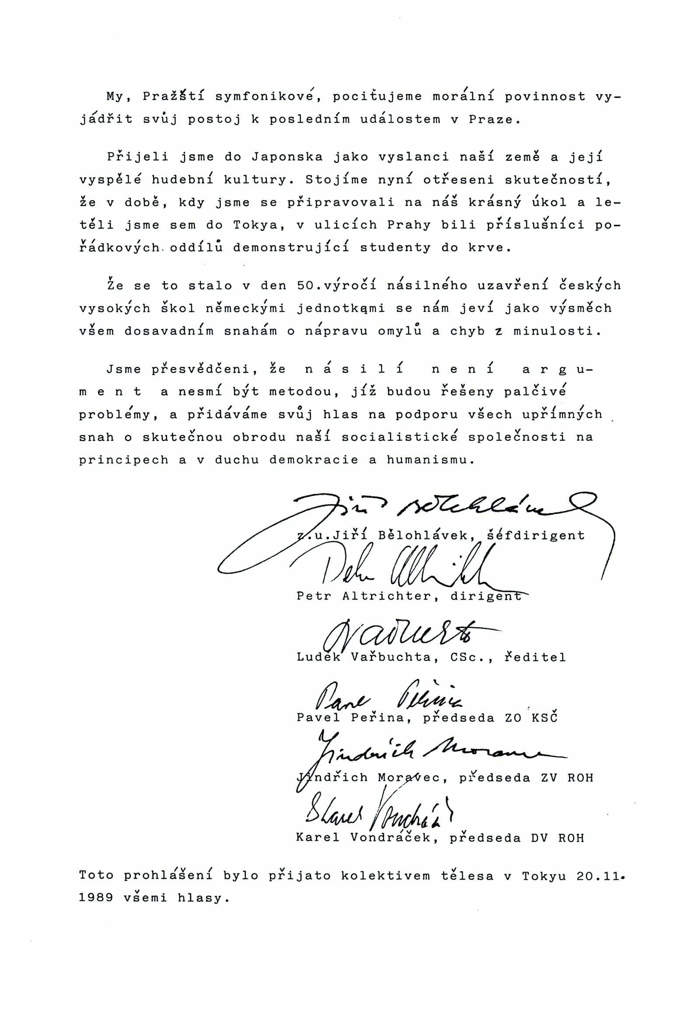

Immediately after these concerts on 18 November, Bělohlávek went on a major tour of Japan, Korea and Taiwan with the Prague Symphony Orchestra. There they learned about the brutal attack of the State Security against students on Národní třída in Prague and they published a joint proclamation. They experienced a very emotional performance of Má vlast in Tokyo, when before the concert Bělohlávek addressed the audience saying that they wanted to dedicate the music to the process of political renewal at home: “In this way, the whole performance transformed from a purely musical to a general, political and national experience. I know for sure that the orchestra players had tears in their eyes.” [ 25 ]

A joint proclamation of the members of the Prague Symphonic Orchestra regarding the events on Národní třída

Translation: We, the members of the Prague Symphony Orchestra, feel morally obliged to express our stance on the latest events in Prague.

We came to Japan as ambassadors of our country and its high musical culture. Now we stand here shaken that at the very time when we were preparing for our beautiful task and were on the plane to Tokyo, the police were brutally beating demonstrating students in the streets of Prague.

The fact that it happened fifty years to date after German army units forcibly closed down Czech universities seems to ridicule all efforts to make up for blunders and errors of the past.

We are deeply convinced that violence is never an argument and must not be used as a method of solving acute problems and we raise our voice in order to support all sincere attempts to renew our socialist society on the principles of democracy and humanism.

This proclamation was accepted by all members of the orchestra on 20 November 1989 in Tokyo

Events at home developed rapidly. Prime Minister Miloš Jakeš resigned along with the entire leadership of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. On 10 December President Gustáv Husák appointed the first not entirely communist government since February 1948 and announced his resignation to the Federal Assembly. On 29 December 1989, Václav Havel was elected President of Czechoslovakia in the Vladislav Hall of Prague Castle. In June 1990, the first democratic elections since 1946 were held, leading to a non-communist government.

These were the months of enthusiasm and general optimism. People were full of hope and ambitious plans,and a will to make them happen. In times of regained democracy and freedom, Bělohlávek was getting ready for a new important role as the chief conductor of the Czech Philharmonic.

Main sources

- 1.

VÁŇA, Ladislav (scénář a režie): Tenerezza. Česká televize 1993.

- 2.

ZAPLETAL, Petr: FOK. Padesát let Symfonického orchestru hlavního města Praha. Praha: Supraphon, n. p. 1984, s. 41n.

- 3.

VEBER, Petr; STEHLÍK, Luboš: Jiří Bělohlávek: Fluidum, nebo práce? Harmonie 2018, 31. 5. Available online

- 4.

VÍT, Petr: FOK s novým šéfdirigentem. Hudební rozhledy 1977, č. 12, s. 540.

- 5.

ZAPLETAL, Petr: FOK.Padesát let Symfonického orchestru hlavního města Praha. Praha: Supraphon, n. p. 1984, s. 60.

- 6.

MAREŠ, Vlastimil. Laudatio prof. Vlastimila Mareše. In: Jiří Bělohlávek. Doctor honoris causa. Praha: AMU 2016, s. 7–8.

- 7.

Převzato z Koncertní život. Programový sborník Symfonického orchestru hlavního města Prahy FOK 1981, č. 1, s. 8.

- 8.

ROTHSTEIN, Edward: Concert: Prague Symphony. The New York Times1982, č. XY (12. 11.), s. 21.

- 9.

DOMINGOS, Roy: Prague Orchestra Just Magnificiant. The Macon Telegraph1982, č. XY (25. 10.), s. 3A.

- 10.

ŠVARCOVÁ, Jitka: Poprvé v zemi vycházejícího slunce. Koncertní život 1986, č. 6, s. 2.

- 11.

ŠVARCOVÁ, Jitka: Poprvé v zemi vycházejícího slunce. Koncertní život 1986, č. 6, s. 2.

- 12.

FRÝBOVÁ, Zdena: Pod taktovkou Jiřího Bělohlávka. Naše rodina: zábavný týdeník Československé strany lidové 1982, č. 44, s. 13.

- 13.

SEDLÁČKOVÁ, Pavlína: Dramaturgie vzdělávacích programů v České filharmonii. Magisterská diplomová práce. Ústav hudební vědy FFMU: Brno 2013, s. 51.

- 14.

NEKUDOVÁ, Hana: My dva spolu nedirigujeme. Vlasta 1996, č. 24, s. 11.

- 15.

VEBER, Petr, STEHLÍK, Luboš: Jiří Bělohlávek. Fluidum, nebo práce? Harmonie 2016, č. 2, s. 6–15. Available online

- 16.

Telefonotéka. Český rozhlas Vltava 2016 (14. 1.). Available online

- 17.

UHLÍK, Petr: Hudební mládí. Květy 1988, č. 4, s. 38–39, s. 38.

- 18.

VÍT, Petr: Pražské jaro 80. Hudební rozhledy 1980, č. 7, s. 301.

- 19.

STEHLÍK, Luboš: Rozhovor na přání: Dagmar Pecková. Harmonie 2002, 20. 12. Available online

- 20.

URSÍNOVÁ, Terézia: Impozantní festival. Tvorba 1989, č. 44 (1. 11.), s. 14–15.

- 21.

BOR, Vladimír: Operní večery. Praha: Panton 1981, s. 299.

- 22.

HERRMANNOVÁ, Eva: Staronové Pašije ve Smetanově divadle. Tvorba 1984, č. 10 (7. 3.), s. 10.

- 23.

BERNHEIMER, Martin: Janacek in the Pacific NothWest. Los Angeles Times 1985 (12. 5.) Available online

- 24.

SLAVÍKOVÁ, Jitka: Hry o Marii ve Smetanově síni. Hudební rozhledy1983, č. 3, s. 105.

- 25.

VEJVODOVÁ, Markéta: Rozhovor s Jiřím Bělohlávkem. Český rozhlas 2014, 12. 5. Available online

VÁŇA, Ladislav (scénář a režie): Tenerezza. Česká televize 1993.

ZAPLETAL, Petr: FOK. Padesát let Symfonického orchestru hlavního města Praha. Praha: Supraphon, n. p. 1984, s. 41n.

VEBER, Petr; STEHLÍK, Luboš: Jiří Bělohlávek: Fluidum, nebo práce? Harmonie 2018, 31. 5. Available online

VÍT, Petr: FOK s novým šéfdirigentem. Hudební rozhledy 1977, č. 12, s. 540.

ZAPLETAL, Petr: FOK.Padesát let Symfonického orchestru hlavního města Praha. Praha: Supraphon, n. p. 1984, s. 60.

MAREŠ, Vlastimil. Laudatio prof. Vlastimila Mareše. In: Jiří Bělohlávek. Doctor honoris causa. Praha: AMU 2016, s. 7–8.

Převzato z Koncertní život. Programový sborník Symfonického orchestru hlavního města Prahy FOK 1981, č. 1, s. 8.

ROTHSTEIN, Edward: Concert: Prague Symphony. The New York Times1982, č. XY (12. 11.), s. 21.

DOMINGOS, Roy: Prague Orchestra Just Magnificiant. The Macon Telegraph1982, č. XY (25. 10.), s. 3A.

ŠVARCOVÁ, Jitka: Poprvé v zemi vycházejícího slunce. Koncertní život 1986, č. 6, s. 2.

ŠVARCOVÁ, Jitka: Poprvé v zemi vycházejícího slunce. Koncertní život 1986, č. 6, s. 2.

FRÝBOVÁ, Zdena: Pod taktovkou Jiřího Bělohlávka. Naše rodina: zábavný týdeník Československé strany lidové 1982, č. 44, s. 13.

SEDLÁČKOVÁ, Pavlína: Dramaturgie vzdělávacích programů v České filharmonii. Magisterská diplomová práce. Ústav hudební vědy FFMU: Brno 2013, s. 51.

NEKUDOVÁ, Hana: My dva spolu nedirigujeme. Vlasta 1996, č. 24, s. 11.

VEBER, Petr, STEHLÍK, Luboš: Jiří Bělohlávek. Fluidum, nebo práce? Harmonie 2016, č. 2, s. 6–15. Available online

Telefonotéka. Český rozhlas Vltava 2016 (14. 1.). Available online

UHLÍK, Petr: Hudební mládí. Květy 1988, č. 4, s. 38–39, s. 38.

VÍT, Petr: Pražské jaro 80. Hudební rozhledy 1980, č. 7, s. 301.

STEHLÍK, Luboš: Rozhovor na přání: Dagmar Pecková. Harmonie 2002, 20. 12. Available online

URSÍNOVÁ, Terézia: Impozantní festival. Tvorba 1989, č. 44 (1. 11.), s. 14–15.

BOR, Vladimír: Operní večery. Praha: Panton 1981, s. 299.

HERRMANNOVÁ, Eva: Staronové Pašije ve Smetanově divadle. Tvorba 1984, č. 10 (7. 3.), s. 10.

BERNHEIMER, Martin: Janacek in the Pacific NothWest. Los Angeles Times 1985 (12. 5.) Available online

SLAVÍKOVÁ, Jitka: Hry o Marii ve Smetanově síni. Hudební rozhledy1983, č. 3, s. 105.

VEJVODOVÁ, Markéta: Rozhovor s Jiřím Bělohlávkem. Český rozhlas 2014, 12. 5. Available online