What is characteristic of Dvořák? I believe that the best, the most precise characteristic of Dvořák’s musicality lies in his melodic invention. There is no question about it and it is evident and ever-present from the very start.

The total number of performances of compositions by

Antonín Dvořák: 1 942

The three most performed works

| 256 times | Symphony No. 9 in E minor |

| 154 times | Concerto for cello and orchestra in B minor |

| 139 times | Symphony No. 7 in D minor |

The statistical data compiled, published and shared by Alexander Goldscheider © Citing from his book Jiří Bělohlávek: A Life in Pictures. [ 2 ]

Bělohlávek’s experience with the work of Antonín Dvořák started at an early age as a listener and as a member of the Prague Philharmonic Children’s Choir. As a conductor, he began to study Dvořák’s work already during his studies at the Prague Conservatoire. His Symphony No. 5 was one of the compositions Bělohlávek performed in his graduation concert at the Rudolfinum in 1966.

It was the first of Dvořák’s symphonies I’d had the chance to study and perform. At that time, I was a young man of seventeen or eighteen. It affected me deeply and it was a kind of revelation for me, of course.

Understandably, Dvořák had an important place in the dramaturgy of Czech orchestras in concerts at home and even more so on tours. Moreover, Bělohlávek was often asked to include Dvořák’s work when appearing as a guest conductor with an orchestra abroad. Such a high demand led to the fact that the number of performances of Dvořák’s work by far outnumbered the work of other composers during Bělohlávek’s career.

Despite the high frequency of his “meetings“ with Dvořák, Bělohlávek always avoided falling into routine, which he illustrated also by one anecdote from the time when he was the chief conductor of the Prague Symphony Orchestra: “We went on a tour to the United States and we had twenty-one concerts in twenty-six days and there was always the New World Symphony. I felt uneasy about it of course and I wondered what I could say to the orchestra to motivate them, so that we don’t play it routinely, without any life from the beginning to the end. And so, I came up with something, I asked them to look at it with new eyes each night in the sense that I would make something new, modify something. And that’s what we did, and it was great in the end. We all took delight in it, because we managed to play the symphony differently twenty-one times.“ [ 4 ]

As well as with the work of other composers, Bělohlávek’s style of interpretation of Dvořák developed and deepened over time. Critics and reviewers, who followed the conductor for decades, pointed out this development as well. One such instance was his concert with the Prague Symphony Orchestra in 1997. Dvořák’s Cello Concerto in B minor in an energetic interpretation by Mischa Maisky and Symphony No. 9 were on the programme. The symphony was “in comparison with the performances we used to hear in the eighties, much enriched by new features: nowadays, his New World Symphony is clearer, more chamber-sounding (especially in the woodwinds), finer in its expression, the music’s flow is smooth and matter-of-course. As if the orchestra observed with curiosity how their former chief conductor matured to deliver a concentrated interpretation of a work he’d known intimately…” [ 5 ]

Dvořák’s works were not heard only at joyful and festive events, but also at moments of national mourning, as in December 2011 when the Czech Republic was bidding farewell to Václav Havel. On Wednesday, 21 December, the Czech Philharmonic under Bělohlávek’s baton played at the funeral ceremony in the Vladislav Hall of Prague Castle, and on Friday, 23 December, at the requiem mass in St.Vitus Cathedral. There they played Dvořák’s Requiem, parts of Händel’s oratorio Messiah, Dvořák’s Biblical song By the Rivers of Babylon and Saint Wenceslas Chorale.

The Czech Philharmonic and Jiří Bělohlávek playing at the funeral ceremony in the Vladislav Hall | Photo ČTK (Available online)

The worldwide popularity of Antonín Dvořák’s music was also strongly mirrored in Bělohlávek’s discography. With leading orchestras and soloists, he made many recordings of major orchestral and chamber works for Czech labels and even more for labels abroad.

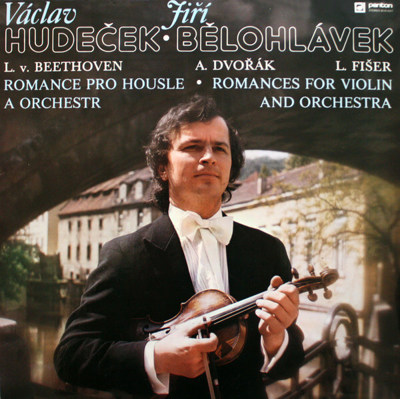

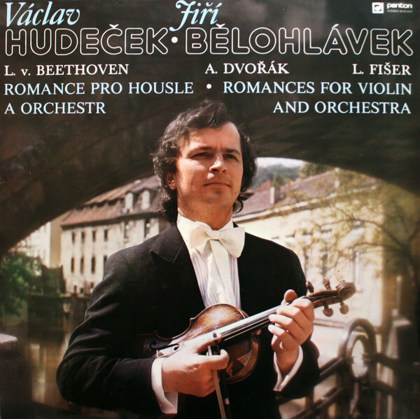

Bělohlávek began a series of Dvořák recordings in the 1980s, as the chief conductor of the Prague Symphony Orchestra and the permanent conductor of the Czech Philharmonic. With the latter orchestra and the pianist Ivan Moravec, they recorded Dvořák’s Piano Concerto in G minor in June 1982. The recording was released on a Suprahnon LP a year later. Also in 1982, he recorded Dvořák with the Prague Symphony Orchestra and Václav Hudeček. On a Panton album entitled Romance pro housle (Romance for violin), there appeared Dvořák’s Romance for Violin and Orchestra in F minor, and works by Beethoven and Luboš Fišer.

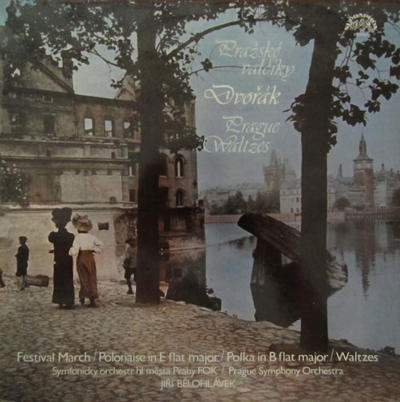

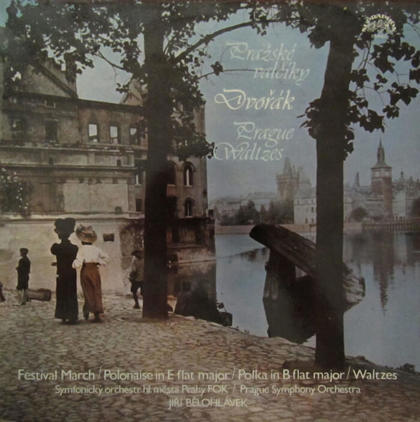

With the Prague Symphony Orchestra and the soloist Michaela Fukačová, Bělohlávek recorded Dvořák’s Cello Concerto in B minor for Panton in 1987. An LP of the Supraphon label entitled Prague Waltzes, recorded with the same orchestra, was released in 1988 and contained Dvořák’s lesser-known works such as the Prague Waltzes, Polonaise in E flat major and Polka in B flat major. The year 1988 brought another LP with Václav Hudeček and the Czech Philharmonic, which included the Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 53, Romance for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 11 and Mazurek for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 49.

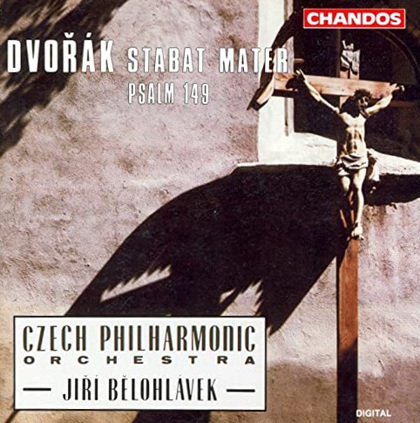

The early nineties were marked by many recordings with the Czech Philharmonic. First, they recorded Symphony No. 9and Carnival for the Supraphon label in 1990, and then they made many recordings for the English label Chandos. Beginning in 1990, the following works by Dvořák were recorded in the Spanish Hall of Prague Castle and gradually released - Stabat Mater and Psalm 149 in collaboration with the Prague Philharmonic Choir and Bambini di Praga (recorded 1990, released 1991), Symphony No. 5 (recorded 1995, released 1996), Symphony No. 6 (recorded 1992, released 1993), Symphony No. 7 (recorded 1992, released 1995) and Symphony No. 8 (recorded 1991, released 1992). The symphonic albums also contained the Symphonic Poems after Karel Jaromír Erben: The Water Goblin, op. 107, The Noon Witch, op. 108, The Golden Spinning Wheel, op. 109, The Wild Dove, op. 110, and Scherzo capriccioso, op. 66 and Nocturne in B major, op. 40.

Bělohlávek’s recording of the New World Symphony, which is now over ten years old, is the paragon of precision and moderation (and, by the sound modesty, it is almost foreshadowing his later recordings with the PKF - Prague Philharmonia). The strict baton here creates out of the New World Symphony a dramatic and tight-knit work, where moments of battle alternate with wistful moments.

The Chandos recording fixes the mature, time-proved interpretation, in which, typically for Bělohlávek since his young age, nothing is left to chance. In comparison with other recordings known to us, the recording is interesting thanks to its great emphasis on colourfulness of Dvořák’s score and somewhat slower tempos. This approach avoids the slightest risk of seemingly ingenuine bathos (the introduction to the finale) and enables well-arched phrasing (…) Bělohlávek’s choice of unhurried tempos enabled him, moreover, to bring the beautiful lyricism of Dvořák’s themes to the forefront. The Czech Philharmonic is playing in a concentrated way, and freely and joyfully at the same time showing delight in the music. In this way, the almost wastefully large number of moods present in the Eighth Symphony is employed to the full.

...Jiří Bĕlohlávek draws arguably the most articulate and sumptuous response of all from the Czech PO, and his patient, warmly affectionate and generously flexible approach is consistently endearing. Silky poise and songful ardour combine to especially potent effect in the slow movement, at the end of which (after marginally too long a pause) Bĕlohlávek effects an eloquently shaped transition into the Scherzo.

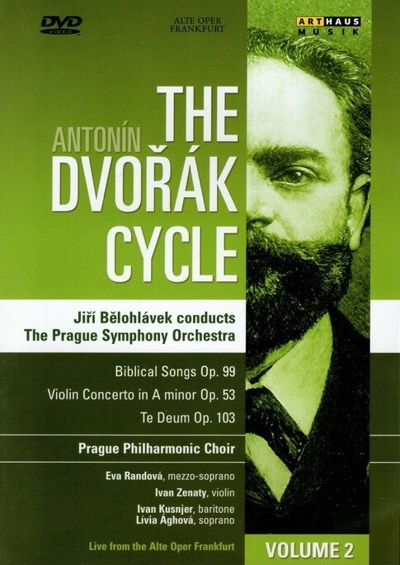

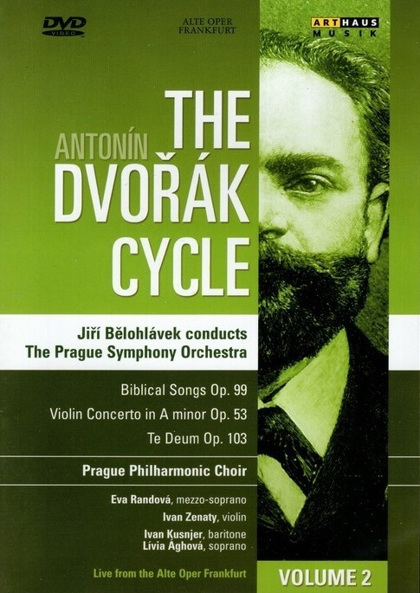

In the 1990s, Bělohlávek made important Dvořák recordings also with the Prague Symphony Orchestra FOK. Together they took part in The Dvořák Cycle project of the German label Arthaus Music which in 1993 released six DVDs of live concerts of the orchestra from the Alte Oper in Frankfurt. Bělohlávek conducted the orchestra on the first two DVDs, the first featuring Symphony No.7, the Slavonic Dances and Romance for Violin and Orchestra with Ivan Ženatý. The second DVD presented Dvořák’s Biblical Songs with the soloist Eva Randová, his Violin Concerto again with Ivan Ženatý and Te Deum with Ivan Kusnjer and Lívia Ághová. On the other four CDs, the orchestra was conducted by Petr Altrichter and Libor Pešek.

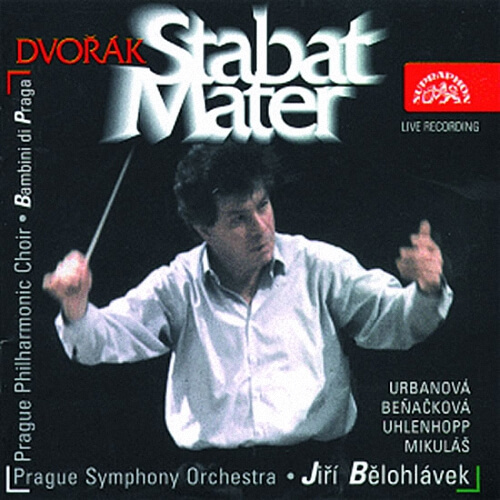

Bělohlávek was also involved in a major Supraphon project with the Prague Symphony Orchestra, which was to record the complete Dvořák by 2004, they were to perform all the vocal-symphonic works. In November 1995, a live recording of a concert of The Spectre’s Bride was made (released in 1996), featuring the Prague Philharmonic Choir led by Pavel Kühn, and the soloists Eva Urbanová, Ľudovít Ludha and Ivan Kusnjer. In the spring of 1997, a live recording of Stabat Mater followed, with the vocalists Eva Urbanová, Marta Beňačková, John Uhlenhopp, Peter Mikuláš, Prague Philharmonic Choir and Bambini di Praga.

Dvořák’s work was also an important part of the recording programme of the PKF – Prague Philharmonia. Bělohlávek sought to achieve a representative presence of the orchestra on the recording market and the name of Jiří Bělohlávek and the PKF – Prague Philharmonia appeared on seven Dvořák albums. The first was a CD of Dvořák’s violin works with František Novotný in 1996 (Matouš label). In the same year they recorded Dvořák’s Legends and the Czech Suite for the Clarton label.

The recording received minute care – both in the sense of its musicality and expression. Every voice, every bow, every movement in tempo or dynamics fits into the precise plan of the development of the individual compositions. And at the same time, the compositions sound simple – as they were meant to sound by their author, with emphasis on the melodic richness of the archaic Slavonic character. (…) Jiří Bělohlávek individualized each work with precision, emphasising its unique invention, mood and instrumentation. (…) when you listen attentively to the fifteen movements of the two works by Dvořák presented on this CD, you will hear that the PKF – Prague Philharmonia have already gained their own original sound and Bělohlávek can use it with confidence as an instrument. This CD is a paramount achievement.

Dvořák’s Serenade appeared on the album entitled “Dvořák – Suk: Serenades”, released by Supraphon in 1996. Two years later, Multisonic released Dvořák’s Slavonic Dances (1998).

Bělohlávek’s complete set of the Slavonic Dances reflects the conductor’s nature perfectly: the otherwise usual spontaneity in the choice of tempi which tends to result in hollow effects when performed by other ensembles of lower quality is here replaced by careful control, that – to be fair - can seem somewhat more academic when compared with Šejna’s recording or Smetáček’s performances of the dances. This, however, enables each number to have much more sensitive articulation of phrasing and a clearer space for the manifestation of Dvořák’s ingenious processes of instrumentation. (…) Bělohlávek’s recording represents, moreover, another legitimate proof that the conductor’s goal-directed work with young musicians leads to indisputable interpretative qualities of the ensemble.

Dvořák’s anniversary in 2004 brought a number of recordings and Bělohlávek and the PKF – Prague Philharmonia also contributed their share. In March 2003, they made a studio recording of Dvořák’s opera The Stubborn Lovers, which was composed in 1874 as Dvořák’s third opera (it had to wait for its premiere until 1881). The baritone Roman Janál, tenor Jaroslav Březina, alto Jana Sýkorová, soprano Zdena Kloubová, bass Jaroslav Brych and the Prague Philharmonic Choir sang on the recording. The CD was released in 2004.

In September 2003, Bělohlávek with the orchestra and the German violinist Isabella Faust recorded the Concerto for Violin and Orchestra in E minor, Op. 53. The recording was also released in 2004 by Harmonia Mundi.

One recognizes, right from the second note of the recording of Dvořák’s Violin concerto, that one is listening to something exceptional. It is exactly the orchestra’s second note, the low a, which is often unclear, unsynchronized, muffled by the surrounding sound. However, when performed by the PKF – Prague Philharmonia, it sounds precise, energetic and legible. As if the orchestra wanted to give us hints from the very start about the way it is going to play right until the end of the piece: to care for every detail, to be wholly transparent, to lead the listener’s ear deeper into Dvořák’s score than usual. (…) The recording shows an exceptionally successful connection between the soloist, orchestra and the conductor, all on the same wavelength, knowing that not even concertos are about superficial effects. This knowledge really pays off and I dare say their performance is the best of all the recording activities done in celebration of Dvořák’s anniversary.

In 2004 the Harmonia Mundi label made a recording of the famous Concerto in B minor for Cello and Orchestra, Op. 104with the then young French cellist Jean-Guihen Queyras.

Jiří Bělohlávek has chosen the approach in which the orchestra remains in the role of an accompanist and lets the solo voice stand out. The orchestra’s part has a much more chamber-like sound – the orchestra being faithful to its name, which from Czech would be translated as the Prague Chamber Philharmonia – and at the same time keeps its colourfulness, although of a scale closer to concertos of the classical period. The climaxes are dramatic, but still within a very modest style. This can also be the result of the recording technology which placed the soloist in the forefront – which is not meant as criticism as the cellist Jean-Guihen Queyras has always enough to offer.

At the same time, Bělohlávek recorded the Cello Concerto also with the Czech Philharmonic and the cellist Jiří Bárta. The recording was made in May 2004 in the Dvořák Hall at the Rudolfinum and was released later that year on an attractive double-CD entitled Antonín Dvořák Piano & Cello Concertos. The piano concerto was performed by the pianist Martin Kasík and conductor Jiří Kout.

The Cello Concerto is one of Dvořák’s most performed works and one may think there could be nothing new that one could bring. Jiří Bárta and Jiří Bělohlávek, however, achieved the almost impossible. From the very first tones of this impressive recording, we are ushered into a magical landscape, which we have known intimately and at the same time see it as something new, in an unexpectedly beautiful light with countless surprising details. The performers keep our attention throughout, with electrifying suspense and let us breathe out only with the last tones of the final catharsis. Jiří Bárta’s performance, however mature and detached, is so expressive that at many moments one can hardly imagine a more intense artistic confession. The orchestra under the baton of Jiří Bělohlávek is bursting with beautiful colours, from bright and clear to velvety soft and dark. The soloists of the orchestra deserve special praise, especially the winds. Each solo from the orchestra is so original that the names of the performers would deserve to be written right next to those of the soloist and the conductor.

Another important recording of the Czech Philharmonic was made in 2004. It was a live recording of Dvořák’s oratorio Saint Ludmila which Bělohlávek performed at two Prague Spring concerts on 15 and 16 May. It was the first recording of the work after long forty years, when a recording with Beno Blachut was made. The concerts, and the recording, featured leading vocal soloists - Eva Urbanová, Bernarda Fink, Stanislav Matis, Aleš Briscein and Peter Mikuláš - alongside the conductor, the orchestra and two choirs (Prague Philharmonic Choir and Bambini di Praga).

Bělohlávek devoted a lot of time and energy to prepare this performance as one can notice both in details and the overall outline of the composition. The monumental work seems to have been carved from one enormous block, offering at the same time many beautiful details in the choral passages, which comprise the leading component of the work, as well as in the solo parts.

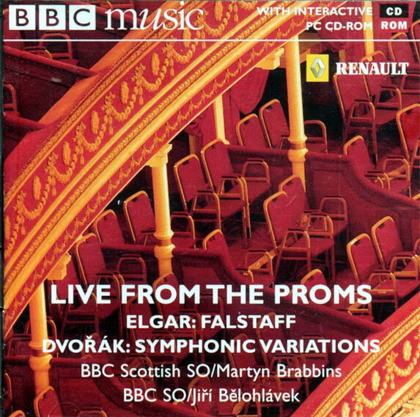

While Bělohlávek was the chief conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra, Dvořák and other Czech composers, were included in their concerts frequently, be it subscription concerts, tours, and special events such as the BBC Proms. At this festival, one could hear Dvořák’s Symphonic Variations performed by Bělohlávek and the orchestra in August 2000. A live recording was released on a CD in 2001 entitled Live from The Proms (label BBC Music Magazine). Dvořák was heard again at the Royal Albert Hall in 2008 (Slavonic Dances) and in 2012 (Symphony No. 7).

“Is being a Slav still something living?” – “For me it is. I feel the identity very strongly in the dances and I believe I pass that on to the musicians and subsequently onto the listeners very spontaneously, because this music really springs from the Slavonic element, and the instrumentation and composition is masterful. Moods change and the whole of eight dances seems like a colourful bouquet. But to avoid misunderstanding – it is always a tough nut to crack. The Slavonic Dances belong to one of the most difficult of Dvořák’s scores as they require a learned art of interpretative distinction. At that time, Dvořák used to write the dynamics globally. If it is marked fortissimo, each player has fortissimo. If you play it like this, the dances are just loud and fast, of course. The score, however, hides much poetry, which requires a greatly detailed work. And that’s what interests me the most, because then the score blossoms – if you uncover and refine the basis, beautiful blooms appear.”

The first CD he released with the orchestra as its chief conductor was a double CD presenting Dvořák’s works. The Warner Classics album includes his Symphony No. 5 in F major, Op. 76 and Symphony No. 6 in D major, Op. 60, Scherzo capriccioso, Op. 66 and A Hero’s Song, Op. 111. Symphony No. 6 was recorded live in 1999 at a concert at the Royal Festival Hall, the other works were recorded in a studio in March 2006.

Bělohlávek’s London recordings are a proof of how effectively a conductor can lead an orchestra to feel in style. Right from the very first bars of any of the four compositions presented (…), the conductor’s intention to emphasise the melody and cantilena – both very prominent in Dvořák’s works - is apparent. It is very convincing especially when it is rendered in a natural way, without great speculation, which on some other recordings can lead to pompous interpretation. One of Bělohlávek’s most prominent attributes is lyricism – in the overall sound, including the swifter movements. The conductor is very sparse as far as full sound is concerned, which makes it possible for the climactic passages to sound impressive. (…) Jiří Bělohlávek has a very supportive background in the orchestra. In addition to the typically English homogeneous sound image (fabulous brass as well as other sections!), the BBC Symphony Orchestra – used to completing tasks on a larger dramaturgical scale than some of the other London orchestras – is very flexible and his Dvořák is truly full of style.

Bělohlávek serves “the composition”, not showing off his “interpretation”. His Dvořák’s Fifth Symphony recorded with the BBC Symphony Orchestra sets a benchmark for my assessment of all further recordings in the future.

In 2012, he recorded Schumann’s and Dvořák’s Piano Concertos with the BBC Symphony Orchestra and the Swiss pianist Francesco Piemontesi. While the Schumann concerto was recorded live, the Dvořák concerto was a studio recording. The soloist and the conductor chose to work with Dvořák’s original version of the concerto without the changes made in the 1910s by the famous piano professor Vilém Kurz. Both recordings were released on the Naïve label in 2013.

While one can argue whether we need any more recordings of the Schumann (well over 100 available at the last count), there are only about 13 of the Dvořák, not all of them in such feisty, committed performances as this new one and certainly not in such good sound, notwithstanding František Maxián and Václav Talich in 1951 using the Kurz revision. Here I think Jiří Bělohlávek and the BBC SO have the edge on their Pentatone rivals. Listening to Piemontesi and returning again to the great Ivan Moravec’s account (Kurz’s version under Bělohlávek again) makes you wonder if it isn’t time the Dvořák gained a place in the regular concerto repertoire.

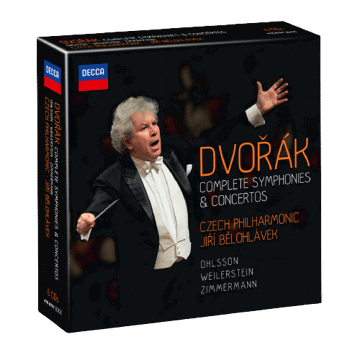

Bělohlávek’s recording of all nine of Dvořák’s symphonies and three concertos was undoubtedly the highlights of Bělohlávek’s activities involving the work of Dvořák. They were recorded with the Czech Philharmonic in October 2012 after Bělohlávek was appointed the chief conductor for the second time. When planning the project, the orchestra’s management addressed renowned international labels and already the second one, the British label Decca, said yes and very enthusiastically, too.

I see it as one of the greatest challenges of the first seasons. I have never conducted the First, Second and Third Symphony before. And it is a known fact that they are problematic. I have been lying in the scores for six months now so that I can do it well. Dvořák’s early symphonies are very long and are not yet masterpieces of the highest kind – we must perform them in such a way that is true to the original and at the same time makes most of them and makes them accessible and vivid for today’s audience. That is no simple task.

The recordings of all the symphonies and of the Violin Concerto with Frank Peter Zimmermann were made live at subscription concerts in the 2012/2013 and 2013/2014 seasons. The Piano Concerto in G minor with Garrick Ohlsson and the Cello Concerto with Alisa Weilerstein were recorded in the studio.

The Czech Television was also involved in the project and the team of the director Adam Rezek filmed all the concerts. A nine-episode TV programme was made using the recorded musical material and talks in which Bělohlávek and Marek Eben discuss Dvořák’s symphonies.

Parallel to these activities, a time-lapse documentary was filmed by the director Barbara Willis Sweete. The film covers chronologically the process of recording the symphonies and concertos, both in concerts and studios. Against the backdrop of Dvořák’s life and work, it captures the atmosphere accompanying the changes in the Czech Philharmonic through the eyes of the players, conductor and management.

Bělohlávek – true to his nature – got involved in the project with all his verve and contributed his views about the sound and TV direction, too, in order to achieve the highest possible quality and to avoid unwanted extremes in the form of a sequence of fast clips or, on the other hand, static unmoving camera that had been typical in the 1970s.

…I have a very precise idea of the sound image I would like to achieve. And it is true that not always the result you see in the studio is the same one as you had experienced a minute before on the stage. That is a fundamental thing and I always try to persuade my colleagues – sound engineers and the director – to come and listen to the music in the hall and to try to record it as they had heard it and to create a recording faithful to the sound in the hall. In our case, we have an excellent and well collaborating team, and the technology is also perfect. Practically, we have the possibility to adjust the sound ratios after the recording. But of course, the basic and decisive part must be created in the hall by us musicians and we have to hand it in in a somewhat finished form.

Still before the release of the complete Dvořák set, the Decca label published the Cello Concerto together with some shorter compositions, such as Rondo for Cello and Piano in G minor, the fourth part of the Gypsy Songs or the eight Slavonic dance.

How disarmingly unforced and personable the Czech Philharmonic sound in the Concerto’s introduction, Jiří Bĕlohlávek providing a quietly authoritative, glowingly affectionate launching pad for Alisa Weilerstein’s superbly articulate entry.

Finally in August 2014, the Dvořák Complete Symphonies & Concertos featuring all of Dvořák’s symphonies and all three concertos is released.

…the whole set is beautiful performance after beautiful performance. The live acoustics cast an absolutely lovely sheen around the winds, but the whole orchestra distinguishes itself and proudly upholds a world-famous performance tradition in this music.

Looking back on the last eighteen months and trying to sum up my feelings from the whole project of recording of Dvořák’s symphonies and concertos, I am happy to say that it was a beautiful time when we lived with his music. We enjoyed it enormously, we learned a great deal and strengthened our love for our Master.

The Dvořák Concerto with the Czech Philharmonic was an extraordinary experience for me. I was surprised by the sound culture and the overall refinement of the orchestra. I thoroughly enjoyed performing with the Czech Philharmonic and Jiří Bělohlávek in concerts and I am very glad that we had the opportunity to record this concerto for the complete Dvořák set.

The EUROARTS company released also audio-visual versions of the symphonies in 2016. Five DVDs contain over eight hours of first-class music and journalism. The symphonies are complemented by the eighty-minute long documentary Objevování Dvořáka (Discovering Dvořák), directed by Barbara Willis Sweete.

Bělohlávek’s predominantly fast tempos in the first two symphonies allow vast panoramas to emerge with no danger of their collapsing under their own weight; the performance of the Second is particularly fine and allows its radiance and imagination to emerge unhindered. The same approach works less well in the Third, whose magnificent first movement feels a little constricted. Bělohlávek makes the best of the Fourth Symphony’s virtues, emphasising lyrical aspects and bringing a convincing swagger to the scherzo. The performances of the more Classically-orientated middle symphonies are all splendid; in each, compelling attention to detail never threatens symphonic integrity. The flexibility Bělohlávek adopts in the first movement of the Eighth and wholehearted embrace of the wide-ranging narratives of the slow movement and finale produce a rendition of breathtaking conviction. The performance of the New World is unfailingly expert and beautifully played if lacking the last ounce of excitement. Overall these readings rank with some of the finest, and throughout radiate a profound authenticity.

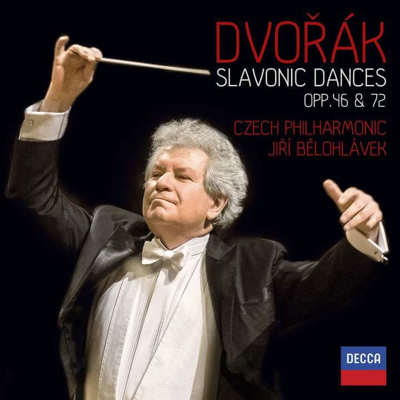

Following the release of the Dvořák set, Bělohlávek continued to record his works with the Czech Philharmonic. According to the long-term plan of collaboration with the Decca label, they recorded the Slavonic Dances in 2014 and 2015 (released in October 2016). In 2016, they recorded Stabat Mater at a subscription concert (released in May 2017) with soloists Eri Nakamura, Elisabeth Kulman, Michael Spyres, Jongmin Park and the Prague Philharmonic Choir. The last album, released in March 2020, included three of Dvořák’s works - Requiem, Biblical Songs performed by Jan Martiník and Te Deum. The Biblical Songs are the last studio recording Bělohlávek made. Requiem and Te Deum were recorded after Bělohlávek’s decease under the baton of his student Jakub Hrůša.

There is nothing lacking in his interpretation of Dvořák’s Stabat Mater, the composition seems to have been written for him. Not as a eulogy though, it is composed in a manner that Bělohlávek can interpret it on the top level and truthfully. He lets the middle voices speak with expression, he sings the melodic arches without lagging, dynamic climaxes grow as if forced by pressure from within, and, despite its monumentality, the structure of the music never stops to be legible. The Czech Philharmonic plays under Bělohlávek’s direction as a perfectly balanced mechanism assembled from top-class components. The Prague Philharmonic Choir with Lukáš Vasilek as the chorus-master is well articulated and does not let a single word slip.

...the new recording of the Slavonic Dances can be without doubt placed in the group of the orchestra’s recordings where each recording is specific and extraordinary. Its most valuable and impressive feature is the conception of tempi and expressive means. The detailed nuances (...) are very far from the usual tradition and are the result of thorough conceptual preparation as well as of soulful understanding of particular musical passages and the endeavour to interpret them without any burden of tradition.

Dvořák was on the programme of Bělohlávek’s last recorded concert ever which took place on 28 April 2017 in Munich. The Bavarian Radio Symphonic Orchestra played three of “Bělohlávek’s” composers - Martinů, Janáček and Dvořák. Dvořák was represented by the Biblical Songs performed by Magdalena Kožená. Thanks to the Euroradio exchange programme, the recorded concert is available on the Czech Radio Vltava website.

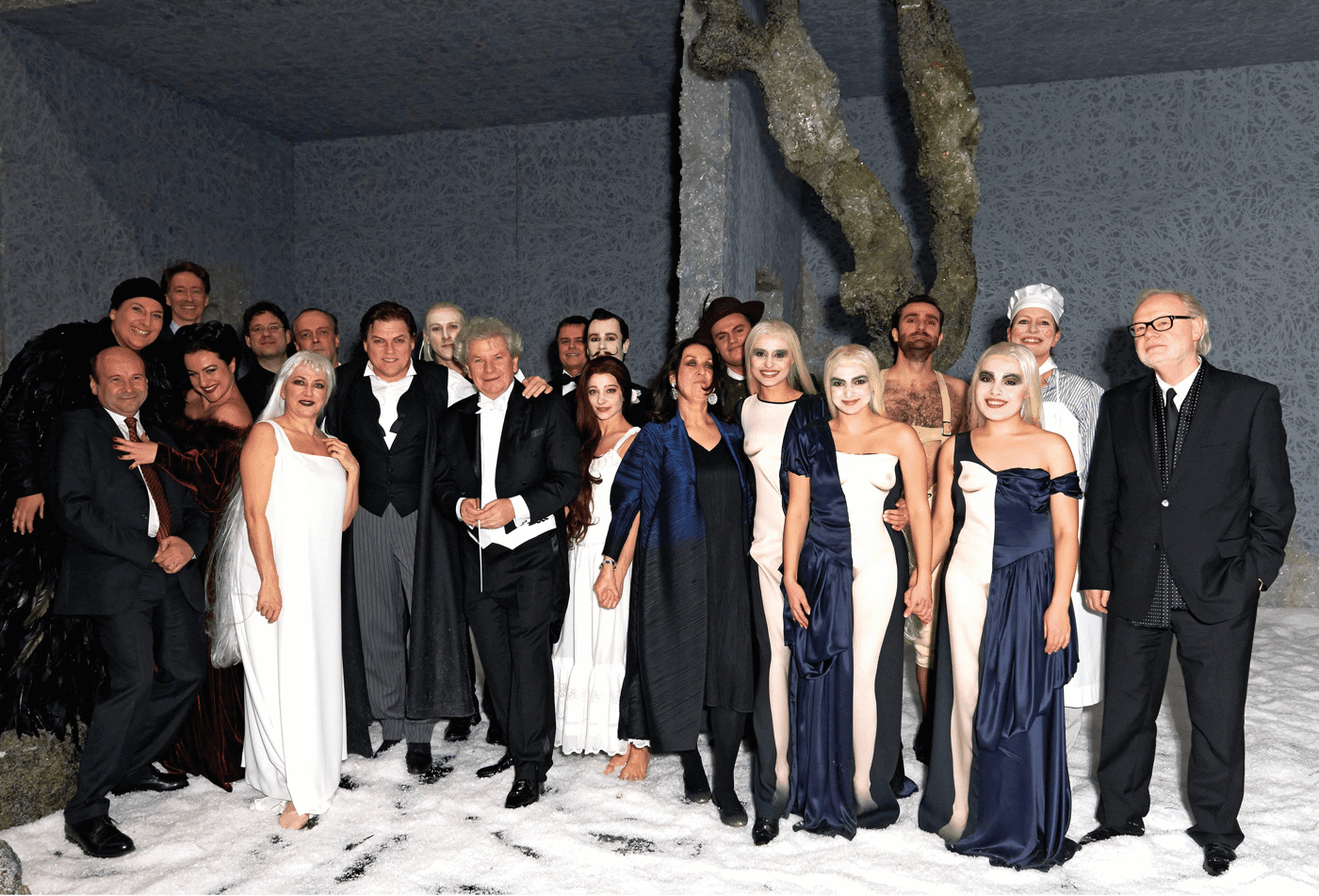

Bělohlávek’s repertoire and discography of Dvořák’s works would not be complete without opera. Although he staged only one of Dvořák’s operas – Rusalka, he made four productions of it. The first was in 1998 on the scene of the National Theatre in Prague under the stage direction of Alena Vaňáková.

In 2005, Bělohlávek staged Rusalka at the Opéra Bastille in Paris with Olga Guryakova in the title role and Stuart Skelton as the Prince. Four years later, in March 2009 it was the performance at the Metropolitan Opera in New York with Renée Fleming as Rusalka and the Latvian tenor Aleksandrs Antoņenko as the Prince. And then in the summer, Bělohlávek revisited the Glyndebourne Festival and staged Rusalka there. Rusalka was sung by Ana María Martínez, the Prince by Brandon Jovanovich and Ježibaba by Larissa Diadkova. A live recording was released on CD in 2009.

Rusalka is a deeply felt work and its power is in its truthfulness. It does not pretend anything, it does not stylize itself in any way, it is music of the heart. It touches on all aspects of human nature - love, desire, passion, betrayal, revenge, death, forgiveness and sacrifice - in an arch so stunning and natural that it takes one’s breath away...

In 2012 in London, Bělohlávek and the BBC Symphony Orchestra gave a concert performance of The Jacobin. The singing cast was almost only Czech and Slovak. Bělohlávek’s last Rusalka was at the State Opera in Vienna. It was a debut for Bělohlávek at this famous opera house. The production featured, among others, the Bulgarian soprano Krassimira Stoyanova as Rusalka, Michael Schade as the Prince, Günther Groissböck as Vodník and Janina Baechle as Ježibaba.

The musical staging by Jiří Bělohlávek was a huge success, and rightly so. Dvořák’s score is a gem of instrumentation, and here it shone in all colours. The audience greeted the conductor after each interval by clapping and cheering, and at the end he received an ovation comparable to that of the principal singer.

In connection with the work and person of Antonín Dvořák, Bělohlávek was not only active as a conductor and music director, but also as an organiser. After the passing of Charles Mackerras, an expert in Czech music, Bělohlávek became president of The Dvořák Society in Great Britain. Founded in 1974, the Society has over seven hundred members from English-speaking countries from different continents. Its aim is to promote not only Antonín Dvořák, but also the music of other Czech and Slovak composers, as well as Czech and Slovak performers. After Bělohlávek’s death, Jakub Hrůša took over as president.

At the general meeting of 2013, Bělohlávek was elected honorary president of the Czech Antonín Dvořák Society. In 2014, he received the Antonín Dvořák Prize, awarded by the Academy of Classical Music, the organizer of the Dvořák Prague Festival, for promoting the composer’s work. The award was decided unanimously by the Council of Academics. The conductor received the award on the occasion of a concert with the Czech Philharmonic on 16 November 2014 at the Carnegie Hall in New York, where Dvořák’s Symphony “From the New World” had had its world premiere.

Main sources

- 1.

KADLEC, Petr; BAŤA, Blahoslav: Jiří Bělohlávek: Dvořák jako by na vás občas mrknul okem. Aktualne.cz 2014, 21. 8. Available online

- 2.

GOLDSCHEIDER, Alexander: Jiří Bělohlávek: A Life in Pictures. 2017. Available online

- 3.

KADLEC, Petr; BAŤA, Blahoslav: Jiří Bělohlávek: Dvořák jako by na vás občas mrknul okem. Aktualne.cz 2014, 21. 8. Available online

- 4.

KADLEC, Petr; BAŤA, Blahoslav: Jiří Bělohlávek: Dvořák jako by na vás občas mrknul okem. Aktualne.cz 2014, 21. 8. Available online

- 5.

ZAPLETAL, Petar: Mischa Maisky, Jiří Bělohlávek a FOK. Hudební rozhledy 1997, číslo 11, s. 18.

- 6.

BÁLEK, Jindřich: Antonín Dvořák: Symfonie č. 9 e moll „Z nového světa“, Karneval, Symfonické variace. Harmonie 2003, č. 2, s. 40.

- 7.

ZAPLETAL, Petar: Dvořákova Anglická s Bělohlávkem. Gramorevue 1993, č. 9, s. 12

- 8.

ACHENBACH, Andrew: Dvořák’s Fifth Symphony – which recording is best? Gramophone 2016, 8. 3. Available online

- 9.

SMOLKA, Jaroslav: Antonín Dvořák: Legendy, op. 59, Česká suita, op. 39, Pražská komorní filharmonie, řídí Jiří Bělohlávek (Clarton). Hudební rozhledy 1997, č. 3, s. 45.

- 10.

ZAPLETAL, Petar: MULTISONIC 31 0452 – 2. Antonín Dvořák. Slovanské tance op. 46 a op. 72, Pražská komorní filharmonie, dirigent Jiří Bělohlávek. Hudební rozhledy 1999, číslo 10, s. 44–45.

- 11.

SRNKA, Miroslav: Antonín Dvořák. Koncert pro housle a orchestr a moll op. 53, Trio pro klavír, housle a violoncello f moll op. 65. Harmonie 2004, č. 5, s. 38.

- 12.

BÁLEK, Jindřich: Antonín Dvořák: Koncert h moll pro violoncello a orchestr op. 104, Dumky op. 90. Harmonie 2005, č. 11, s. 46.

- 13.

NĚMEC, Věroslav: Antonín Dvořák. Koncert h moll pro violoncello a orchestr op 104, Koncert g moll pro klavír a orchestr op. 33. Harmonie 2005, č. 4, s. 43.

- 14.

STEHLÍK, Luboš: Antonín Dvořák: Svatá Ludmila op 71. Harmonie 2005, č. 12, s. 45.

- 15.

VEBER, Petr: Jiří Bělohlávek uvádí v Londýně hodně české hudby. Český rozhlas D-dur 2008, 3. 9. Available online

- 16.

STEHLÍK, Luboš; HURNÍK, Lukáš; VÍTEK, Bohuslav: Antonín Dvořák – Symfonie č. 5 F dur op. 76 a č. 6 D dur op. 60, Scherzo capriccioso op. 66, Píseň bohatýrská op. 111. Casopisharmonie.cz 2007, 10. 8. Dostupné online

- 17.

STEHLÍK, Luboš; HURNÍK, Lukáš; VÍTEK, Bohuslav: Antonín Dvořák – Symfonie č. 5 F dur op. 76 a č. 6 D dur op. 60, Scherzo capriccioso op. 66, Píseň bohatýrská op. 111. Casopisharmonie.cz 2007, 10. 8. Available online

- 18.

NICHOLAS, Jeremy: Schumann; Dvořák: Piano Concertos. Gramophone 2013, 3. 8. Available online

- 19.

VEBER, Petr; STEHLÍK, Luboš: Jiří Bělohlávek – perfekcionista, pro něhož není dokonalost cílem, ale začátkem. Harmonie 2012, 9. 10. Available online

- 20.

Akademie. Nad novou kompletní nahrávkou Dvořákových symfonií. O vzniku skladeb i jejich natáčení Českou filharmonií a Jiřím Bělohlávkem. Český rozhlas 2014, 10. 9. Available online

- 21.

ACHENBACH, Andrew: Dvořák Cello Concerto. Gramophone 2014, 22. 4. Available online

- 22.

WIGMAN, Brian: Antonín Dvořák. Complete Symphonies & Concertos. Classical.net 2014. Available online

- 23.

SMACZNY, Jan: Dvořák’s Symphonies Nos 1-9 performed by the Czech Philharmonic, conducted by Jiří Bělohlávek. ClassicalMusic 2017, 14. 3. Available online

- 24.

KLEPAL, Boris: Bělohlávkova nahrávka s Českou filharmonií: Stabat Mater interpretoval, jako by ji Dvořák napsal pro něj. iHned 2017, 28. 6. Available online

- 25.

VÍTEK, Bohuslav: Antonín Dvořák Slovanské tance. Harmonie 2017, č. 2, s. 63.

- 26.

REITTEREROVÁ, Vlasta: Nová vídeňská Rusalka – promyšlená linie. Opera Plus 2014, 11. 2. Available online

KADLEC, Petr; BAŤA, Blahoslav: Jiří Bělohlávek: Dvořák jako by na vás občas mrknul okem. Aktualne.cz 2014, 21. 8. Available online

GOLDSCHEIDER, Alexander: Jiří Bělohlávek: A Life in Pictures. 2017. Available online

KADLEC, Petr; BAŤA, Blahoslav: Jiří Bělohlávek: Dvořák jako by na vás občas mrknul okem. Aktualne.cz 2014, 21. 8. Available online

KADLEC, Petr; BAŤA, Blahoslav: Jiří Bělohlávek: Dvořák jako by na vás občas mrknul okem. Aktualne.cz 2014, 21. 8. Available online

ZAPLETAL, Petar: Mischa Maisky, Jiří Bělohlávek a FOK. Hudební rozhledy 1997, číslo 11, s. 18.

BÁLEK, Jindřich: Antonín Dvořák: Symfonie č. 9 e moll „Z nového světa“, Karneval, Symfonické variace. Harmonie 2003, č. 2, s. 40.

ZAPLETAL, Petar: Dvořákova Anglická s Bělohlávkem. Gramorevue 1993, č. 9, s. 12

ACHENBACH, Andrew: Dvořák’s Fifth Symphony – which recording is best? Gramophone 2016, 8. 3. Available online

SMOLKA, Jaroslav: Antonín Dvořák: Legendy, op. 59, Česká suita, op. 39, Pražská komorní filharmonie, řídí Jiří Bělohlávek (Clarton). Hudební rozhledy 1997, č. 3, s. 45.

ZAPLETAL, Petar: MULTISONIC 31 0452 – 2. Antonín Dvořák. Slovanské tance op. 46 a op. 72, Pražská komorní filharmonie, dirigent Jiří Bělohlávek. Hudební rozhledy 1999, číslo 10, s. 44–45.

SRNKA, Miroslav: Antonín Dvořák. Koncert pro housle a orchestr a moll op. 53, Trio pro klavír, housle a violoncello f moll op. 65. Harmonie 2004, č. 5, s. 38.

BÁLEK, Jindřich: Antonín Dvořák: Koncert h moll pro violoncello a orchestr op. 104, Dumky op. 90. Harmonie 2005, č. 11, s. 46.

NĚMEC, Věroslav: Antonín Dvořák. Koncert h moll pro violoncello a orchestr op 104, Koncert g moll pro klavír a orchestr op. 33. Harmonie 2005, č. 4, s. 43.

STEHLÍK, Luboš: Antonín Dvořák: Svatá Ludmila op 71. Harmonie 2005, č. 12, s. 45.

VEBER, Petr: Jiří Bělohlávek uvádí v Londýně hodně české hudby. Český rozhlas D-dur 2008, 3. 9. Available online

STEHLÍK, Luboš; HURNÍK, Lukáš; VÍTEK, Bohuslav: Antonín Dvořák – Symfonie č. 5 F dur op. 76 a č. 6 D dur op. 60, Scherzo capriccioso op. 66, Píseň bohatýrská op. 111. Casopisharmonie.cz 2007, 10. 8. Dostupné online

STEHLÍK, Luboš; HURNÍK, Lukáš; VÍTEK, Bohuslav: Antonín Dvořák – Symfonie č. 5 F dur op. 76 a č. 6 D dur op. 60, Scherzo capriccioso op. 66, Píseň bohatýrská op. 111. Casopisharmonie.cz 2007, 10. 8. Available online

NICHOLAS, Jeremy: Schumann; Dvořák: Piano Concertos. Gramophone 2013, 3. 8. Available online

VEBER, Petr; STEHLÍK, Luboš: Jiří Bělohlávek – perfekcionista, pro něhož není dokonalost cílem, ale začátkem. Harmonie 2012, 9. 10. Available online

Akademie. Nad novou kompletní nahrávkou Dvořákových symfonií. O vzniku skladeb i jejich natáčení Českou filharmonií a Jiřím Bělohlávkem. Český rozhlas 2014, 10. 9. Available online

ACHENBACH, Andrew: Dvořák Cello Concerto. Gramophone 2014, 22. 4. Available online

WIGMAN, Brian: Antonín Dvořák. Complete Symphonies & Concertos. Classical.net 2014. Available online

SMACZNY, Jan: Dvořák’s Symphonies Nos 1-9 performed by the Czech Philharmonic, conducted by Jiří Bělohlávek. ClassicalMusic 2017, 14. 3. Available online

KLEPAL, Boris: Bělohlávkova nahrávka s Českou filharmonií: Stabat Mater interpretoval, jako by ji Dvořák napsal pro něj. iHned 2017, 28. 6. Available online

VÍTEK, Bohuslav: Antonín Dvořák Slovanské tance. Harmonie 2017, č. 2, s. 63.

REITTEREROVÁ, Vlasta: Nová vídeňská Rusalka – promyšlená linie. Opera Plus 2014, 11. 2. Available online